Note: This novel was WINNER of the Booker Prize in 2005.

“My life seemed to be passing before me, not in a flash as it is said to do for those about to drown, but in a sort of leisurely convulsion, emptying itself of its secrets and its quotidian mysteries in preparation for the moment when I must step into the black boat on the shadowed river with the coin of passage cold in my already coldening hand.”

Boo ker Prize-winning author John Banville presents a sensitive and remarkably complete character study of Max Morden, an art critic/writer from Ireland whose wife has just died from a lingering illness. Seeking solace, Max has checked into the Cedars, a now dilapidated guest-house in the seaside village of Ballyless, where he and his family had spent summers when he was a child. In those days Max had spent hours in the company of the Graces, a wealthy family whose children, twins Chloe and Myles, became his constant companions. Images of foreboding suggest that some tragedy occurred while he was there, though the reader discovers only gradually what it might have been. Now renting a room at the Cedars for an indefinite stay, Max broods about the nature of life, love, and death, relives earlier times, and tries to reconcile his memories, some of which are incomplete and imperfect, with the reality of his present, sad life.

ker Prize-winning author John Banville presents a sensitive and remarkably complete character study of Max Morden, an art critic/writer from Ireland whose wife has just died from a lingering illness. Seeking solace, Max has checked into the Cedars, a now dilapidated guest-house in the seaside village of Ballyless, where he and his family had spent summers when he was a child. In those days Max had spent hours in the company of the Graces, a wealthy family whose children, twins Chloe and Myles, became his constant companions. Images of foreboding suggest that some tragedy occurred while he was there, though the reader discovers only gradually what it might have been. Now renting a room at the Cedars for an indefinite stay, Max broods about the nature of life, love, and death, relives earlier times, and tries to reconcile his memories, some of which are incomplete and imperfect, with the reality of his present, sad life.

As Max probes his memories, he reveals his state of mind and most intimate feelings, constantly questioning the accuracy of his memory, and juxtaposing his distant memories of Ballyless with his recent memories in which his wife Anna’s “inappropriate” illness was diagnosed and her futile  treatments begun. Through flashbacks, he also introduces us to his earlier married life with Anna and his fervent hopes that through her he could become someone more interesting. “I was always a distinct no-one, whose fiercest wish was to be an indistinct someone,” he says, confessing that he saw her as “the fairground mirror in which all my distortions would be made straight.”

treatments begun. Through flashbacks, he also introduces us to his earlier married life with Anna and his fervent hopes that through her he could become someone more interesting. “I was always a distinct no-one, whose fiercest wish was to be an indistinct someone,” he says, confessing that he saw her as “the fairground mirror in which all my distortions would be made straight.”

At the Cedars, his companion now is not the Graces but a pathetic “colonel” from Belfast, a dull, little man trying to woo Miss Vavasour, the manager. Max, desiring solitude but feeling lonely, looks for solace in alcohol and in trips to the pub, occasionally with the colonel, but he is at loose ends, spending much time contemplating philosophical questions. “The past, I mean the real past,” he says, “matters less than we pretend,” and he admits that for him, “Being here [at the Cedars] is just a way of not being anywhere.” Finding no solace or satisfaction from philosophy or religion, he comments that “Given the world that he created, it would be an impiety against God to believe in him.”

A real “Tiepolo sky,” from “An Allegory with Venus and Time”

As his stay lengthens, he begins to worry that “I am becoming my own ghost,” but he continues to think about Chloe, his first love (after he abandoned his crush on her mother) and about Myles, her mute twin, as the three of them practiced swimming, explored sexuality and love, and tried to figure out the world as they saw it. He muses about Anna, his wife, in whom “I had my first experience of the absolute otherness of other people,” but he also notes that these people vanish from memory and cannot be recalled with clarity when they are out of sight, and he comes to no important recognition of memory as a soothing force in his life.

More a meditation than a novel with a strong plot, The Sea brings Max to life (as limited as his life is), recreating his seemingly simple, yet often profound, thoughts in language which will startle the reader into recognition of their universality. To some extent an everyman, Max speaks to the reader in uniquely intimate ways. In breathtaking language, filled with emotional connotations, he captures nature in perfect images, e. g., drawing parallels between broken eggs in a bird’s nest when he was a child, and Anna in her illness, “as full and frail as an ostrich egg.” As an art lover, he also interprets life through art–“a Tiepolo sky,” a hair-washing scene reminiscent of Duccio and Picasso, a death scene similar to something by Gericault and de la Tour. He objectifies his thoughts about memory through Pierre Bonnard’s many portraits of “Nude in the Bath,” paintings of Bonnard’s wife in which she remains a young girl, even when she is seventy years old. Images of the bath and the sea pervade the novel–cleansing, combined with the ebb and flow of life.

One of Bonnard’s “Nude in the Bath” series

An ordinary man in his late fifties or early sixties engaging in interior battles with personal demons may not appeal to readers who prefer snappy dialogue and action plots. But other readers, especially those who may have faced the deaths of family or friends and recognized the limitations of memory, may recognize in Max a kindred spirit. I have rarely read such a short book so slowly—or reread with pleasure so many passages of extraordinary beauty and import—and I felt a connection with Max that I have never felt before in any of Banville’s previous novels. Intimate and personal, this is one of the few books that I have immediately re-read upon completing it. (On my All-Time Favorites List)

ALSO by John Banville: THE UNTOUCHABLE, THE INFINITIES, ANCIENT LIGHT, SHROUD, APRIL IN SPAIN

Many of. John Banville’s mysteries are written under the pen name of Benjamin Black. Those are listed in the ‘Titles” section under the name of Benjamin Black.

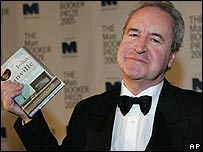

Notes: The author’s photo at the Booker Prize ceremony is from http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/entertainment/4319734.stm at the National Gallery in London: http://www.nationalgallery.org.uk

One of the Bonnard “Nude in the Bath” series: http://www.usc.edu/schools/annenberg/asc/projects/comm544/library/images/749.html