Note: Kate Atkinson was WINNER of the Whitbread Book of the Year Award for her first novel, Behind the Scenes at the Museum (1995), and was WINNER of the Costa Award, its renamed successor, for this novel.

“It was certainly true that [Ursula] often felt confused between what was real and what was not. And the terrible fear – fearful terror – that she carried around inside her. The dark landscape within…And sometimes, too, she knew what someone was about to say before they said it or what mundane incident was about to occur…the second sight.”

Wildly imaginative, and filled with scenes so vivid that the reader cannot help but participate in the story as it unwinds, Life After Life engages the reader from the outset with the novel’s seemingly contradictory premises: first, that everything is real and nothing is real; and second, that everything changes and nothing changes. Irony rules. As the book’s title confirms, this is a novel in which there is a life after life: A character’s fate is revealed in the novel in one place but is then revisited and rewritten in new scenes later in the novel, creating a new fate or fates. The characters change as they move forward obliquely, learning from each set of new, changed circumstances as reality merges with fantasy to create a new reality in a new dimension. To bring these themes to life (and give them new vitality), the author creates a unique structure. The dates of the various chapters jump around between 1910 and 1967, and more strikingly, one chapter, “Snow,” appears eleven times with the same date – February 11, 1910 – throughout the book. Each “Snow” chapter contains the same basic situation, the birth of a baby, involving the same characters, yet the described events have different, sometimes contradictory, outcomes. Five chapters named “Armistice” all occur on Nov. 11, 1918, the end of World War I, and like the “Snow” chapters, present the same characters but, once again, provide new and different angles to the story and its outcomes.

Wildly imaginative, and filled with scenes so vivid that the reader cannot help but participate in the story as it unwinds, Life After Life engages the reader from the outset with the novel’s seemingly contradictory premises: first, that everything is real and nothing is real; and second, that everything changes and nothing changes. Irony rules. As the book’s title confirms, this is a novel in which there is a life after life: A character’s fate is revealed in the novel in one place but is then revisited and rewritten in new scenes later in the novel, creating a new fate or fates. The characters change as they move forward obliquely, learning from each set of new, changed circumstances as reality merges with fantasy to create a new reality in a new dimension. To bring these themes to life (and give them new vitality), the author creates a unique structure. The dates of the various chapters jump around between 1910 and 1967, and more strikingly, one chapter, “Snow,” appears eleven times with the same date – February 11, 1910 – throughout the book. Each “Snow” chapter contains the same basic situation, the birth of a baby, involving the same characters, yet the described events have different, sometimes contradictory, outcomes. Five chapters named “Armistice” all occur on Nov. 11, 1918, the end of World War I, and like the “Snow” chapters, present the same characters but, once again, provide new and different angles to the story and its outcomes.

The book is loads of fun, speeding along on the strength of the author’s deft handling of details and her creation of lively characters who interest us as their circumstances change – moving us, sometimes, from grief to happiness or from delight to puzzlement. This characteristic may be seen specifically in the first three chapters, which cover only twelve pages, the highlight of which is young woman, identified only by her initials, “UBT,” who is able to get physically close enough to Adolf Hitler to fire one shot. Through flashback in the second chapter, the reader learns that this mysterious “UBT” was named Ursula Todd, but she was born during a snowstorm in the English countryside and strangled on her own umbilical cord. In the third chapter, however, Dr. Fellowes arrives in the nick of time to save the baby, and it is from this moment on that the reader begins wondering how many death-defying encounters Ursula (“UBT”) will have, and how she will end up so close to Hitler just twenty years later. Atkinson brilliantly creates and then recreates all the characters of this family.

People, including Ursula, sometimes die again and again, only to have their stories revised to save them, a technique which allows Atkinson to show simultaneously the sudden shifts of fate that can mean life or death (one of her main themes) and also to develop the effects on characters (and readers) which these opposing outcomes have, a unique way to broaden the scope of the novel while retaining the same characters.

People, including Ursula, sometimes die again and again, only to have their stories revised to save them, a technique which allows Atkinson to show simultaneously the sudden shifts of fate that can mean life or death (one of her main themes) and also to develop the effects on characters (and readers) which these opposing outcomes have, a unique way to broaden the scope of the novel while retaining the same characters.

On the historical level, of course, one cannot change the dates and events of World War I and World War II, both of which are described in detail here. Atkinson’s focus on the local level (i.e., which buildings, among many, get blown up during the Blitz, which fictional characters die, and which have their stories revised so they can come back to life) does show, however, that the different outcomes on the local level expand one’s ove rall understanding of these larger disasters. The reader empathizes with the repeating characters, celebrates their lives, rejoices when, against odds, they cheat death in a retold tale, and understands the kaleidoscope of events and emotions which big events and big wars create.

rall understanding of these larger disasters. The reader empathizes with the repeating characters, celebrates their lives, rejoices when, against odds, they cheat death in a retold tale, and understands the kaleidoscope of events and emotions which big events and big wars create.

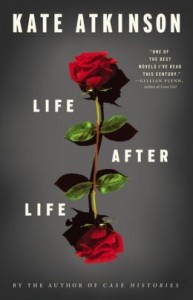

In a remarkable twist, the book’s brilliant cover design by Keith Hayes (for the US edition) graphically illustrates the unusual action and themes. Both the front and back covers feature the same graphics – dominated by a red rose (which looks real) but which, surprisingly, has red blossoms at both ends of a single stem (decidedly unreal), floating on its own, free of roots and earth, looking completely natural through its unreality. Life and death (and life again); love and hate (and violence); reality and imagination (and the revisions of history); facts and memories (and dreams), all combine in this cyclical, often hypnotic rendering of big ideas interpreted in unique ways. In straddling the line between the natural and supernatural, the normal and the paranormal, Kate Atkinson expands the scope and impact of Life After Life, providing new insights into historical events, and creating the most absorbing novel I have read all year, one which blurs the line between fact and fiction itself.

ALSO by Kate Atkinson: CASE HISTORIES (Brodie #1), ONE GOOD TURN (#2), WHEN WILL THERE BE GOOD NEWS (#3), STARTED EARLY, TOOK MY DOG (#4), BIG SKY (#5)

ALSO by Kate Atkinson: CASE HISTORIES (Brodie #1), ONE GOOD TURN (#2), WHEN WILL THERE BE GOOD NEWS (#3), STARTED EARLY, TOOK MY DOG (#4), BIG SKY (#5)

Photos, in order: The author’s photo appears in http://www.telegraph.co.uk

Adolf Hitler and Eva Braun are shown here: http://zeegrooves.blogspot.com

The Daily Mail shows this iconic photo (by Herbert Mason) of St. Paul’s, standing amidst surrounding damage, on its front page:

http://coolphotographypics.blogspot.com

The damage in the dome of St Paul’s, which occurred on Dec. 29, 1940, is from http://www.allposters.com