“Make a home for yourself in your carefree days. They’re dreams, but you don’t have to wake up yet. Ten years and you’ll start to wake up, five more and you’ll struggle against the awakening, ten more years and you’ll be content with what you have. It’s not a bad thing, far from a misfortune. In fact, it’s a new form of happiness, and you’ll cherish it like all your other happy feelings.”

Elsa Ahlqvist is dying, something she learned only six months ago. A seventy-year-old psychologist married for fifty years to Martti, a well-known artist, Elsa is being attended at home by her physician daughter Eleonoora (Ella) and her granddaughters, Anna and Maria. As each member of the family reacts to Elsa’s declining health, the entire family dynamic unfolds. Martti, for example, is sad about his accomplished daughter’s adult persona, that of a meticulous woman with an “almost expressionless determination on her face,” and he thinks, not for the first time, that “this woman [Eleonoora] had stolen his daughter from him, she was hiding the pigtailed, smiling Ella somewhere deep within her pragmatism. If Martti could just find some magic word from her childhood years, and say it, Eleonoora would be Ella again, jumping up and down in the doorway…”

Elsa Ahlqvist is dying, something she learned only six months ago. A seventy-year-old psychologist married for fifty years to Martti, a well-known artist, Elsa is being attended at home by her physician daughter Eleonoora (Ella) and her granddaughters, Anna and Maria. As each member of the family reacts to Elsa’s declining health, the entire family dynamic unfolds. Martti, for example, is sad about his accomplished daughter’s adult persona, that of a meticulous woman with an “almost expressionless determination on her face,” and he thinks, not for the first time, that “this woman [Eleonoora] had stolen his daughter from him, she was hiding the pigtailed, smiling Ella somewhere deep within her pragmatism. If Martti could just find some magic word from her childhood years, and say it, Eleonoora would be Ella again, jumping up and down in the doorway…”

Martti himself has never seemed to find the “right” medium for his artwork, choosing to be an avante-garde experimenter, and now, in retirement, he does little painting. His inspiration seems to have vanished, though it sometimes appears to him as a woman in a dream. Anna, the older granddaughter, has had a breakdown, the result of a love affair that has ended. She has been devastated more by the loss of her relationship with her lover’s young daughter, whom she loved as her own, than by the man himself. As for Elsa, she tries to remain upbeat, having a huge family Christmas celebration immediately after the diagnosis, and refusing to stay in the hospital when she is weak and near death six months later.

As the family surrounds Elsa with love in her final weeks, Elsa tries to keep the mood light, recreating the past and its happy memories. On one of Anna’s days with her grandmother, she remembers playing with the doll house and her mother’s old doll and dreaming about a magical future quite different from what she has experienced. When her grandmother playfully suggests that they play “dress up,” as they once did, Anna goes to the closet and discovers, not the dress she used to wear when she pretended to be “Bianca from Italy,” but one which she has never seen. Anna soon learns that it belonged to Eeva, a stranger to her.

As the family surrounds Elsa with love in her final weeks, Elsa tries to keep the mood light, recreating the past and its happy memories. On one of Anna’s days with her grandmother, she remembers playing with the doll house and her mother’s old doll and dreaming about a magical future quite different from what she has experienced. When her grandmother playfully suggests that they play “dress up,” as they once did, Anna goes to the closet and discovers, not the dress she used to wear when she pretended to be “Bianca from Italy,” but one which she has never seen. Anna soon learns that it belonged to Eeva, a stranger to her.

As most readers will have figured out, by this time, Eeva once lived in the house with Elsa, Martti, and Eleonoora, working as Eleonoora’s nanny for several years. Her effect on the individual members of the family was as life-changing for them as it was for her. Now, in Elsa’s last days, the story of Eeva emerges, some family members knowing it but having put it aside for many years, and others not even guessing it. It is Anna, the granddaughter, who pursues Eeva’s story, perhaps because she sees similarities between Eeva and herself. She wants the whole story, the “true” story, in terms of its several meanings – correct, straight, honest, and real.

Seurasaari Beach

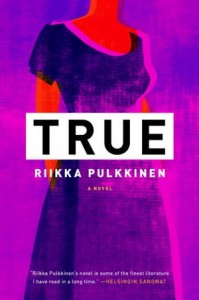

Finnish author Riikka Pulkkinen’s novel True uses multiple points of view and a time frame that shifts from the early 1960s to the present, as Martti, Elsa, Eleonoora, and Eeva share their memories of the more than three years in which they lived together. The nature of the relationships and the effects each has had on the others, continuing into the third generation through Eleonoora’s daughter Anna, are explored in elaborate psychological detail, making the external setting in Finland, as opposed to any other western country, virtually irrelevant. The characters’ behavior and emotional reactions are explored with sensitivity, but since the story is told in retrospect, Eeva’s long term effects on the main characters’ lives are obvious to the reader from the beginning. There are surprises, however, as the relationships with Eeva unfold, and lovers of psychological novels will not be disappointed.

Kiosk at Esplanadi Park

The author takes the novel beyond the specifics of this family and into the universal by including many aphorisms and sometimes ponderous insights throughout the novel. Eleonoora comments that “The living know nothing of death, but dying, its stealthy inevitability, comes into the lives of the living. Time slows, reality is given walls of grief within which the dying and those who accompany them perform their rituals of devotion.” Anna remarks that “Relationships between people are like dense forests. Or maybe it’s the people themselves who are forests, trail after trail opening up within them, trails that are kept hidden from others…” Eeva herself believes that “There are those of us who are content with the beginnings of sentences and the call of a loon as it rakes across the surface of the lake…Somewhere else, the jungle is bathed in napalm and a lot of people are upset about it.” Martti believes that “Your love is only yours…It’s not your prison, and it isn’t preventing you from being free.” As for Elsa, she tells Anna that “An apology is a request to be seen as you are, in spite of what you’ve done. Responding to [an apology] is the deepest love a person is capable of.”

Those who prefer more subtle revelations of theme may tire of these personal pronouncements about the world, while others will find them helpful in expanding the focus on this family and the characters. My own biggest question lies at the heart of the novel: The story of Eeva took place more than forty years ago, and Elsa is a respected psychologist. Though she may believe that her granddaughter Anna has much in common with Eeva, it is difficult to imagine why she would, many years later, feel compelled to share Eeva’s story, which intimately affects other family members and not just herself. She knows how vulnerable Anna is, yet takes a chance with her future life, possibly telling her more than she wants or needs to know. Even though this is a novel and not reality, of course, it is presented as “true,” and I could not get past the feeling that in real life the sharing of this story would have been regarded as a violation of privacy from which some family members, including Anna herself, might not have benefited as much as Elsa thinks they would – not a legacy that most people would want to leave behind.

Those who prefer more subtle revelations of theme may tire of these personal pronouncements about the world, while others will find them helpful in expanding the focus on this family and the characters. My own biggest question lies at the heart of the novel: The story of Eeva took place more than forty years ago, and Elsa is a respected psychologist. Though she may believe that her granddaughter Anna has much in common with Eeva, it is difficult to imagine why she would, many years later, feel compelled to share Eeva’s story, which intimately affects other family members and not just herself. She knows how vulnerable Anna is, yet takes a chance with her future life, possibly telling her more than she wants or needs to know. Even though this is a novel and not reality, of course, it is presented as “true,” and I could not get past the feeling that in real life the sharing of this story would have been regarded as a violation of privacy from which some family members, including Anna herself, might not have benefited as much as Elsa thinks they would – not a legacy that most people would want to leave behind.

An interview with the author appears here: http://www.france24.com The interview starts at about the 7:30 mark.

Photos, in order: The author’s photo by Kuva Katja Losonen is from http://www.oululehti.fi

At one point, when the weather is chilly, Elsa decides she wants to go for a swim at Seurasaari Beach, pictured on http://pictures.traveladventures.org

Anna meets a friend at Esplanadi Park and goes to this charming kiosk for a snack. http://looky.wordpress.com

The map of Finland, from http://www.lonelyplanet.com, shows Helsinki on the southernmost tip of the peninsula and Kuhmo, the small town where Eeva comes from, in the middle of the eastern border, next to Russia.