“It wasn’t just an exercise. Time travel, I decided, cried out to become a regular pastime. I should campaign for it. ‘Infinitely more liberating,’ I would call from the rooftops, ‘than all this nonsense about the burning of your bras!’ ”

I cannot claim to be one of the people that author Stephen Benatar has greeted at London bookstores and persuaded to read one of his novels, though his career-long commitment to the self-publishing and self-publicizing of his books has certainly made him many friends and earned him many readers. Instead, halfway around the world, I received this book from an astute British friend, who knows how much I enjoy the dark British comedies written in the 1980s by writers like Jane Gardam, Alice Thomas Ellis, Molly Keane, Muriel Spark, and Barbara Pym. These authors, however, were fortunate to have found major publishers who brought their often-satiric, sometimes twisted little comedies about odd characters to public attention, wide acclaim, and significant sales. Stephen Benatar, whose work is certainly the equal of these other writers, received wide acclaim and prize nominations when his first two novels (including this one, his second) were published in the early 1980s. His books did not catch on with the public, however, and for the past thirty years, he has been self-publishing and hand-selling his books in bookshops around London, where he purportedly sells fifty to a hundred books at each weekend reading. With the recent re-publication of this novel by the New York Review of Books in 2010, Benatar, now seventy-three, may finally be on the road to finding the audience he has worked so hard for, and the screen rights for this novel have recently been sold.

I cannot claim to be one of the people that author Stephen Benatar has greeted at London bookstores and persuaded to read one of his novels, though his career-long commitment to the self-publishing and self-publicizing of his books has certainly made him many friends and earned him many readers. Instead, halfway around the world, I received this book from an astute British friend, who knows how much I enjoy the dark British comedies written in the 1980s by writers like Jane Gardam, Alice Thomas Ellis, Molly Keane, Muriel Spark, and Barbara Pym. These authors, however, were fortunate to have found major publishers who brought their often-satiric, sometimes twisted little comedies about odd characters to public attention, wide acclaim, and significant sales. Stephen Benatar, whose work is certainly the equal of these other writers, received wide acclaim and prize nominations when his first two novels (including this one, his second) were published in the early 1980s. His books did not catch on with the public, however, and for the past thirty years, he has been self-publishing and hand-selling his books in bookshops around London, where he purportedly sells fifty to a hundred books at each weekend reading. With the recent re-publication of this novel by the New York Review of Books in 2010, Benatar, now seventy-three, may finally be on the road to finding the audience he has worked so hard for, and the screen rights for this novel have recently been sold.  Nominated for the Booker Prize in 1982, when it was first published in London, Wish Her Safe at Home is a startling novel with an even more startling main character, Rachel Waring, a forty-seven-year-old woman who has a dead end job, a cynical roommate, and no friends. Brought up by an overbearing mother whose sense of “correct behavior” seems to have ruined any chances Rachel might have had for a happy life, she is lonely and repressed, with absolutely no understanding of how to meet and make connections with strangers. On one occasion on a train, she tries to open a conversation with a man reading in the seat across from her: “Do you mind if I talk to you for a moment? I’ve just read the most frightful description of a hanging, drawing, and quartering, and I’m afraid I can’t stop reliving it.” At a christening, later in the book, she begins chatting with an attractive young man by asking, out of the blue, “If this were an invasion of the body snatchers, would you be one of the bodies or one of the snatchers?”

Nominated for the Booker Prize in 1982, when it was first published in London, Wish Her Safe at Home is a startling novel with an even more startling main character, Rachel Waring, a forty-seven-year-old woman who has a dead end job, a cynical roommate, and no friends. Brought up by an overbearing mother whose sense of “correct behavior” seems to have ruined any chances Rachel might have had for a happy life, she is lonely and repressed, with absolutely no understanding of how to meet and make connections with strangers. On one occasion on a train, she tries to open a conversation with a man reading in the seat across from her: “Do you mind if I talk to you for a moment? I’ve just read the most frightful description of a hanging, drawing, and quartering, and I’m afraid I can’t stop reliving it.” At a christening, later in the book, she begins chatting with an attractive young man by asking, out of the blue, “If this were an invasion of the body snatchers, would you be one of the bodies or one of the snatchers?”  Benatar wisely lets Rachel tell her own story, creating a classic novel in which the reader identifies with Rachel because she is so pathetic and earnest about her needs and disappointments, at the same time that it is impossible not to recognize how far from “ordinary” Rachel really is in her thinking. Every event here is filtered through Rachel’s own mind, and when she becomes the sole beneficiary of her elderly Aunt Alicia’s Georgian home in Bristol, she decides to leave London, asserting: “Bristol was going to treat me well, provide me with a new start.” Once ensconced in the old house, which she refurbishes and refurnishes, she becomes a “new woman,” buying a red dress, flirting with the vicar, revealing vivid sexual fantasies about the handsome young man who works in her garden, and spending lavishly from her savings on things that make her happy. It is not long before the reader realizes that Rachel has serious emotional problems, even as Rachel herself is finding a kind of happiness that she has never known before. As she reminisces about her past and the man with whom she was desperately in love at age twenty-two, her behavior becomes more understandable, though no less bizarre. Her research on the original builder of the house, Horatio Gavin, an idealistic “champion of the underprivileged” and an associate of William Wilberforce (who led the movement to abolish England’s slave trade), becomes so intriguing to her that she decides to write a book about him, and soon she is imagining herself as “an eighteenth-century Rachel” who soothes the broken heart of Horatio Gavin, whose fiancée has died. “Sometimes,” she says, “I felt utterly convinced I had been singled out for glory.”

Benatar wisely lets Rachel tell her own story, creating a classic novel in which the reader identifies with Rachel because she is so pathetic and earnest about her needs and disappointments, at the same time that it is impossible not to recognize how far from “ordinary” Rachel really is in her thinking. Every event here is filtered through Rachel’s own mind, and when she becomes the sole beneficiary of her elderly Aunt Alicia’s Georgian home in Bristol, she decides to leave London, asserting: “Bristol was going to treat me well, provide me with a new start.” Once ensconced in the old house, which she refurbishes and refurnishes, she becomes a “new woman,” buying a red dress, flirting with the vicar, revealing vivid sexual fantasies about the handsome young man who works in her garden, and spending lavishly from her savings on things that make her happy. It is not long before the reader realizes that Rachel has serious emotional problems, even as Rachel herself is finding a kind of happiness that she has never known before. As she reminisces about her past and the man with whom she was desperately in love at age twenty-two, her behavior becomes more understandable, though no less bizarre. Her research on the original builder of the house, Horatio Gavin, an idealistic “champion of the underprivileged” and an associate of William Wilberforce (who led the movement to abolish England’s slave trade), becomes so intriguing to her that she decides to write a book about him, and soon she is imagining herself as “an eighteenth-century Rachel” who soothes the broken heart of Horatio Gavin, whose fiancée has died. “Sometimes,” she says, “I felt utterly convinced I had been singled out for glory.”  Throughout the novel, Rachel sings songs from the past—“If Love Were All,” “Dancing in the Dark,” “Oh, You Beautiful Doll,” and many others, whose romantic lyrics are quoted. She also remembers the dramatic impression she once made on friends twenty-five years ago when she recited Tennyson’s tragic ballad “The Lady of Shalott.” The interjection of these songs and memories provides further entrée into Rachel’s psyche and her deterioration. As her voice becomes increasingly confidential and revelatory, the involved reader will recognize with alarm the growing contrast between Rachel as she sees herself and Rachel as she appears to the rest of the world. This contrast, which Benatar enhances by never intruding upon Rachel’s frayed psyche, provides the drama and emotional connection which good fiction requires. The reader, inevitably drawn into Rachel’s life, cannot help but be moved by Rachel’s story, even as s/he sees its sad absurdities, its ironies, and its dark humor.

Throughout the novel, Rachel sings songs from the past—“If Love Were All,” “Dancing in the Dark,” “Oh, You Beautiful Doll,” and many others, whose romantic lyrics are quoted. She also remembers the dramatic impression she once made on friends twenty-five years ago when she recited Tennyson’s tragic ballad “The Lady of Shalott.” The interjection of these songs and memories provides further entrée into Rachel’s psyche and her deterioration. As her voice becomes increasingly confidential and revelatory, the involved reader will recognize with alarm the growing contrast between Rachel as she sees herself and Rachel as she appears to the rest of the world. This contrast, which Benatar enhances by never intruding upon Rachel’s frayed psyche, provides the drama and emotional connection which good fiction requires. The reader, inevitably drawn into Rachel’s life, cannot help but be moved by Rachel’s story, even as s/he sees its sad absurdities, its ironies, and its dark humor.

Also by Stephen Benatar, WHEN I WAS OTHERWISE

Photos, in order: The author’s photo and a fascinating feature story about Stephen Benatar appear on http://www.express.co.uk

The most famous house in Bristol (pictured here), a Georgian house built by John Pinney, may have been the model for the house in this novel: http://www.bristol.gov.uk

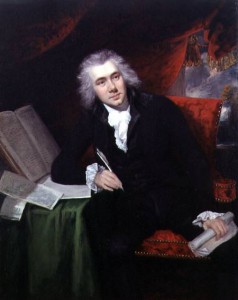

William Wilberforce, age twenty-nine in this portrait, is said to have been an associate of Horatio Gavin, who was thirty-two in this story. The painting is by John Rising. http://en.wikipedia.org

In this video from Carnegie Hall in 1961, Judy Garland sings “If Love Were All,” the song beloved of Rachel’s Aunt Alicia, which appears on the first page of this novel: