Note: William Kennedy was WINNER of both the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Critics Circle Award for IRONWEED in 1984. In 2009, he was WINNER of the O’Neill Award for Lifetime Achievement.

“Hemingway: What are you writing?

Quinn: Grim stories about political exiles in Miami buying guns to send to Cuba. The grimness is redeemed by my simple declarative sentences.

Hemingway: Remove the colon and semicolon keys from your typewriter. Shun adverbs, strenuously.”

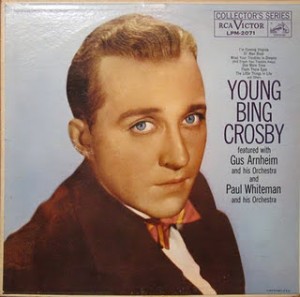

William Kennedy’s latest novel in the Albany Cycle, his eighth, continues the story of several families from Albany, New York, during the heyday of its infamous, politically corrupt “machine.” Focusing on Daniel Quinn, a newspaper reporter who is the grandson of the Daniel Quinn who reported on the Civil War in Quinn’s Book, and son of the now-senile George, a “hail-fellow-well-met” charmer with connections to seemingly everyone in Albany, this novel begins in August, 1936, when Daniel is a child. Peering over the banister of the front staircase in Mayor Alex Fitzgibbon’s house, Daniel sits quietly watching as his father brings a piano (origins unknown) into the Mayor’s house. Cody Mason, a pianist specializing in Harlem “stride,” is about to put on a private show with the young Bing Crosby. Daniel Quinn is overcome by the passion of this music.

William Kennedy’s latest novel in the Albany Cycle, his eighth, continues the story of several families from Albany, New York, during the heyday of its infamous, politically corrupt “machine.” Focusing on Daniel Quinn, a newspaper reporter who is the grandson of the Daniel Quinn who reported on the Civil War in Quinn’s Book, and son of the now-senile George, a “hail-fellow-well-met” charmer with connections to seemingly everyone in Albany, this novel begins in August, 1936, when Daniel is a child. Peering over the banister of the front staircase in Mayor Alex Fitzgibbon’s house, Daniel sits quietly watching as his father brings a piano (origins unknown) into the Mayor’s house. Cody Mason, a pianist specializing in Harlem “stride,” is about to put on a private show with the young Bing Crosby. Daniel Quinn is overcome by the passion of this music.

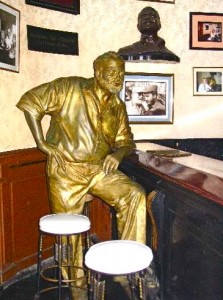

Only six pages (and twenty-one years) later, Quinn, an experienced reporter, is in Havana in March, 1957, hanging out at the El Floridita bar and hoping that its most famous patron, Ernest Hemingway, will show up. Quinn has just quit his job at the Miami Herald, and is working on a novel, he says, but before Hemingway appears, Quinn meets and falls hopelessly in love with Renata Suarez Otero, a secret supporter of Castro’s revolution and a gunrunner determined to outst Fulgencio Batista from power. Renata and many of Castro’s other supporters believe in Santeria and in the power of Chango, the warrior king of kings venerated by traditional Cubans, and she is so committed and so passionate about what she is doing that she is described as being “from another dimension, perhaps life itself, equally ready for life or death.”

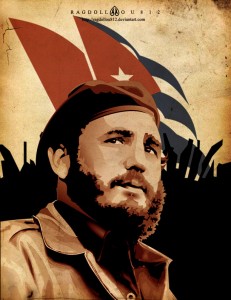

These two opening scenes, the arrival of Hemingway, his boorish attack on a tourist, and Quinn’s interview with the young Fidel Castro establish the narrative tone and atmosphere for this novel, which focuses on two revolutions, the Castro-led revolution in Cuba and the slightly later revolution in the US in the 1960s regarding civil rights. Using the life of Tremont Van Ort, a black pool hustler with two-tone shoes, as a point of focus for the Albany “revolution,” the author concentrates the action on June 5, 1968, the day that Robert Kennedy is shot. That day a race riot breaks out in Albany: “This was not your ordinary race riot, but a spontaneous exercise in anarchy, the aim being not reciprocal death among racial antagonists but multicolored and miscegenational chaos.”

The chaos of the race riot parallels in many ways the seeming chaos of much of the narrative. Though Kennedy is much too good a writer to lose sight of his thematic focus completely, the many characters, the often complex backstories of each, the unexpected shifts in time through generations, and even Quinn’s dreams make the story line difficult to absorb, at times. In addition, some of the most important explanations for what is happening are deliberately withheld until nearly the end of the novel.

The novel, however, has many scenes of wit and charm, and even more which are full of power. The local color with which William Kennedy imbues settings in both Cuba and Albany keeps the reader enthralled and reading onward, even when almost overwhelmed with questions about the action. Quinn visits the Hotel Nacional and Montmartre casino, owned by Meyer Lansky, and the Sans Souci, owned by Santo Traffican te. He is warned about the dangers to himself because of his associations with Renata, and he accepts the red and white “Chango beads” given to him by Narciso, an aged Santeria priest. He travels to Santiago and into the Cuban Sierra, and he observes the atrocities committed by Batista’s army. Throughout, Quinn believes himself to be following in the footsteps of his grandfather, also named Daniel, who was fascinated by Carlos Manuel de Cespedes, a Cuban planter who freed his slaves in 1868 and fought a ten year war against the Spanish in Cuba. He imagines himself writing a future novel about Castro, similar to the book which his grandfather wrote about Cespedes and the Mambi.

te. He is warned about the dangers to himself because of his associations with Renata, and he accepts the red and white “Chango beads” given to him by Narciso, an aged Santeria priest. He travels to Santiago and into the Cuban Sierra, and he observes the atrocities committed by Batista’s army. Throughout, Quinn believes himself to be following in the footsteps of his grandfather, also named Daniel, who was fascinated by Carlos Manuel de Cespedes, a Cuban planter who freed his slaves in 1868 and fought a ten year war against the Spanish in Cuba. He imagines himself writing a future novel about Castro, similar to the book which his grandfather wrote about Cespedes and the Mambi.

In the Albany sections, which are more emotionally resonant, the author creates some unforgettable characters: Reverend Matthew Daugherty, a Franciscan priest, whose actions in opposition to the Albany political machine have led to his virtual silencing; Quinn’s father George, now senile, who, when driven to the Elks Club to spend the day so Quinn can work, wanders off into an old neighborhood, now completely changed, and tries to relive his memories; Tremont Van Ort, an alcoholic who finds himself sought by a Black Power activist, who wants him to kill the Mayor; and an assortment of prostitutes, drug bosses, and musicians. In this section, like the Cuba section, Quinn also sees himself writing a novel – this one about the race riots, and especially about Tremont. The final seventy-five pages unite the two sections and explain some of the long-lived questions about everything that happened in Cuba when Quinn visited in 1957.

an old neighborhood, now completely changed, and tries to relive his memories; Tremont Van Ort, an alcoholic who finds himself sought by a Black Power activist, who wants him to kill the Mayor; and an assortment of prostitutes, drug bosses, and musicians. In this section, like the Cuba section, Quinn also sees himself writing a novel – this one about the race riots, and especially about Tremont. The final seventy-five pages unite the two sections and explain some of the long-lived questions about everything that happened in Cuba when Quinn visited in 1957.

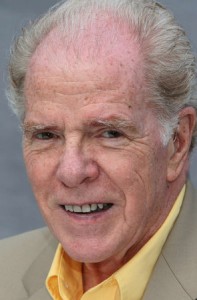

The autobiographical overtones of this novel about revolutions, both social and political, may be partly responsible for the meandering feeling of the narrative. William Kennedy himself, stretching his literary legs after his discharge from the army, lived in Puerto Rico (not Cuba) for a number of years, and he became close friends with the iconoclastic Hunter S. Thompson (not Hemingway). Upon his return to Albany, he was an investigative reporter for the Albany newspaper, exposing the corruption of the local “machine.” A sense of realism, honed by Kennedy’s journalistic career, pervades Chango’s Beads and Two-Tone Shoes, but the novel is also highly literary, filled with repeating images, symbols, dreams, and music to enliven the action and broaden the scope. His humor and irony add considerable warmth to the novel, and for many readers those qualities will more than outweigh the sometimes wooden characters and wandering narrative.

ALSO by William Kennedy: IRONWEED

Photos, in order: The author’s photo appears on http://articles.philly.com

Young Bing Crosby from 1958 is on http://derbingle.blogspot.com

The El Floridita is now home to this bronze version of Ernest Hemingway, lounging at his favorite corner of the bar: http://members.virtualtourist.com The bar sign itself appears on http://twilightlounge.wordpress.com

This 1959 poster of Fidel Castro may be found on http://cille85.wordpress.com

The song “Shine,” sung by Bing Crosby (and the Mills Brothers) echoes and re-echoes throughout the novel. “Konidolfine” has posted the song and some old photos: