“I hear a train’s wheels clicking as it passes through the little station where, a year back, they herded us from the trucks and we began the long straggle up to the camp. I can remember no lonelier sound, nor one that so painfully proclaims the absoluteness of our banishment from a world that each day slips further from us…our bitter Eden, the only solid anchorage under the sun.” – the speaker, contemplating his life in a POW camp.

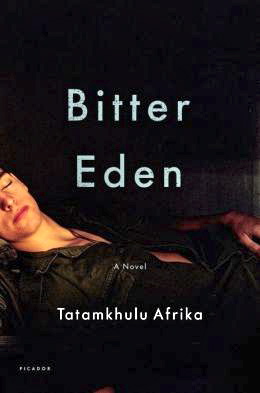

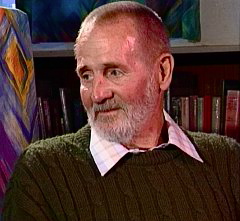

Moments of tenderness alternate with dramatic moments of violence in this semi-autobiographical novel of World War II by Tatamkhulu Afrika, a name assumed by the author late in life and meaning “Grandfather Africa.” Born in 1920 in Egypt, “Tata,” as he calls himself, lost his Egyptian name when his family died shortly after moving to South Africa in the early 1920s. He was adopted by Christian foster parents, friends of his family, and lived with them until the outbreak of World War II, when he left to fight against the Axis powers in the African campaign in Libya. During the Battle of Tobruk, he was captured by the Germans, shipped to a prison camp in Italy, and after the fall of Italy, to Germany’s northeast border. It is the four years of his captivity which become the setting for Bitter Eden, his third book. His first novel, written when he was seventeen and published by a “venerable” publishing house in London, did not survive the Blitz – all but two copies were destroyed when the building was bombed. Much later, he wrote short stories and poetry, but it was not until 2002, sixty-five years after his first novel, that he published his Bitter Eden, which received widespread critical acclaim. He died just two weeks after his book was chosen by critic Mark Simpson of The Independent as one of the best two books of that year.

Moments of tenderness alternate with dramatic moments of violence in this semi-autobiographical novel of World War II by Tatamkhulu Afrika, a name assumed by the author late in life and meaning “Grandfather Africa.” Born in 1920 in Egypt, “Tata,” as he calls himself, lost his Egyptian name when his family died shortly after moving to South Africa in the early 1920s. He was adopted by Christian foster parents, friends of his family, and lived with them until the outbreak of World War II, when he left to fight against the Axis powers in the African campaign in Libya. During the Battle of Tobruk, he was captured by the Germans, shipped to a prison camp in Italy, and after the fall of Italy, to Germany’s northeast border. It is the four years of his captivity which become the setting for Bitter Eden, his third book. His first novel, written when he was seventeen and published by a “venerable” publishing house in London, did not survive the Blitz – all but two copies were destroyed when the building was bombed. Much later, he wrote short stories and poetry, but it was not until 2002, sixty-five years after his first novel, that he published his Bitter Eden, which received widespread critical acclaim. He died just two weeks after his book was chosen by critic Mark Simpson of The Independent as one of the best two books of that year.

As the novel begins, an elderly man is opening two letters which accompany a package. Telling the story from his own point of view, the old man learns in the first letter, from a law firm, that someone the speaker refers to only as “he,” someone he knew more than fifty years ago, has died after a long illness and that the speaker has received a legacy. The second letter is from “him,” a man who has been lost to the speaker for virtually all of his post-war life. The legacy and the letter clearly upset the speaker as he wonders “Am I permitting a phantom a power that belongs to me alone? What relevance do they still have – a war that time has tamed into the damp squib of every other war, [and] a love whose strangeness is best left buried where it lies?” Though he knows he should leave the past buried, he is unable to resist: “I listen for the nightingale that will never sing again, hear only the screaming of an ambulance or a patrol car…and lower my face into the emptiness of my hands.” Even his wife cannot help him with his emotions this time.

What follows is the story of the four years the speaker survived when, during the long siege of Tobruk, he suddenly found himself a prisoner of war. Transported from the battlefield by the Germans, he discovers many other Allied prisoners in the truck to the prison camp. The first person he meets is Douglas Summerfield, who, like the speaker, is from Division Headquarters, a fact that Douglas believes implies some special relationship between them. The speaker, who identifies himself as Tom Smith, is “put off” by Douglas’s movements, “the little almost dancing steps he takes even when, supposedly, he is standing still, the delicate, frenetic gestures of his hands, the almost womanliness of him that threatens to touch – and touch – and touch.” Douglas is also extremely religious, constantly running the rosary through his fingers and muttering prayers under his breath – and constantly looking through the crowd for the friendly face of Tom Smith, like, as Tom sees it, “a drowning clown or a tart desperate for trade.”

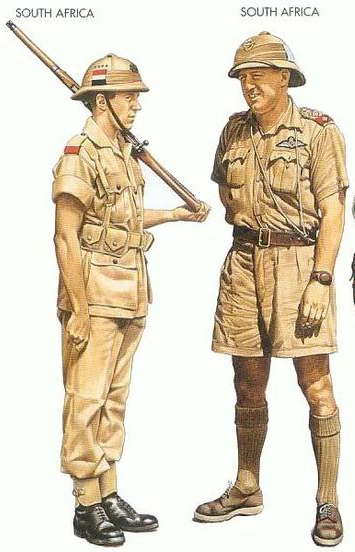

South African forces celebrate the capture of a flag from Italian-held Libya in 1941. Note the uniforms.

Though captured by the Germans, the prisoners are turned over to the Italians, who claim to rule Libya. The horrors of war, the hunger, the forced marches, the crowding, and the refusal of their captors to allow “bathroom breaks” demoralize and frighten the Allied prisoners. One man is trampled to death by others who are propelled forward. Others are shot if they stop walking, as the “Ites” (the Italians) take delight in tormenting their prisoners, stopping along a pool in the hot sun, then shooting anyone who goes into the water. In the Italian-held town through which the prisoners march on their way to the sea, for transport to Italy, residents stone them. Later, jammed into the hull of the ship, all suffering from dysentery, they learn to rely on each other in dealing with the on-going crises. Tom Smith even comes to respect Douglas Summerfield, “a solid and honourable man,” and he eventually sets up a black market business with him, using cigarettes as currency.

As the Italians face defeat, one of the speaker's friends manages to capture and hide two Italian (Beretta) pistols.

Once in their camp in northern Italy, some men, tormented, hungry, lonely, and scared, become attracted to each other and some begin to “share a blanket,” though the author does not go into descriptive detail that would suggest that all these events are necessarily sexual encounters. To keep from going mad, some of the men also create theatricals, and Tom’s social circle broadens beyond that of Douglas to include a former boxer, an artist, and a director/writer. As Red Cross food deliveries become scarcer, however, the men’s emotions become more fragile. The move of the remaining men to Germany, after the fall of Italy, is actually an improvement, at first – they get some food. Eventually, liberation comes, bringing with it thoughts of home, wives, children, and families. For some soldiers, it means leaving their closest, most trusted friends behind – as they return to the UK or Australia, and some like Tom Smith, to South Africa. For many, it means forever hiding the truth about their feelings for their wartime best friends.

German transport truck, like the one that probably transported the speaker and his friends to northeast Germany after Italy's defeat.

With all the physical deprivations regarding food, shelter, and physical warmth, the men create a kind of “Eden,” a place where some basic needs, such as love and comfort, are met, but it is a “bitter Eden,” where misunderstandings and conflict also reign. Seductive behavior among the men is common – and by singling out one person for affection, a love-struck prisoner overtly challenges the group mentality which is necessary for unified action by an army. Simple activities shared with people you like and admire are part of the Eden we see here, but the sharing is fraught with tensions – even violence – and is often accompanied by guilt. As the novel ends, the speaker known as Tom Smith, now elderly, prepares to open the package containing his legacy, one which brings the novel full circle. This is an honest and controlled novel which focuses brilliantly on some of the well-known but less public aspects of prison camp life.

Pbotos, in order: The author’s photo is from http://www.devon.gov.uk/

The South African uniforms may be found here: http://stukasoverstalingrad.blogspot.com

South African forces (note uniforms) celebrate having captured an Italian flag in Libya, where the speaker and his friends are fighting. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/, 1941.

The Beretta pistol used by Italian troops (and captured by one of the speaker’s friends, appears here: http://en.wikipedia.org

The German transport truck which probably brought the speaker and his friends to northeast German, after Italy fell, is featured here: http://ww2db.com/image.php?image_id=8228

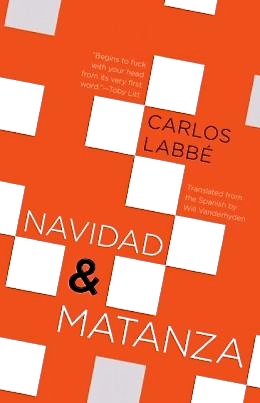

A great deal of fun mixes with nightmare in this surprising and complex novella about writing in general, and about all the permutations of truth vs. fiction, and reality vs. the imagination. The speaker, named Domingo, is participating in a writing experiment/game with six other journalists, named Lunes, Martes, Miercoles, Jueves, Viernes, and Sabado, representing the days of the week, and they are living in a laboratory with limited access. “It’s not even top secret…Rather, to the world, it doesn’t exist. So if for some reason I were to forget my name…I’d die empirically: the possibility of anyone remembering me would die as well.” The seven participants, all among the top students in the Biology Department at the Universidad de Chile, have expressed an interest in discovering “what is beyond science,” and they have volunteered for this writing project. Each participant writes part of a story for others to complete. If the project fails, or if an individual student fails, the organization eliminates that person. At least four, possibly five, of Domingo’s fellow players, have disappeared. “There is only one way to stay alive: make it to the end.”

A great deal of fun mixes with nightmare in this surprising and complex novella about writing in general, and about all the permutations of truth vs. fiction, and reality vs. the imagination. The speaker, named Domingo, is participating in a writing experiment/game with six other journalists, named Lunes, Martes, Miercoles, Jueves, Viernes, and Sabado, representing the days of the week, and they are living in a laboratory with limited access. “It’s not even top secret…Rather, to the world, it doesn’t exist. So if for some reason I were to forget my name…I’d die empirically: the possibility of anyone remembering me would die as well.” The seven participants, all among the top students in the Biology Department at the Universidad de Chile, have expressed an interest in discovering “what is beyond science,” and they have volunteered for this writing project. Each participant writes part of a story for others to complete. If the project fails, or if an individual student fails, the organization eliminates that person. At least four, possibly five, of Domingo’s fellow players, have disappeared. “There is only one way to stay alive: make it to the end.”

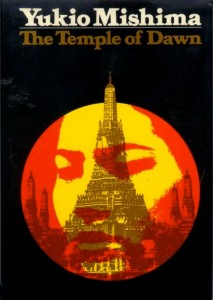

Shigekuni Honda, the main character in this third novel of the Sea of Fertility tetralogy by Yukio Mishima, is forty-six years old in 1940, as the novel opens. He has matured into a successful lawyer and judge in the years since 1912 – 1914, when he was first introduced as the schoolboy friend of Kiyoake Matsugae, the son of a samurai family. Kiyoake, however, died at a young age in

Shigekuni Honda, the main character in this third novel of the Sea of Fertility tetralogy by Yukio Mishima, is forty-six years old in 1940, as the novel opens. He has matured into a successful lawyer and judge in the years since 1912 – 1914, when he was first introduced as the schoolboy friend of Kiyoake Matsugae, the son of a samurai family. Kiyoake, however, died at a young age in

Mai Jia, a popular novelist and winner of the Mao Dun Literature Prize, China’s highest literary honor, writes here under a pen name after serving for seventeen years as a member of the People’s Liberation Army and its intelligence services. Mai’s novel Decoded, originally written and published for a Chinese audience in 2002, and newly translated and published in English, provides a fascinating study of cryptography and its dedicated cryptographers, many of whom give their lives (and even their sanity) to their work. It is also a somewhat difficult book for a western reader, in that many of the traditions of western literature and its standards regarding literary style and structure are not applicable to this novel, which was never written for western readers. Non-Chinese readers need to “go with the flow,” ignoring all preconceptions, both about China and about literature, and immerse themselves in the story, trusting in the lively translation by Olivia Milburn and Christopher Payne, which takes into consideration our unfamiliarity with modern Chinese life and culture. This careful and sensitive translation becomes both revelatory and exciting, providing new insights into worlds that have been closed to most of us, not just the hidden world of the People’s Republic of China and the thinking of many of its people, but also the world of cryptography and the psychological toll it takes on those who dedicate their lives to it.

Mai Jia, a popular novelist and winner of the Mao Dun Literature Prize, China’s highest literary honor, writes here under a pen name after serving for seventeen years as a member of the People’s Liberation Army and its intelligence services. Mai’s novel Decoded, originally written and published for a Chinese audience in 2002, and newly translated and published in English, provides a fascinating study of cryptography and its dedicated cryptographers, many of whom give their lives (and even their sanity) to their work. It is also a somewhat difficult book for a western reader, in that many of the traditions of western literature and its standards regarding literary style and structure are not applicable to this novel, which was never written for western readers. Non-Chinese readers need to “go with the flow,” ignoring all preconceptions, both about China and about literature, and immerse themselves in the story, trusting in the lively translation by Olivia Milburn and Christopher Payne, which takes into consideration our unfamiliarity with modern Chinese life and culture. This careful and sensitive translation becomes both revelatory and exciting, providing new insights into worlds that have been closed to most of us, not just the hidden world of the People’s Republic of China and the thinking of many of its people, but also the world of cryptography and the psychological toll it takes on those who dedicate their lives to it.

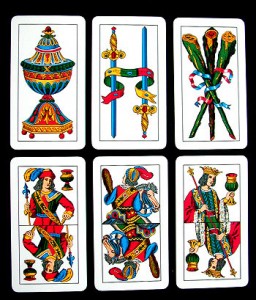

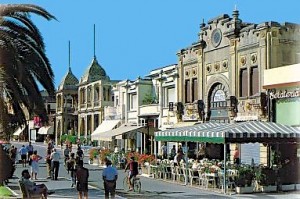

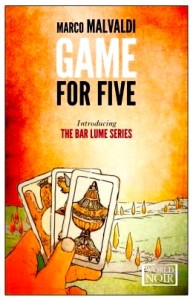

Valuing the idea that “keeping it simple” is important to the success of mystery stories, author Marco Malvaldi draws deliberate parallels between the conclusion in Leonardo Sciascia’s, A Simple Story, in which the main character suddenly finds “where the light switch is,” the clue that allows him to solve the entire mystery, and the final resolution in Malvaldi’s own Game for Five, as bartender Massimo Viviani suddenly solves the murder of a young woman. Simple deductions have been the key to his success. This short, uncomplicated, and often very funny novel depends for its success on more than the mystery itself, however. Quirky characters, three of them in their mid-seventies and one in his eighties, gather regularly at Massimo’s Bar Lume to pass the time playing heated games of briscola and gossiping about everyone and everything in their coastal community outside of Pisa. Massimo, the thirty-ish bartender/owner of the Bar Lume, humors these characters, often joining in their card game as a fifth player when times are slow, and chatting and sharing their lives with them, valuing their commentary on all subjects and offering his own, sometimes contrary, observations to keep things lively.

Valuing the idea that “keeping it simple” is important to the success of mystery stories, author Marco Malvaldi draws deliberate parallels between the conclusion in Leonardo Sciascia’s, A Simple Story, in which the main character suddenly finds “where the light switch is,” the clue that allows him to solve the entire mystery, and the final resolution in Malvaldi’s own Game for Five, as bartender Massimo Viviani suddenly solves the murder of a young woman. Simple deductions have been the key to his success. This short, uncomplicated, and often very funny novel depends for its success on more than the mystery itself, however. Quirky characters, three of them in their mid-seventies and one in his eighties, gather regularly at Massimo’s Bar Lume to pass the time playing heated games of briscola and gossiping about everyone and everything in their coastal community outside of Pisa. Massimo, the thirty-ish bartender/owner of the Bar Lume, humors these characters, often joining in their card game as a fifth player when times are slow, and chatting and sharing their lives with them, valuing their commentary on all subjects and offering his own, sometimes contrary, observations to keep things lively.