“Look at them…Gather ye rosebuds while ye may and all that. It’s the end of Europe, and that’s why they’re dancing, and of course Lisbon is the end of Europe, too. The fingertip of Europe. And everything that Europe is and means is pressed into that fingertip. Too much of it. It’s a cistern full to overflowing…”

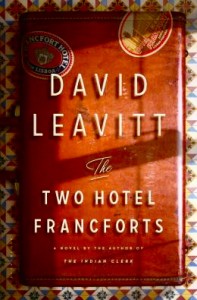

Lisbon, 1940, provides a temporary safe haven and hope for emigrating citizens from every country in Europe as they try to secure visas for passage by ship – any ship – out of Europe and away from the Nazis. For Americans with valid passports, life is more secure. The U.S. government has commandeered the S. S. Manhattan to transport stranded Americans in Lisbon back to New York. For these people, the biggest challenge is to pass the time till the ship sails, and many of them do it in extravagant fashion. A few, however, including characters here, have more difficulty leaving Europe, physically and emotionally, than one might expect. As one character notes, in retrospect, “Now it seems churlish to speak of our plight, which was nothing compared with that of real refugees – the Europeans, the Jews, the European Jews. Yet at the time, we were too worried about what we were losing to care about those who were losing more.” Author David Leavitt, in describing life in Lisbon in these crucial weeks before war engulfs all of Europe, examines four characters – three of them Americans awaiting the S. S. Manhattan – as they reveal their attitudes toward Europe, toward the United States, and ultimately toward each other.

Lisbon, 1940, provides a temporary safe haven and hope for emigrating citizens from every country in Europe as they try to secure visas for passage by ship – any ship – out of Europe and away from the Nazis. For Americans with valid passports, life is more secure. The U.S. government has commandeered the S. S. Manhattan to transport stranded Americans in Lisbon back to New York. For these people, the biggest challenge is to pass the time till the ship sails, and many of them do it in extravagant fashion. A few, however, including characters here, have more difficulty leaving Europe, physically and emotionally, than one might expect. As one character notes, in retrospect, “Now it seems churlish to speak of our plight, which was nothing compared with that of real refugees – the Europeans, the Jews, the European Jews. Yet at the time, we were too worried about what we were losing to care about those who were losing more.” Author David Leavitt, in describing life in Lisbon in these crucial weeks before war engulfs all of Europe, examines four characters – three of them Americans awaiting the S. S. Manhattan – as they reveal their attitudes toward Europe, toward the United States, and ultimately toward each other.

By using Lisbon primarily as an incidental setting for the characters’ lives, and not as the main focus of the novel, Leavitt provides an unusual vantage point from which to approach the horrors of the war and its psychological effects on those trying to escape it. Two couples, Pete and Julia Winters, and Edward and Iris Freleng, meet for the first time at the Café Suica, when (in a symbolic moment) Edward Freleng inadvertently crushes Pete’s eyeglasses as they fall to the pavement. The couples, both in their early forties, become friendly, though superficially they have little in common. Pete, from Indianapolis, has been working most of his life as a car salesman, while his Jewish wife Julia, from New York, has dreamed all her life of having an apartment in Paris, a goal which the two have recently achieved.

Edward and his British wife Iris come from more privileged backgrounds, with Edward admitting that he has “never had a job in [his] life.” He and Iris have lived in dozens of hotels and resorts all over Europe and write mystery novels for fun under the name of Xavier Legrand.

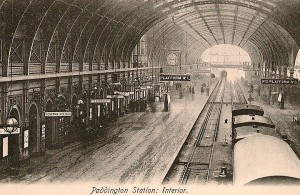

The differences between the couples are further emphasized through their different addresses in Lisbon. While Pete and Julia are lucky to have found a hotel room at all, at the Francfort Hotel near the Café Suica, Edward and Iris are staying at the similarly named Hotel Francfort, a different, more elegant hotel near the Santa Justa Elevator, which allows people on the street to travel from ground level to the much higher levels of the hillside without the effort of climbing on foot, the Elevator also symbolizing the differences between the two couples themselves.

The two couples have far more in common in their secret lives than they do in the superficial lives which initially bring them together. Before fifteen pages have elapsed, Edward is flirting with Pete, and Pete is not discouraging him. The women, too, have secrets which are revealed in the course o f the novel, and as the time for the departure of the Manhattan gets closer, their behavior becomes more and more frantic, with Julia insisting that she cannot possibly return to New York, and Iris manipulating Pete and Edward in order to maintain her own sanity and her own sense of power. The women and men go in different directions for much of the novel, enjoying many hours of independence from each other, with their activities often fueled, in the case of Pete and Edward, by absinthe, “the green fairy.” Julia continues to play games of solitaire throughout the novel, Iris continues to play power games, and the tensions within all the relationships get closer to the breaking point.

f the novel, and as the time for the departure of the Manhattan gets closer, their behavior becomes more and more frantic, with Julia insisting that she cannot possibly return to New York, and Iris manipulating Pete and Edward in order to maintain her own sanity and her own sense of power. The women and men go in different directions for much of the novel, enjoying many hours of independence from each other, with their activities often fueled, in the case of Pete and Edward, by absinthe, “the green fairy.” Julia continues to play games of solitaire throughout the novel, Iris continues to play power games, and the tensions within all the relationships get closer to the breaking point.

While the characters are developing, the author also includes a few of their observations of life around them, adding to the picture of life in Lisbon during the emergency. Refugees sleep on the beach and in chairs in hotels, if they are lucky. A shortage of food supplies in Lisbon and throughout Europe brings volunteer church groups from the US to try to help. For wealthy refugees, obtaining a car and a driver’s license has become almost impossible, a “hardship” for them in their boredom as they await their ship, and one Jewish couple whom Pete and Julia know has been unable to get a visa to the United States, Argentina, Brazil, Mexico, or Cuba, though they might get one from Cambodia, “for a price.” Particularly poignant is Pete’s witnessing of the beating of two eight-year-old children, each one wearing only one shoe, by the police of Antonio de Oliveira Salazar’s regime. Salazar has proclaimed that everyone in Lisbon must wear shoes because he believes that this shoe policy will “bring the country up to snuff for Lisbon’s Exposition [of 1940]” which he hopes will rival the 1939 World’s Fair in New York. The boys’ poor family can afford only one pair of shoes for two children.

Intriguing in its focus, the novel maintains its pace and keeps the reader entertained and interested throughout, despite the fact that the characters are not as fully developed as one might wish for. The insights into their characters are based primarily on their superficial, outward behavior and upon secrets from the past which are sometimes withheld until the conclusion, preventing the reader from fully understanding the characters and their motivations as the novel unfolds. None of the characters can be considered “heroes” by any standards, nor are they in any way admirable. Obvious symbols abound – from the title and the Elevator to Julia’s constant playing of solitaire, the depiction of the Winters’s apartment in Vogue magazine, and the meeting between Pete and Edward at the crumbling Castelo de Sao Jorge, with its ubiquitous peacocks. The conclusion, a tour de force, with its commentary on the writing process itself, will intrigue (and perhaps amuse) lovers of literary fiction. All in all, Leavitt creates an unusual treatment of a tension-filled time and place with characters whom he manipulates effectively to illustrate his themes. Ultimately, “there are occasions when none of the choices are good. You simply have to calculate which is the least bad.”

Photos, in order: The author’s photo is from http://www.nndb.com/

The Santa Justa Elevator, by Luca Galuzzi, may be found on http://en.wikipedia.org

Absinthe, “the green fairy,” is depicted here: http://www.alandia.de/

The photo of Antonio de Oliveira Salazar, leader of Portugal, is from http://en.wikipedia.org

The peacock from the medieval Castelo de Sao Jorge in Lisbon is shown on http://www.thenyloncarryall.com, part of an article by Katy Scrogin.

The medieval Castelo de Sao Jorge, which was crumbling in 1940, when the novel takes place, has been restored in recent years. http://en.wikipedia.org/

ARC: Bloomsbury

The Halloweens of my childhood were times in which our imaginations ran riot with mysterious haunted houses, the terrifying old “witches” who inhabited them, and the ghosts and other presences who kept them company. The scariest film I’d ever seen was “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow,” with its Headless Horseman, nothing like the films of today. Memories of old stories like these come roaring back to life with this Dickensian melodrama, set outside of Norfolk, England, in 1867. Eliza Caine, who has suffered a series of personal disasters which have left her an orphan, has made a sudden decision to leave the family “home” in London, in which she has spent her life, to accept the position of governess for a family she does not know in a city she has never seen. She is anxious for change, however. Just one week past, her father had ignored her pleas that he remain at home to nurse his cold and had, instead, attended a reading by Charles Dickens on a miserable, rainy night. He succumbed to fever shortly afterward. Almost immediately after her father’s death, Eliza is informed that the family home is not, in fact, owned by the family, and that she will have to vacate the house. Seeing an advertisement in the newspaper for a governess, signed by “H. Bennet,” she has chosen to leave her current teaching job at a girls’ school and move elsewhere.

The Halloweens of my childhood were times in which our imaginations ran riot with mysterious haunted houses, the terrifying old “witches” who inhabited them, and the ghosts and other presences who kept them company. The scariest film I’d ever seen was “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow,” with its Headless Horseman, nothing like the films of today. Memories of old stories like these come roaring back to life with this Dickensian melodrama, set outside of Norfolk, England, in 1867. Eliza Caine, who has suffered a series of personal disasters which have left her an orphan, has made a sudden decision to leave the family “home” in London, in which she has spent her life, to accept the position of governess for a family she does not know in a city she has never seen. She is anxious for change, however. Just one week past, her father had ignored her pleas that he remain at home to nurse his cold and had, instead, attended a reading by Charles Dickens on a miserable, rainy night. He succumbed to fever shortly afterward. Almost immediately after her father’s death, Eliza is informed that the family home is not, in fact, owned by the family, and that she will have to vacate the house. Seeing an advertisement in the newspaper for a governess, signed by “H. Bennet,” she has chosen to leave her current teaching job at a girls’ school and move elsewhere.

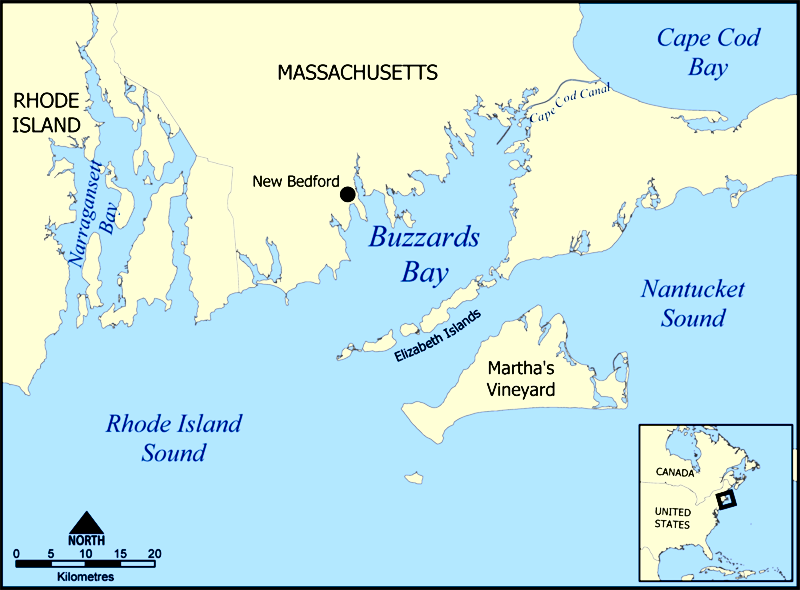

In this magnificent novel of family relationships, which is also a love story and a story of betrayal on several levels, author Jhumpa Lahiri introduces four generations of one family whose history begins in their home in Tollygunge, outside of Calcutta, and then moves off in many different directions. Traveling back and forth in time, with points of view shifting among several different but interrelated characters, the novel creates an impressionistic picture of events which begin in 1967 with a political uprising, the family effects of which continue into the present. Two brothers, only fifteen months apart in age, become linchpins of the novel. Subhash, the older, more cautious brother, is far more apt to watch any action, even as a child, than his brother Udayan, the more adventuresome brother, who is always participating in the action and testing limits. As they grow up, the brothers remain close, even as they move in different directions for college, with Subhash studying chemical engineering at one college, while Udayan studies physics at another.

In this magnificent novel of family relationships, which is also a love story and a story of betrayal on several levels, author Jhumpa Lahiri introduces four generations of one family whose history begins in their home in Tollygunge, outside of Calcutta, and then moves off in many different directions. Traveling back and forth in time, with points of view shifting among several different but interrelated characters, the novel creates an impressionistic picture of events which begin in 1967 with a political uprising, the family effects of which continue into the present. Two brothers, only fifteen months apart in age, become linchpins of the novel. Subhash, the older, more cautious brother, is far more apt to watch any action, even as a child, than his brother Udayan, the more adventuresome brother, who is always participating in the action and testing limits. As they grow up, the brothers remain close, even as they move in different directions for college, with Subhash studying chemical engineering at one college, while Udayan studies physics at another.

This dramatic quotation instantly establishes the intensity of this new novel from Sweden by Anna Jansson, candidate for the Glass Key Award for Best Scandinavian Novel in 2012 for its story involving a pandemic of bird flu on an island off the Swedish coast. A new name to American readers, Anna Jansson has had a dual career as both a nurse and a writer, and has already sold over two million copies of her Nordic crime novels throughout ten countries in Europe. This novel, the first in the Maria Wern series to be translated into English, is also the inaugural hard-copy novel by her publisher, Stockholm Text, which for the past two years has published only e-books, releasing seventeen of them in that short time and dramatically increasing the name recognition of Anna Jansson and the publisher’s other Nordic crime authors. Now available to an English-speaking audience, Strange Bird will undoubtedly captivate new readers, sweeping them up with the provocative opening chapters, as the action begins on Gotland, a sparsely inhabited island in the Baltic, sixty miles off the coast of Sweden. Unlike most noir novels, this novel involves characters one comes to appreciate for their simple honesty and the genuine feelings they convey for each other.

This dramatic quotation instantly establishes the intensity of this new novel from Sweden by Anna Jansson, candidate for the Glass Key Award for Best Scandinavian Novel in 2012 for its story involving a pandemic of bird flu on an island off the Swedish coast. A new name to American readers, Anna Jansson has had a dual career as both a nurse and a writer, and has already sold over two million copies of her Nordic crime novels throughout ten countries in Europe. This novel, the first in the Maria Wern series to be translated into English, is also the inaugural hard-copy novel by her publisher, Stockholm Text, which for the past two years has published only e-books, releasing seventeen of them in that short time and dramatically increasing the name recognition of Anna Jansson and the publisher’s other Nordic crime authors. Now available to an English-speaking audience, Strange Bird will undoubtedly captivate new readers, sweeping them up with the provocative opening chapters, as the action begins on Gotland, a sparsely inhabited island in the Baltic, sixty miles off the coast of Sweden. Unlike most noir novels, this novel involves characters one comes to appreciate for their simple honesty and the genuine feelings they convey for each other.

Though he has been lauded by Roberto Bolano and many other Latin American authors and critics, Guatemalan author Rodrigo Rey Rosa, has been a well-kept secret to most English-speaking readers. Of his almost two dozen works published to acclaim in Latin America, only four have been published in English, and three of those are translations into English by famed American expatriate author Paul Bowles, who was Rey Rosa’s literary mentor. Living in Morocco while he translated several of Paul Bowles’s novels into Spanish, Rey Rosa came to know the country well, finding life on the African shore of the Mediterranean markedly different from that of the European shore represented by France and Spain, both of which had claimed Morocco as a protectorate until after the mid-1950s. Rey Rosa’s most recent novel to be translated (by Jeffrey Gray), The African Shore, sweeps the reader into a world in which Europeans still see some aspects of their cultures in Morocco in the late 1990s – the varied cultures contributing to a Moroccan society that is often magical, elusive, and mysterious, but which is also filled with ominous hints about a future which may change dramatically as the country continues in its own direction and establishes its own identity under its own leaders.

Though he has been lauded by Roberto Bolano and many other Latin American authors and critics, Guatemalan author Rodrigo Rey Rosa, has been a well-kept secret to most English-speaking readers. Of his almost two dozen works published to acclaim in Latin America, only four have been published in English, and three of those are translations into English by famed American expatriate author Paul Bowles, who was Rey Rosa’s literary mentor. Living in Morocco while he translated several of Paul Bowles’s novels into Spanish, Rey Rosa came to know the country well, finding life on the African shore of the Mediterranean markedly different from that of the European shore represented by France and Spain, both of which had claimed Morocco as a protectorate until after the mid-1950s. Rey Rosa’s most recent novel to be translated (by Jeffrey Gray), The African Shore, sweeps the reader into a world in which Europeans still see some aspects of their cultures in Morocco in the late 1990s – the varied cultures contributing to a Moroccan society that is often magical, elusive, and mysterious, but which is also filled with ominous hints about a future which may change dramatically as the country continues in its own direction and establishes its own identity under its own leaders.