“Solomon Time plays by nobody’s rule, yet it loosely dictates that something may happen a little late or perhaps a little early or days late or even days early; it may have happened already or it may never happen at all. Schedules and timetables become irrelevancies, arrangements, meetings, deadlines inconsequential.”

Wi ll Randall, though a high school French teacher for ten years, is really just a kid–thirty-two years old, to be sure, but still young in his attitudes, in his responses to people, and in his views of what life, and his own life, in particular, are all about. Unsophisticated and incurious, he has seemingly let life happen to him, sometimes complaining about his job and the usual teacher/student/ administration problems, but never taking action to change his life. Or not, at least, until his friend Charles suggests that he give up his job and go to the Solomon Islands.

ll Randall, though a high school French teacher for ten years, is really just a kid–thirty-two years old, to be sure, but still young in his attitudes, in his responses to people, and in his views of what life, and his own life, in particular, are all about. Unsophisticated and incurious, he has seemingly let life happen to him, sometimes complaining about his job and the usual teacher/student/ administration problems, but never taking action to change his life. Or not, at least, until his friend Charles suggests that he give up his job and go to the Solomon Islands.

Charles is an executor of the will of a recently deceased Englishman known as the Commander, a man who established a small cocoa and coconut plantation in the Solomon Islands after World War II, lived there for thirty years, and then returned to England to retire. Always concerned for the people who had worked the plantation and those he had come to know in the village, he had, for the rest of his life, remembered their birthdays, sent Christmas cards, and kept in touch with the village, located on one of the remote Solomon Islands. The Commander has recently died, and in his will, he has left money for the benefit of the islanders, hoping that someone will go there to develop a reliable industry that will provide the villagers with income they can use for community improvements. His friend Charles thinks Will Randall will be a good candidate to go there. Almost by accident, and under the influence of cocktail party libations, Randall finds himself agreeing to go, once again, not having made a decision so much as just going with the flow.

Living in the remote community of Munda on New Georgia Island without the “necessities of life,” provides Randall with an opportunity to experience a delayed coming of age, a process he documents in this good-humored tale, filled with delightful characters and observations about life in a community in which there is little change. Ingenuous and unambitious, he quickly leaves behind his preconceived notions of what he should be doing with his life, and falls into the lullaby rhythms of life in the tropics, where “It was quite acceptable,” he discovered, “to do nothing but simply enjoy the natural beauty of the world about [him] and the genuine, nonjudgmental friendship of the sweet-tempered villagers.” His primary worry, upon first being ensconced in his small cottage, is whether one of the island’s six varieties of rats will fall on his head while he is sleeping.

He soon becomes part of the life there, conveying something of the spirit of the island in this mellow, often wry, account of his search for a way to help the village. He eventually decides they should all raise chickens, not only as a way to provide income but also as a way to expand their limited diet. Describing village philosophy and mores from the cannibalism which existed until the early 20th century to the devout Christianity and twice-a-day services which are held there now, Randall also fills his account with stories about the villagers themselves, educates the reader in the structure of pidgin (in which much of dialogue is related), briefs the reader on the World War II history of the nearby island of Guadalcanal, retells the story of JFK and PT-109, which went down in the Solomon Islands, and describes his own personal disasters, mocking himself at one point, as he finds himself swimming through shark-filled waters to an uninhabited island after falling overboard while his motorized canoe continues on its way.

Told with easy-going hu mor, this is light, entertaining reading-Randall is far more interested in telling a story than in contemplating his inner growth or making weighty observations about what he has learned. He pokes fun at himself and at the one or two “villains” he encounters as he sets up the chicken-business, and since life is pretty much the same on a daily basis, he concentrates on expanding specific, amusing episodes from his stay, rather than developing any deep or universally meaningful conclusions about them. His decision to return to England, in fact, comes suddenly, with no fanfare and even less explanation. He merely says, “More than once during my stay in the Solomons I had almost felt that we were [one big, happy family], but there was now a part of me that wanted to see other family and friends, and also wanted to find out how I would now react to the place from whence I had come.” Only fifty-four words later, he is on the jetty telling the leader of the village that he is going home, offering no further reflections on his life there or clues about what he has learned and why he has chosen this particular time to leave.

mor, this is light, entertaining reading-Randall is far more interested in telling a story than in contemplating his inner growth or making weighty observations about what he has learned. He pokes fun at himself and at the one or two “villains” he encounters as he sets up the chicken-business, and since life is pretty much the same on a daily basis, he concentrates on expanding specific, amusing episodes from his stay, rather than developing any deep or universally meaningful conclusions about them. His decision to return to England, in fact, comes suddenly, with no fanfare and even less explanation. He merely says, “More than once during my stay in the Solomons I had almost felt that we were [one big, happy family], but there was now a part of me that wanted to see other family and friends, and also wanted to find out how I would now react to the place from whence I had come.” Only fifty-four words later, he is on the jetty telling the leader of the village that he is going home, offering no further reflections on his life there or clues about what he has learned and why he has chosen this particular time to leave.

Randall is so descriptive in his writing style, and concentrates so much on trying to be entertaining, that he sometimes mixes metaphors and similes into a colorful but almost incomprehensible jumble. At one point, he describes Honiara, the capital, as “the unsightly boil in the navel of the otherwise dazzling [islands],” an image that is difficult to imagine, especially since, in the next sentence, he comments that “this is little more than a minor blemish.” In the same sentence, he remarks that Honiara is “reminiscent of the cardboard set of a low-budget spaghetti Western,” and that it is “slouching like a hungover vagrant against the foothills of Tandachehe Ridge.” Still, despite such confusions in imagery, he succeeds in writing an enjoyable, often amusing story, which will keep readers of all ages entertained. In going to his remote tropical island, Randall has fulfilled every person’s secret dream.

Notes: The author’s photo appears on http://www.ukbotswanasociety.org

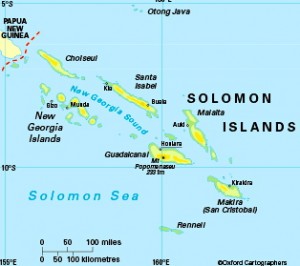

The map is from http://www.thecommonwealth.org

On the far left you will see New Georgia Islands, to the immediate northeast you will see Munda.

The Solomon Islands beach photo appears on http://www.theodora.com