“I was looking into writing a secret history of the Indonesian Islands in the Southeast, everything from Bali eastward. To me those islands were like a lost world where everything remained true and authentic, away from the gaze of foreigners–a kind of invisible world, almost…We needed a history of our country written by an Indonesian, something that explored nonstandard sources that Westerners could not easily reach.”

Aware that nearly all the history books about Indonesia begin with the discovery of the sea routes from Europe to Asia, thereby reflecting a western slant, a young teaching assistant in Jakarta in 1964 reflects the growing desire among Indonesians for a history of “their own.” Indonesia had been a Dutch colony for three and a half centuries, and had been occupied by the Japanese for much of World War II. Though long-time leader Dewi Sukarno declared the country’s independence–and became President–after the defeat of the Japanese, the Dutch remained a dominating presence in the country’s economy, to their own benefit far more than the Indonesians’. By 1964, when this novel opens, resentment against westerners is peaking. The Dutch are being arrested without warning and forcibly “repatriated,” the Chinese and Russians are exerting significant influence, Communism has become so popular that the president and the army fear a coup, and violence has become a way of life. “The police can kill anyone nowadays,” a teacher remarks, “and we just say, ‘Hey, there’s a dead body,’ without really knowing, or caring, who it was.”

that nearly all the history books about Indonesia begin with the discovery of the sea routes from Europe to Asia, thereby reflecting a western slant, a young teaching assistant in Jakarta in 1964 reflects the growing desire among Indonesians for a history of “their own.” Indonesia had been a Dutch colony for three and a half centuries, and had been occupied by the Japanese for much of World War II. Though long-time leader Dewi Sukarno declared the country’s independence–and became President–after the defeat of the Japanese, the Dutch remained a dominating presence in the country’s economy, to their own benefit far more than the Indonesians’. By 1964, when this novel opens, resentment against westerners is peaking. The Dutch are being arrested without warning and forcibly “repatriated,” the Chinese and Russians are exerting significant influence, Communism has become so popular that the president and the army fear a coup, and violence has become a way of life. “The police can kill anyone nowadays,” a teacher remarks, “and we just say, ‘Hey, there’s a dead body,’ without really knowing, or caring, who it was.”

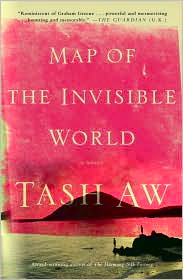

Malaysian author Tash Aw, in his second novel, recreates this turbulent period, and he does so on several levels at once. In a non-linear narrative which switches back and forth in time and among several main characters and plot lines, the author emphasizes the displacement and loss felt by people of all backgrounds within the country. Many Dutch have become permanent residents of Indonesia and though they consider it their home, they are being expelled. The country’s many poor and hungry feel ignored by their government, and rebellious students feel powerless to effect change.

All the main characters are to some extent lost or displaced. Adam, a teenage orphan who has lost his mother, his brother, and eventually his adoptive father, is particularly alienated, not sure who he really is and desperate to find out. His adoptive father Karl, a Dutch artist who has worked for many years in Perdo, a remote island, has just been arrested and taken away by military police, ostensibly to be repatriated to Holland, and Adam cannot find him. Margaret Bates, a middle-aged American expatriate doing research on non-verbal communication (an “invisible world” of its own) lives in Old Jakarta and considers herself Indonesian, but she has no close family ties and no lover. Her teaching assistant Din, a communist, is committed to helping the poor, but he is frustrated at the inaction of the Indonesian government. The secret lives, invisible lives, of all these characters are revealed as part of the novel’s mosaic-like structure.

All the main characters are to some extent lost or displaced. Adam, a teenage orphan who has lost his mother, his brother, and eventually his adoptive father, is particularly alienated, not sure who he really is and desperate to find out. His adoptive father Karl, a Dutch artist who has worked for many years in Perdo, a remote island, has just been arrested and taken away by military police, ostensibly to be repatriated to Holland, and Adam cannot find him. Margaret Bates, a middle-aged American expatriate doing research on non-verbal communication (an “invisible world” of its own) lives in Old Jakarta and considers herself Indonesian, but she has no close family ties and no lover. Her teaching assistant Din, a communist, is committed to helping the poor, but he is frustrated at the inaction of the Indonesian government. The secret lives, invisible lives, of all these characters are revealed as part of the novel’s mosaic-like structure.

Composed with great attention to detail, the novel suggests, rather then tells about, what is going on in the “invisible worlds” of these characters. The story is cumulative, consisting of dramatic, usually short, scenes which require the reader to draw conclusions from the accretion of details about the characters, their lives, and their relationships. At one point, for example, the typeface changes and becomes the story of Johan, whom we know to be Adam’s “lost” brother, but for most of the book we don’t know much about him, where he lives, how he was separated from his brother, or what the time frames of his various commentaries are. All we know is that he believe s “There’s nowhere for [him] to go.” Somehow Adam finds Margaret, but we don’t know, at first, how or why, or what connection they may have. And we don’t know much about Karl and his life till near the end. The plot develops on several planes at once, constantly creating suspense and constantly providing the reader with surprises, as each new piece of the puzzle falls into place–but then creates new complications to be resolved.

s “There’s nowhere for [him] to go.” Somehow Adam finds Margaret, but we don’t know, at first, how or why, or what connection they may have. And we don’t know much about Karl and his life till near the end. The plot develops on several planes at once, constantly creating suspense and constantly providing the reader with surprises, as each new piece of the puzzle falls into place–but then creates new complications to be resolved.

Very dramatic and often very exciting scenes from past and present occur in rapid succession, keeping the reader’s interest high, as we wonder whether Adam will find his brother and/or his adoptive father, whether Karl is still alive, whether Margaret will resolve her old feelings for a past lover, and whether revolution and bloodshed will sweep through Jakarta and catch up all the characters we have come to know. In some sense, however, the novel has almost an embarrassment of riches. The novel is explosive, like Indonesia itself, with a surfeit of characters acting and interacting in seemingly random fashion until coincidence brings them together in shocking new ways. The reader may actually become a bit weary from the bombardment of surprises unfolding in the lives of the many characters.

The ending feels a bit rushed, as if the author were not sure how to present a grand finale after having had so much drama up to that endpoint, and a few scenes feel gratuitous, and even manipulative of the reader, not adding to the story significantly. Over all, however, Tash Aw has created an absorbing and unusual novel about a time in which the future of Indonesia hangs in the balance, connected to the lives of the characters in invisible ways and presaging a history which no westerner wants to see.

Notes: The author’s photo appears on http://i.dailymail.co.uk

The Ravana mask from Indonesia appears on http://www.columbia.edu