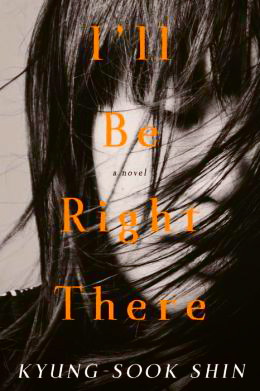

Note: Author Kyung-sook Shin is the first female WINNER of the Man Asian Literary Prize (2012). She is also WINNER of the French Prix de l’Inapercu and ten major awards in Korea.

“Looking back on your twenties, what would you most want to say to those of us who are going through our twenties now,” a student asks the professor.

“I hope you all have someone who always makes you want to say, Let’s remember this day forever…[and] I hope you will never hesitate to say, I’ll be right there,” the professor responds.

Although lovers of international fiction can find a number of novels in translation from Japan, China, and other Asian countries available in English, the number of novels from Korea is comparatively small. Though I actively look for novels from as many countries as possible, I have, in fact, reviewed only one other Korean novel on this website to date – Three Generations, by Yom Sang-Soep, a classic written in 1931. Kyung-sook Shin’s new novel, I’ll Be Right There, translated by Sora Kim-Russell, has therefore introduced me to a new, contemporary literary world, and I hope that other readers interested in unusual and rewarding fiction from an author who is almost unknown in the US will feel as enriched by her work as I do. I’ll Be Right There takes place during the turbulent 1980s, a time in which Korean students demonstrated against the military dictatorship which had seized their country in a coup in 1979. It was partly because of these demonstrations, leading to the well-publicized torture death of a student, that the country’s leadership finally announced in 1987 that the direct election of a President would finally take place.

Although lovers of international fiction can find a number of novels in translation from Japan, China, and other Asian countries available in English, the number of novels from Korea is comparatively small. Though I actively look for novels from as many countries as possible, I have, in fact, reviewed only one other Korean novel on this website to date – Three Generations, by Yom Sang-Soep, a classic written in 1931. Kyung-sook Shin’s new novel, I’ll Be Right There, translated by Sora Kim-Russell, has therefore introduced me to a new, contemporary literary world, and I hope that other readers interested in unusual and rewarding fiction from an author who is almost unknown in the US will feel as enriched by her work as I do. I’ll Be Right There takes place during the turbulent 1980s, a time in which Korean students demonstrated against the military dictatorship which had seized their country in a coup in 1979. It was partly because of these demonstrations, leading to the well-publicized torture death of a student, that the country’s leadership finally announced in 1987 that the direct election of a President would finally take place.

The novel’s Prologue opens in the present with main character Jung Yoon receiving a phone call from someone to whom she had obviously once been close, but with whom she has had no contact at all for eight years. Her caller reveals that Prof. Yoon (no relation to Jung Yoon), the literature professor whom she and her friends had all revered, lies dying in the hospital. Quickly involving the reader, who wants to know more about Jung Yoon and her life, the author provides details about the professor’s influence on Jung Yoon and hints at the mysterious relationship Jung Yoon has had with Myungsuh Yi, the man who has phoned her. When Miyungsuh asks if he can come over to her place, however, Yoon cruelly rebuffs him. “It seems that whether we are aware of it or not, memory carries a dagger in its breast,” she remarks to the reader, as she realizes that she has just used the same words to rebuff him that he once used with her.

The college students frequently meet at the bench beneath the Zelkova tree. It is this tree type which is so frequently used for bonsai plants. Photo by Bonsai Anna

As Jung Yoon’s life in the 1980s unfolds, many American readers will be startled by the cultural differences – and similarities – between her life and theirs. When Yoon’s mother becomes terminally, ill, for example, she sends Yoon away to live with a female cousin for the entire four years she is in high school: “Everybody has to say goodbye eventually, [my mother] told me, so you may as well start practicing.” Jung Yoon never says that her mother was wrong, just that “we saw things differently.” It is not until her mother’s death that she takes a leave of absence from college and finally returns home to the countryside to reconnect with her father and her childhood friend Dahn. Dahn’s eventual decision to drop out of college to join the army introduces an ominous new element which echoes throughout the plot of the novel when he is assigned, ironically, to riot duty at the college.

From inside her apartment, Yoon looked out at the apartment buildings clustered at the base of Naksan Mountain

When she returns to college and Prof. Yoon’s class, Jung Yoon becomes friendly with two other students there, Myungsuh Yi, a male student, and his female friend Miru. The professor, fond of speaking in aphorisms, also recites poems from western authors and tells stories with moral lessons. A repeating story, which becomes symbolic, is that of Saint Christopher who was a “boatman with no boat,” who used his body to carry people across the river. One night as he is carrying a child, the child becomes almost impossibly heavy, just as the river starts rising precipitously. When Christopher barely makes it to the other side, Jesus appears, telling him that “When you crossed that river, you were carrying the world on your shoulders.” The professor notes for the students that “Each of you is both Christopher and the child he carries on his back…Only the student who truly savors this paradox will make it safely across. Literature and art are not simply what will carry you; they are also what you must lay down your life for.” Among the many authors whose writings are quoted here are Romain Rolland, Emily Dickinson, Roland Barthes, and Rainer Maria Rilke. The sad story of Kitty Genovese in New York is also recalled here.

Namsan Tower, with all its colors, is visible from Yoon's apartment and from many other points menioned in the novel.

Italicized notes from the Brown Notebook kept by Myungsuh Yi expand the narrative and point of view as the story progresses, including the beginnings of a love story, as Jung Yoon, Myungsuh, Miru, and Miru’s sister Mirae become almost constant companions. The students continue to make (sometimes ponderous) observations about their lives. Miru remarks that “to hold someone’s hand, you must first know when to let go.” Myungsuh quotes the professor as saying that “everyone has his or her own means of defining value,” and Myungsuh himself wishes that “someone would promise me that nothing is meaningless. I wish there were promises worth believing in.” Some characters, anticipating that they could disappear at any moment, begin recording their thoughts; others fail to “become St. Christopher” and do not respond quickly enough to cries for help (as happened with Kitty Genovese in New York). Still others cannot see the urgency of others’ needs through the pressures of their own. The novel concludes in the present, more than twenty years later, and resolves all the story lines.

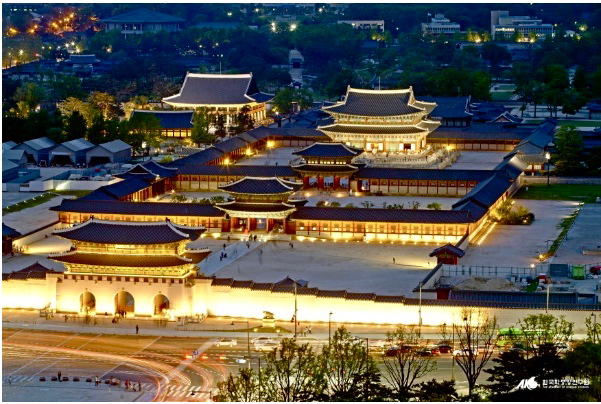

Yoon spent many afternoons visiting the Gyeongbokgun Palace museum. The famed Gwanghwamun Gate is in the lower left.

Though the novel is somewhat awkward at the beginning, with too many grand metaphysical statements, the complexities of the characters and their interactions soon take over, leading to a wonderfully rich and dramatic conclusion which explains some of the unusual decisions the characters make, especially regarding love. Ultimately, Jung Yoon herself “finally realized that I was not alone. Everything I saw and everything I felt belonged to [my departed friends], too…I was living their unfinished time with them,” an epiphany which gives some resolution to her own imperfect life.

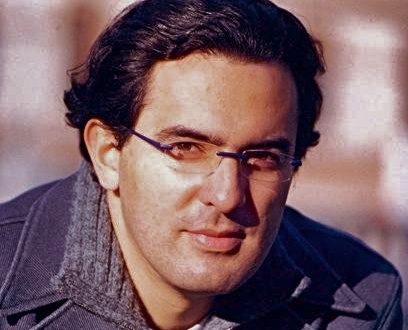

Photos, in order: The author’s photo is from http://www.deutschlandradiokultur.de

Yoon and her friends often gathered at the bench under the zelkova tree. This type of tree is one of the most popular trees for bonsai. Photo here by Bonsai Anna, taken, ironically in Visby, Gotland, Sweden.

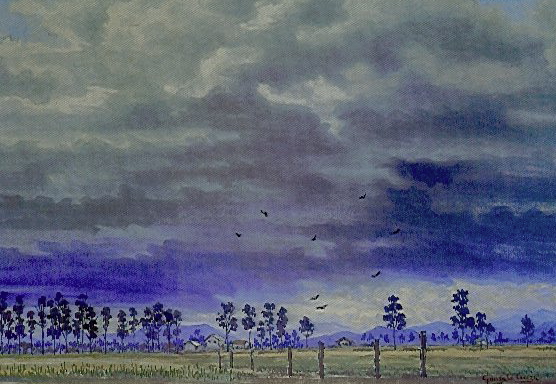

The "spider glyph," from the Nazca culture of Peru, 100 BC - 800 AD, was seen from the air by Yoon in her later years and inspired the epiphany of her life.

Naksan Mountain, which Yoon could see from her window, is found on http://seoulmateskorea.com/

The Namsan Tower, visible in the distance from Yoon’s apartment, and from several scenes in the novel, appears on http://namsan.wordpress.com

The Gyeongbokgun Palace museum, which Yoon often visited, is shown here, with the Gwanghwanmun entrance gate in the lower left: http://seoulmateskorea.com/

Seeing the “spider glyph” of the Nazca culture (100 B.C. to 800 A.D.) was a major moment for Yoon when she flew over this area in Peru many years after the time of the main action here. Those who read the book will understand this reference and the importance of the image. http://www.latinamericanstudies.org/

ARC: Other Press

A novel so rich it is difficult to describe in anything less than superlatives, Colombian author Juan Gabriel Vasquez’s The Sound of Things Falling mesmerizes with its ideas and captivating literary style, while also keeping a reader on the edge of the chair with its unusual plot, fully developed characters, dark themes, and repeating images. Set in Colombia, the novel opens in Bogota in 2009, with Antonio Yamarra, a law professor, reading a newspaper story about a male hippopotamus which had escaped from the untended zoo belonging to former drug lord Pablo Escobar, who was shot and killed in 1993. The hippo, one of several living free and breeding on the huge Escobar property in the sixteen years since Escobar’s death, had eventually wreaked havoc in the surrounding countryside until it was shot and killed by a marksman. The fate of the hippo’s mate and baby, which had escaped with him, were then unknown. The newspaper’s image of the slaughtered hippo brings back traumatic memories for Yamarra – real memories involving a former acquaintance, Ricardo Laverde, whom he had known for a few months in 1996, until Laverde’s death later that year, and more subtle images of a family destroyed and some possible connections to Colombia’s on-going war against drugs.

A novel so rich it is difficult to describe in anything less than superlatives, Colombian author Juan Gabriel Vasquez’s The Sound of Things Falling mesmerizes with its ideas and captivating literary style, while also keeping a reader on the edge of the chair with its unusual plot, fully developed characters, dark themes, and repeating images. Set in Colombia, the novel opens in Bogota in 2009, with Antonio Yamarra, a law professor, reading a newspaper story about a male hippopotamus which had escaped from the untended zoo belonging to former drug lord Pablo Escobar, who was shot and killed in 1993. The hippo, one of several living free and breeding on the huge Escobar property in the sixteen years since Escobar’s death, had eventually wreaked havoc in the surrounding countryside until it was shot and killed by a marksman. The fate of the hippo’s mate and baby, which had escaped with him, were then unknown. The newspaper’s image of the slaughtered hippo brings back traumatic memories for Yamarra – real memories involving a former acquaintance, Ricardo Laverde, whom he had known for a few months in 1996, until Laverde’s death later that year, and more subtle images of a family destroyed and some possible connections to Colombia’s on-going war against drugs.

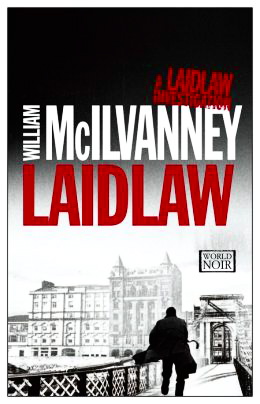

In this classic novel from 1977, Scottish author/poet William McIlvanney pulls out all the literary stops, creating a novel so filled with ideas, unique descriptions, and unusual characters that labeling it as one of the great crime novels does it a disservice. It is also a literary novel of stunning originality, so unusual for its time that it is now labeled as the first of the “Tartan noir” novels, with McIlvanney himself described as the “Scottish Camus.”* Two sequels –

In this classic novel from 1977, Scottish author/poet William McIlvanney pulls out all the literary stops, creating a novel so filled with ideas, unique descriptions, and unusual characters that labeling it as one of the great crime novels does it a disservice. It is also a literary novel of stunning originality, so unusual for its time that it is now labeled as the first of the “Tartan noir” novels, with McIlvanney himself described as the “Scottish Camus.”* Two sequels –

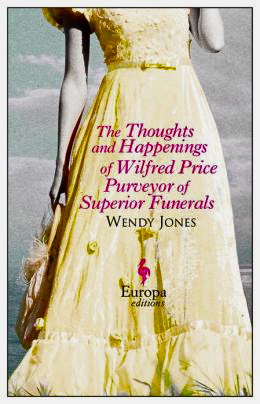

Already optioned for a miniseries by the producers of Downton Abbey, this novel has everything that will make this projected series a huge, popular success – a young, ingratiating main character who bumbles along as he tries to sort out his life; a woman to whom he becomes inadvertently engaged and who turns out to be a character worthy of great empathy; another woman who has still not recovered from her loss during World War I; and a Welsh setting in 1924 in Narberth, a small, rural town in Pembrokeshire in which everyone knows everyone else’s business. World War I is over, and the many young men from Narberth who were killed in the war have left behind broken hearts, ruined lives, and devastated families. Young men like Wilfred Price, who have not served in battle, have escaped many of the emotional horrors of the war, insulated from this reality because their professions have been considered essential to their communities.

Already optioned for a miniseries by the producers of Downton Abbey, this novel has everything that will make this projected series a huge, popular success – a young, ingratiating main character who bumbles along as he tries to sort out his life; a woman to whom he becomes inadvertently engaged and who turns out to be a character worthy of great empathy; another woman who has still not recovered from her loss during World War I; and a Welsh setting in 1924 in Narberth, a small, rural town in Pembrokeshire in which everyone knows everyone else’s business. World War I is over, and the many young men from Narberth who were killed in the war have left behind broken hearts, ruined lives, and devastated families. Young men like Wilfred Price, who have not served in battle, have escaped many of the emotional horrors of the war, insulated from this reality because their professions have been considered essential to their communities.

In this consummate homage to books, Guatemalan author Rodrigo Rey Rosa introduces the unnamed owner of a bookstore in Guatemala – a commercial rarity, he points out – before moving on to describe the bookseller’s life, the books he enjoys, his book-loving friends, and, ultimately the book thief who haunts his store and with whom he has fallen in love. Writing in clear language without fanciful flourishes, Rey Rosa tells a classic story of love and loss and life and death, and those looking for a simple love story with unusual characters in an exotic setting will be amply rewarded as they meet and follow Severina, the novel’s beautiful and unusual “heroine.”

In this consummate homage to books, Guatemalan author Rodrigo Rey Rosa introduces the unnamed owner of a bookstore in Guatemala – a commercial rarity, he points out – before moving on to describe the bookseller’s life, the books he enjoys, his book-loving friends, and, ultimately the book thief who haunts his store and with whom he has fallen in love. Writing in clear language without fanciful flourishes, Rey Rosa tells a classic story of love and loss and life and death, and those looking for a simple love story with unusual characters in an exotic setting will be amply rewarded as they meet and follow Severina, the novel’s beautiful and unusual “heroine.”