“The likeness of those who choose other patrons than Allah is as the likeness of the spider when she taketh unto herself a house, and lo! The frailest of all houses is the spider’s house, if they but knew.” –The Koran

Eerily prescient in its depiction of the desire of Islamic populations to establish sovereign Islamic governments and free themselves from tyranny in North Africa and the Middle East, this 1955 novel should have been a wake-up call to the western world half a century ago when it was written. Paul Bowles (1910 – 1999), an American expatriate author, musician, and screenwriter who lived in Morocco for over fifty years, was an eyewitness to the uprisings which occurred there in 1954 after the French deposed the much-loved Sultan Mohammed V. Morocco had been occupied jointly by the Spanish and French since 1912, when they divided the country into two spheres of influence and ruled as colonial powers, establishing their own more modern cities adjacent to those of the native population and imposing their own values and rules upon them.

in its depiction of the desire of Islamic populations to establish sovereign Islamic governments and free themselves from tyranny in North Africa and the Middle East, this 1955 novel should have been a wake-up call to the western world half a century ago when it was written. Paul Bowles (1910 – 1999), an American expatriate author, musician, and screenwriter who lived in Morocco for over fifty years, was an eyewitness to the uprisings which occurred there in 1954 after the French deposed the much-loved Sultan Mohammed V. Morocco had been occupied jointly by the Spanish and French since 1912, when they divided the country into two spheres of influence and ruled as colonial powers, establishing their own more modern cities adjacent to those of the native population and imposing their own values and rules upon them.

The tumult that developed in Fez in the wake of the Sultan’s removal, and the many factions that evolved within the local population in response to colonial high-handedness, will strike a familiar chord among contemporary readers who are now seeing exactly the same issues being addressed by residents of many other countries in the region, with the same kind of attendant violence provoking the same perplexity  among western powers. As one young Moslem* explains here, “If [we] cannot have freedom, at least [we] can have vengeance….Whatever you [infidels] make for us will be a spiderweb, an ankabutz, and may God, who forgives all, hear my words, because it’s the truth…”

among western powers. As one young Moslem* explains here, “If [we] cannot have freedom, at least [we] can have vengeance….Whatever you [infidels] make for us will be a spiderweb, an ankabutz, and may God, who forgives all, hear my words, because it’s the truth…”

The Prologue to this novel opens with John Stenham, an American author in his late thirties, an old hand in Morocco, leaving the home of a friend outside the walls of the “Old City” in Fez. His friend insists that he take a “protector” along with him that night as he travels back home to the Medina, a trip filled with tension, vibrantly described. No sooner does he arrive back at the hotel where he lives than he receives a phone call from Alain Moss, also living at the hotel, who must see him immediately. It is 1:20 a.m.

Bab Bou Jeloud, a gate to the Medina

The focus of the novel then shifts to that of Amar, a fourteen-year-old boy brought up in a poor, strictly traditional Moslem household. His brother Mustapha mocks and belittles him, and his father regularly beats him—so savagely, in recent days, that Amar has been bed-ridden for several days, unable even to eat. Though the family once lived comfortably, they have now lost all their property, and Amar, unable to pay the fees to attend school, is illiterate. As Amar, a naïf, moves around the city, unimpeded, talking to his boss, his family, and his young friends, the reader discovers through his eyes the many factions at work in this fraught time in Moroccan history.

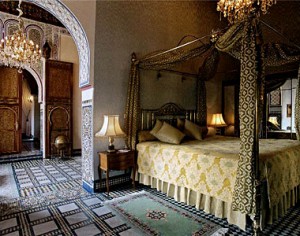

Bedroom in Palais Jamal, the model for the Merinides Hotel in the book

His father, like many others, wants the Sultan back on the throne and hints at promoting jihad against all unbelievers. The brother of a friend, recently arrested for bringing grenades into Fez from Spanish Morocco, is a member of Istiklal (meaning “Freedom”), a group of young men who intend to take matters into their own hands and oust the French and all other foreigners by violence. A group of young intellectuals has entered the country to promote Marxist/Leninist ideals, and the French themselves have enlisted the help of groups of Berbers to undermine the effects of the jihadists. The Mokhazni, a group of Arab locals, have been hired to work with the French, spy on their own people, and uphold French values. The Americans are not immune from the hatred: Because they have sold weapons to the French and because they have military bases to protect, they are almost as unpopular as the French with the populace. As the religious holiday of Eid approaches, Amar is convinced that something terrible is about to happen in Fez, but he also believes that “By inflicting punishment on unbelievers, the Moslems would merely be imposing divine justice.”

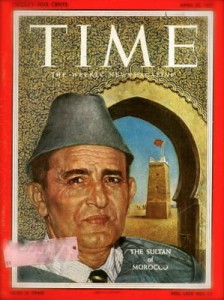

King Mohammed V of Morocco

In Part II, the author reintroduces Stenham and Moss, and also introduces Mme. Veyron, the former Polly Burroughs, an adventure-seeking American who has escaped her French husband to travel abroad. When she and Stenham connect, their “adventures” broaden the picture of what is happening in Fez and the immediate surroundings, though it is their inevitable connection with the more appealing character of Amar that gives the full picture. Despite his lack of education, Amar is far more intuitive about the nature of the Moroccan population than they have any hope of becoming. As Amar becomes more and more comfortable with the extreme views of the jihadists, the reader, too, becomes familiar with the dichotomy between the strict interpretations of Islam by some, and the desire of many Moslem residents to improve their lives on earth while also being observant Moslems.

Though the novel is sometimes “messy,” in its meandering plot and weak characterizations—Stenham and Polly Burroughs are flat characters and do not come alive the way Amar does, for example—the overall depiction of life in Morocco is compelling and dramatic. The atmosphere, almost palpable in its realism, is filled with scents, sounds, and vivid images.

The Medina in Fez

Many philosophical digressions serve to explain some of the mysteries of Islam for western readers. The de-emphasis on the individual, the belief that no matter what happens (for good or evil), it is Allah’s will and cannot be changed, and the emphasis on vengeance, are unusual concepts for westerners to deal with. And when Amar prays to Allah that Allah “might help [his people] discover new refinements in the matter of causing pain and despair, might show them the way to the imposing of hitherto undreamed of humiliation, degradation and agony,” the reader begins to understand what some of the current issues, there and in other parts of that area, involve. A novel to fascinate anyone who has any interest at all in the current issues rending North Africa and the Middle East, The Spider’s Web is an especially enlightening novel. How sad that it was written fifty-six years ago and published to a world that paid so little attention to the real, and ongoing, issues there.

ALSO by Paul Bowles: THE SHELTERING SKY

Bastila, a popular Moroccan specialty, which Stenham finds indigestible. See ingredients at the end of photo credits.

Note: *The author uses the spelling of “Moslem,” instead of “Muslim” throughout, and I have duplicated that spelling here.

Photos, in order: The author’s photo is from http://nopoboho.blogspot.com

The photo of Bab Bou Jeloud, a gate into the Medina, which features in the last part of the novel, is from: http://wn.com

According to the author, the Merinides Hotel, where Stenholm and Moss live, was modeled after the real Palais Jamai, here: http://www.concierge.com

The Time cover of Sultan Mohammed V is found here: http://radicalroyalist.blogspot.com (The Sultan was later restored to power and ruled Morocco from 1957 – 1961, after which he was succeeded by his son King Hassan II).

The Medina in Fez: http://www.panoramio.com

I was curious about the Moroccan specialty of bastila, which Stenham finds indigestible. It is easy to see why. It is pigeon pie, made with 1 ½ pounds of butter, a dozen eggs, almonds, cinnamon, onion, ginger, and allspice, with pastry covering all! Recipe by Clifford A Wright is here: http://www.cliffordawright.com