Note: This novel has been CHOSEN one of Modern Library’s 100 Best Novels.

“You know…the sky here is very strange. I often have the sensation when I look at it that it’s a solid thing up there, protecting us from what’s behind… I think we’re both afraid. And for the same reason. We’ve never managed, either one of us, to get all the way into life.” Port Moresby to his wife, Kit.

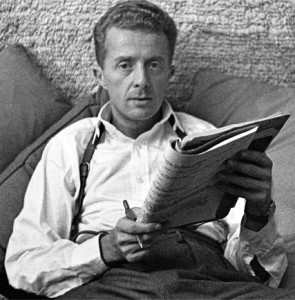

The Moresbys are about to get “all the way into life” in ways they have never expected. Having left the United States for an adventure in Morocco, main character Porter Moresby is careful to describe himself as a traveler, not a tourist. “The difference is partly one of time, he [explains]. Whereas the tourist generally hurries back home at the end of a few weeks or months, the traveler, belonging no more to one place than another, moves slowly, over periods of years, from one part of the earth to another.” This is the Moresbys’ first trip across the Atlantic since 1939, since all of Europe and much of Africa has been consumed for ten years with World War II and its aftereffects. In 1949, when they decide to do some traveling, North Africa is one of the few places to which they can obtain boat passage. Perhaps the unnamed Moroccan port where they arrive is Tangier, where author Paul Bowles took up residence in 1947 and where he lived as an expatriate for the remaining fifty-two years of his life, but the Moresbys do not specify which port, one port being pretty much the same as other ports, they seem to feel, as they immediately make plans to move into the interior of the country.

The Moresbys are about to get “all the way into life” in ways they have never expected. Having left the United States for an adventure in Morocco, main character Porter Moresby is careful to describe himself as a traveler, not a tourist. “The difference is partly one of time, he [explains]. Whereas the tourist generally hurries back home at the end of a few weeks or months, the traveler, belonging no more to one place than another, moves slowly, over periods of years, from one part of the earth to another.” This is the Moresbys’ first trip across the Atlantic since 1939, since all of Europe and much of Africa has been consumed for ten years with World War II and its aftereffects. In 1949, when they decide to do some traveling, North Africa is one of the few places to which they can obtain boat passage. Perhaps the unnamed Moroccan port where they arrive is Tangier, where author Paul Bowles took up residence in 1947 and where he lived as an expatriate for the remaining fifty-two years of his life, but the Moresbys do not specify which port, one port being pretty much the same as other ports, they seem to feel, as they immediately make plans to move into the interior of the country.

Married twelve years, but staying in separate bedrooms, the Moresbys are traveling with another American named Tunner, a single man enamored with their spontaneous style (and possibly with Kit). This threesome soon meets another couple – the Lyles, a mother and son from Australia – the mother being the singularly most obnoxious woman you will ever “meet.” All five participants in the journey are uniformly self-centered, superficial, spoiled, ignorant, and insensitive, and Bowles’s level of detail in showing the Lyles’ cringe-worthy lack of respect for the local culture through their insulting dialogue suggests that he has overheard dialogue like this more than once during his time in Tangier. The Moresbys, though less obvious in their blunders regarding the local population, are, nevertheless, setting themselves up for failure from the outset. When all five decide to travel to Boussif, the group splits up, Port Moresy traveling by car with the Lyles for five or six excruciating hours, and his wife Kit and Tunner taking the local train, a trip of ten to twelve hours made bearable only by their plentiful supply of champagne.

Married twelve years, but staying in separate bedrooms, the Moresbys are traveling with another American named Tunner, a single man enamored with their spontaneous style (and possibly with Kit). This threesome soon meets another couple – the Lyles, a mother and son from Australia – the mother being the singularly most obnoxious woman you will ever “meet.” All five participants in the journey are uniformly self-centered, superficial, spoiled, ignorant, and insensitive, and Bowles’s level of detail in showing the Lyles’ cringe-worthy lack of respect for the local culture through their insulting dialogue suggests that he has overheard dialogue like this more than once during his time in Tangier. The Moresbys, though less obvious in their blunders regarding the local population, are, nevertheless, setting themselves up for failure from the outset. When all five decide to travel to Boussif, the group splits up, Port Moresy traveling by car with the Lyles for five or six excruciating hours, and his wife Kit and Tunner taking the local train, a trip of ten to twelve hours made bearable only by their plentiful supply of champagne.

When he first arrives in Morocco, Port Moresby goes for a long walk through an old fort and into the hills.

Eventually, Port and Kit decide to travel together, hoping, belatedly, to revitalize their marriage. Both are so self-absorbed, however, that improvement seems unlikely, especially since Kit suffers from personal “terrors”, and Port, a nervous man to start with, begins to wake up from nightmares, sobbing in bed. In Ain Krorfa, as in the port where they first arrived, Port Moresby seeks a liaison with a local woman while his wife is sleeping. He also runs afoul of the commander of the military post of Bou Noura when he accuses a local corporal of having stolen his passport, only to have it found by Tunner.

The middle section of the book wanders a bit, lacking direction as much as the characters do, and focusing on Port and Kit’s personal problems, which are legion. When Port becomes ill with typhoid on his way to a town that has shut down because of a meningitis outbreak, they are forced to move on, eventually finding a primitive place to stay where Kit will be nursemaid to the seriously ill Port. “I’m very sick,” he confesses. “I don’t know whether I’ll come back.” Kit, however, gets tired of nursing and leaves him alone in the room, seriously ill, for hours when she “goes out,” justifying her behavior by noting that “He’s stopped being human…Illness reduces man to his basic state.” As his fever continues to rise, Port begins to panic, and he later begs Kit to stay beside him, because he is “so alone I can’t even remember the idea of not being alone. I can’t even think what it would be like for there to be someone else in the world.” He begs her to understand. As he fades in and out, Kit thinks, “He says it’s more than just being afraid. But it isn’t. He’s never lived for me. Never. Never,” a highly revealing thought, under the circumstances. Her later behavior is unconscionable. The final section continues Kit’s story as she tries to deal with new problems which threaten to overwhelm her.

Tunner and Kit Moresby go to Boussif by train. This is the 4th class car, where Kit gets trapped on a stop.

In this unusual and thoughtful debut novel, Bowles takes crass Americans out of their normal post-war environment, allowing the reader to see them in a more universal context. This is not a love story, by any means, despite Bernardo Bertolucci’s attempt to make it one in his 1990 film adaptation with Debra Winger and John Malkovich (see video trailer at end of review). Instead, the two main characters are so limited, both in their relationships with their peers and in relationships with the wider, outside world that neither is fully capable of feeling real emotion for anyone other than self. Life is reduced to its most basic essentials in the Sahara, and as they travel through it, ending finally in Sudan, they have opportunities to learn and grow but not the skills to do so. For Kit, who never really thinks, the last part of the journey is a horror, based largely on her own impulses and spontaneous actions. It is not possible to regard her behavior as decision-making, even very bad decision-making, since Kit has no long-term goals when she acts and no ability to foresee outcomes. She does not even elicit much sympathy because she is so manipulative.

The novel ultimately leads the reader into a good deal of introspection by raising the question of how much the characters fail because they are failures to begin with and how much they fail because they have never looked inside themselves or tested themselves in any serious way. One does not go on the ultimate test of strength and survival in the Sahara, as Port and Kit do, without any survival skills at all (and I am not talking about physical survival). Their casual “adventuring” in Morocco, while recently returned veterans at home are struggling with their memories of war and the aftereffects must have hit hard at the American readership when this novel was published. Bowles’s depiction of these thoughtless characters as Americans may go a long way toward explaining why he spent the last fifty-two years of his life living quietly and happily as an expatriate in Morocco.

ALSO by Paul Bowles: THE SPIDER’S HOUSE

NOTE: When this novel was published in 1949, it was first reviewed in the New York Times by Tennessee Williams. See http://www.nytimes.com/

Photos, in order: The author’s photo is from http://www.goodreads.com/

The Old Fort and Dades Gourges are part of a photo story by Emily Kiddy. The next photo of the windy road is also from her site, which I recommend heartily to all readers for the magnificent photos from all parts of Morocco: http://emilykiddy.blogspot.com/

The EngRail History site says that over a million passengers a year travel in the 4th class carriages through Morocco. http://www.engrailhistory.info/r052.html

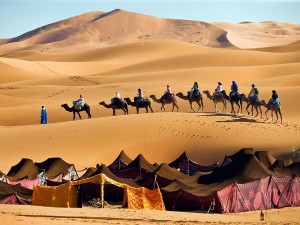

The camel caravan and tents appear on National Geographic:

http://travel.nationalgeographic.com/travel/countries/morocco

Bernardo Bertolucci’s film of THE SHELTERING SKY (1990) turns this novel into a love story, which it is not, but the photography is spectacular.