Note: This novel was WINNER of the 2014 IMPAC Dublin Award, WINNER of the Alfaguara Novel Prize in Spain, and WINNER of an English PEN Award.

“No one who lives long enough can be surprised to find their biography has been molded by distant events, by other people’s wills, with little or no participation from our own decisions. Those long processes that end up running into our life…tend to be hidden like subterranean currents, like tiny shifts of tectonic plates…and when the earthquake finally comes we invoke the words we’ve learned to calm ourselves, accident, fluke [or] fate.”

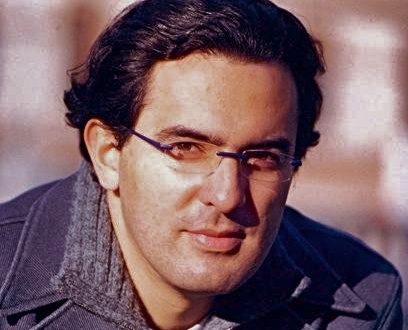

A novel so rich it is difficult to describe in anything less than superlatives, Colombian author Juan Gabriel Vasquez’s The Sound of Things Falling mesmerizes with its ideas and captivating literary style, while also keeping a reader on the edge of the chair with its unusual plot, fully developed characters, dark themes, and repeating images. Set in Colombia, the novel opens in Bogota in 2009, with Antonio Yamarra, a law professor, reading a newspaper story about a male hippopotamus which had escaped from the untended zoo belonging to former drug lord Pablo Escobar, who was shot and killed in 1993. The hippo, one of several living free and breeding on the huge Escobar property in the sixteen years since Escobar’s death, had eventually wreaked havoc in the surrounding countryside until it was shot and killed by a marksman. The fate of the hippo’s mate and baby, which had escaped with him, were then unknown. The newspaper’s image of the slaughtered hippo brings back traumatic memories for Yamarra – real memories involving a former acquaintance, Ricardo Laverde, whom he had known for a few months in 1996, until Laverde’s death later that year, and more subtle images of a family destroyed and some possible connections to Colombia’s on-going war against drugs.

A novel so rich it is difficult to describe in anything less than superlatives, Colombian author Juan Gabriel Vasquez’s The Sound of Things Falling mesmerizes with its ideas and captivating literary style, while also keeping a reader on the edge of the chair with its unusual plot, fully developed characters, dark themes, and repeating images. Set in Colombia, the novel opens in Bogota in 2009, with Antonio Yamarra, a law professor, reading a newspaper story about a male hippopotamus which had escaped from the untended zoo belonging to former drug lord Pablo Escobar, who was shot and killed in 1993. The hippo, one of several living free and breeding on the huge Escobar property in the sixteen years since Escobar’s death, had eventually wreaked havoc in the surrounding countryside until it was shot and killed by a marksman. The fate of the hippo’s mate and baby, which had escaped with him, were then unknown. The newspaper’s image of the slaughtered hippo brings back traumatic memories for Yamarra – real memories involving a former acquaintance, Ricardo Laverde, whom he had known for a few months in 1996, until Laverde’s death later that year, and more subtle images of a family destroyed and some possible connections to Colombia’s on-going war against drugs.

Flashing back to 1996, Yamarra shows the almost total control that the Escobar cartel had over many aspects of Colombian life for more than a dozen years from the early 1980s to early 1990s. “I’m not talking about the violence of cheap stabbing and stray bullets, the settling of accounts between low-grade dealers, but the kind that transcends the small resentments and small revenges of little people, the violence whose actors are collectives…the State, the Cartel, the Army, the Front.” On one day which Yamarra remembers from 1996, another shooting occurred, this time the death of the son of a former President, who was himself a candidate for President. At the time, Yamarra is playing billiards, where all the players, inured to such news bulletins on the TV, listen for a minute, then go back to their game, except for one person, Ricardo Laverde, a man in his forties, who remains riveted to the screen as the TV news switches to a new picture story about the abandoned Hacienda Napoles, Escobar’s 3000-hectare estate in the Magdalena Valley. The TV news story shows Escobar’s former estate empty of life and falling into disrepair, Escobar’s prized car collection (including the one in which Al Capone was killed) turning to rust, the bullring filled with weeds, and the Colombian government, which has appropriated the property, unable to figure out what to do with it.

Hacienda Napoles, Pablo Escobar's estate. The single-engine plane over the entrance was the one Escobar used to start his business.

Over the billiard table during next few weeks, Yammara begins to learn a little more about Ricardo Laverde, who had been in jail for twenty years and has only recently been released, implying some reasons for his unusual curiosity about the current state of the Escobar property. Laverde offers no information, and Yammara does not press him. He does hear gossip, however, including the fact that “This man [Laverde] was not always this man. This man used to be another man.” He was also a pilot, information which fascinates Yammara, whose father and grandfather were also interesting in flying. After Laverde leaves for a trip that summer, Antonio Yammara’s own life begins to unfold for the reader. Living with one of his students, who is pregnant with his child, Yammara and Aura, his love, have their ultrasound on the day on which American Airlines Flight 965, flying from Miami to Cali, crashes into a mountain outside of Cali, introducing more airplane-related imagery which also affects Yammara – and, in a direct way, Laverde.

The remains of American Airlines Flight 965, which crashed into a mountain outside of Cali on December 29, 1995, killing someone close to Laverde and 158 other people.

Antonio Yammara’s relationship with Laverde is not altogether benign. When Laverde is eventually killed, something the reader discovers in the early pages, Yammara is inadvertently involved, and he suffers physically and emotionally for several years in the aftermath. His suffering involves every aspect of his existence, including his relationship with Aura and his young daughter Leticia. Eventually, Yammara meets Laverde’s daughter Maya and learns more about the parallel story of Laverde, his wife Elaine, and their own daughter. The time then flashes back to the 1970s, giving breadth to the themes and the philosophical ideas which the author illustrates throughout.

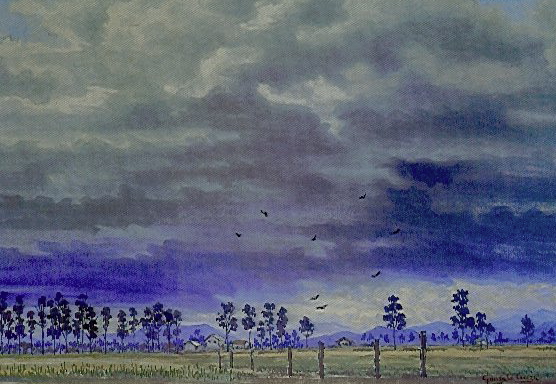

Eventually, Yammara goes to the Magdalena Valley to visit one of Laverde's family members and to find out more information about his life.

Throughout the thirty-year time span of the novel, author Vasquez keeps the novel moving forward. Virtually every image in the novel connects with similar images in other times, and as time passes, the reader comes to accept that “The great thing about Colombia [is] that nobody’s ever alone with their fate.” At the same time, few readers will be able to avoid feeling the isolation of the main characters as they deal with their issues alone in the face of overwhelming odds over which they have no control. No reader will “blame” Yammara for his choices, however bad the results are, since Vasquez excels at preparing the reader for those choices based on Yammara’s past history. And no reader will be able to avoid thinking of Laverde and his family as they deal with the long history of Colombia and its problems dealing with the country’s most lucrative export.

Yammara says the Magdalena Valley reminds him of a painting by Gonzalo Ariza, with its green plains, misty atmosphere, and gray mountains in the distance.

Exciting as a story and its development are, the novel also gives Vasquez ample opportunity to develop his themes. Yammara comments that “It’s always somewhat dreadful when someone reveals to us the chain that has turned us into what we are; it’s always disconcerting to discover, when it’s another person who brings us the revelation, the slight or complete lack of control we have over our own experience.” And when “the saddest thing that can happen to a person is to find that their memories are lies,” and that the best conclusion that one can draw about the motivation of someone close to us is simply, “He must have done something,” then the whole point of Vasquez’s novel is as clear, as “an object falling from the sky.”

Note: Translator Anne McLean maintains the honest and unpretentious language which the novel requires while also recreating vibrant images and well-wrought symbols. Her use of colloquial language allows the reader to feel involved with the speaker, despite the novel’s complex themes of life and death and fate.

Photos, in order: The authors photo appears on http://www.cancilleria.gov.co/

Hacienda Napoles, the enormous estate of Pablo Escobar in the Magdalena Valley, was left empty by the government which seized it, its zoo animals being left to fend for themselves. The hippos, which numbered four when Escobar purchased them, now number between sixty and seventy, living in the wild. Story here: http://www.bbc.com/ Photo of entrance, here: http://www.eluniversal.com.co/

The wreckage of the 1995 crash of American Airlines, Flight 967, outside of Cali, devastated Laverde. http://lessonslearned.faa.gov/

The Magdalena Valley, where Escobar’s estate was located, was also where a member of Laverde’s family lived. http://www.pbase.com/

Gustavo Ariza, who painted images of the Magdalena Valley, is an artist admired by Yammara. This painting is “Nuves de Lluvia.” http://blogs.elespectador.com