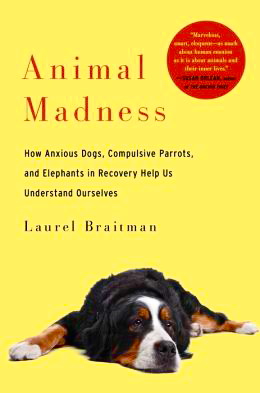

Note: Laurel Braitman is a Senior TED fellow. This book was one of Amazon’s Best Books of the Month for June and one of the Ten Best Books of the Week, this week, on Publishers Weekly.

“Mac, the miniature donkey…bats his eyelashes, angles his long furred ears toward you…and pushes his belly up against your thighs. Then, just as you’ve grown comfortable with his small stocky presence…something dark and confusing stirs within him. He stiffens, whips his head back, and bites down hard on the bony part of your shin and doesn’t let go…or he kicks his back legs like sharp springs in the direction of your kneecaps…You can’t predict when it will happen.”

Laurel Braitman introduces her research about the psychological traumas which animals can exhibit in this anecdote about Mac, a miniature donkey which she tended on the farm where she grew up. Mac’s mother had died just days after giving birth to him, and Laurel, then twelve, nursed him through his infancy. “I spent hours bottle-feeding him, and playing with him, until I got distracted by Anne of Green Gables books and my seventh-grade crush.” As a result, Mac, still a “child,” was weaned too quickly, she now believes, and then consigned to a corral without “a donkey mother to show him the ropes.” Suffering from a lack of nurturing and with no example of a healthy miniature donkey to follow, Mac turned on himself, biting off chunks of his fur and sometimes becoming unexpectedly violent against people and other animals.

Laurel Braitman introduces her research about the psychological traumas which animals can exhibit in this anecdote about Mac, a miniature donkey which she tended on the farm where she grew up. Mac’s mother had died just days after giving birth to him, and Laurel, then twelve, nursed him through his infancy. “I spent hours bottle-feeding him, and playing with him, until I got distracted by Anne of Green Gables books and my seventh-grade crush.” As a result, Mac, still a “child,” was weaned too quickly, she now believes, and then consigned to a corral without “a donkey mother to show him the ropes.” Suffering from a lack of nurturing and with no example of a healthy miniature donkey to follow, Mac turned on himself, biting off chunks of his fur and sometimes becoming unexpectedly violent against people and other animals.

This experience with Mac forever affected Braitman’s life. Now, more than twenty years later, Braitman has exhaustively studied the aberrant behavior of other disturbed animals, like Oliver, the four-year-old Bernese Mountain dog she and her husband adopted. Desperately in need of attention, Oliver received it, without restraint, from Laurel and her husband. Despite this, he still remained so anxious whenever he was left alone that he literally “went crazy,” snapping at flies that weren’t there and going into trances from which he could not be distracted. Eventually he even became a “liability at the dog park, [which] he had begun to approach…as a sort of canine buffet, the smallest Dachshunds and pugs like unattended snacks.” Ultimately, Oliver, alone one day and unable to cope, destroyed the framing on a 4th floor window in order to burst through the screen, falling fifty feet to the ground, but sustaining not a single broken bone. Separation anxiety was just the tip of the iceberg with Oliver, who becomes a recurrent image in the book.

From the outset Braitman recognizes that it is not possible to avoid completely the problem of “anthropomorphizing” (attributing human characteristics to things that are not human, like animals), but she says it is possible to “anthropomorphize well” if we can avoid “anthrocentrism,” the belief that we humans are unique in our abilities and that our intelligence is the only one that counts. Dogs and cats and elephants are not human, and they do not think and feel exactly as humans do since their daily lives are not similar. Still, all animals do share some basic characteristics and needs with other animals, and they are often subject to the same psychological problems as humans. Quoting scientists from around the world and tracing the evolution of thinking about animals over many generations, Braitman shows how our attitudes toward animals, from the ideas of Charles Darwin and Ivan Pavlov to contemporary animal behaviorists, primatologists, ethologists, zoologists, comparative psychologists, psychoanalysts, zookeepers and trainers have changed over the past two centuries, with the terminology for the animal problems they observed also changing.

Braitman uses her own experiences at animal sanctuaries, zoos, aquariums, water parks, and animal research centers throughout the world as rich resources in her study of psychologically impaired animals. Her own research, much of which is presented here, is thorough and academically rigorous enough to have earned her a PhD in the History of Science at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, but she also recognizes that the audience for this book is quite different from the academic audience to which she presented her original research. Here, her readers are primarily animal lovers interested in preventing the very real psychological problems which can develop within other, non-human animal species, and Braitman understands and hopes to assuage the emotions of guilt, helplessness, and sadness among pet lovers who have discovered that love is simply not enough in dealing with a disturbed animal. She considers herself among those who still deal with guilt about animals with whom they have lived.

Thanks to the research of animal behaviorists over the last hundred years, a “mad elephant,” a gorilla with “night terrors” and extreme “homesickness,” and a “brokenhearted” bear, may now be diagnosed with conditions more similar to some of the “codes of behavior” mentioned in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (1952) which identifies and names the psychiatric problems which humans face. Constantly being updated as more research evolves, this DSM is often used now to identify animal problems which resemble those of humans. Some of the same medications used to treat human problems are now being prescribed for animals with similar issues. PTSD, generalized anxiety disorders, separation anxiety, attachment disorders, generalized panic disorders, obsessive compulsive disorder, and even Alzheimer’s disease are all being diagnosed now in animals, and Braitman gives a wide variety of examples – from her research at an elephant park and at the Chiang Mai Zoo in Thailand, to her studies with animal behaviorists throughout the world, and her observations of abnormal behaviors among displaced animals at zoos, marine centers, and seaquariums across the United States. Enrichment programs for captive animals and even “family therapy” are now being used to help some of these animals which have not been able to deal with the reality of their current existence. Ultimately, Braitman questions whether some animals may even commit suicide, be it a dolphin’s “passive suicide” to the apparently deliberate stranding of many whales, sea lions, and monk seals.

Thanks to the research of animal behaviorists over the last hundred years, a “mad elephant,” a gorilla with “night terrors” and extreme “homesickness,” and a “brokenhearted” bear, may now be diagnosed with conditions more similar to some of the “codes of behavior” mentioned in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (1952) which identifies and names the psychiatric problems which humans face. Constantly being updated as more research evolves, this DSM is often used now to identify animal problems which resemble those of humans. Some of the same medications used to treat human problems are now being prescribed for animals with similar issues. PTSD, generalized anxiety disorders, separation anxiety, attachment disorders, generalized panic disorders, obsessive compulsive disorder, and even Alzheimer’s disease are all being diagnosed now in animals, and Braitman gives a wide variety of examples – from her research at an elephant park and at the Chiang Mai Zoo in Thailand, to her studies with animal behaviorists throughout the world, and her observations of abnormal behaviors among displaced animals at zoos, marine centers, and seaquariums across the United States. Enrichment programs for captive animals and even “family therapy” are now being used to help some of these animals which have not been able to deal with the reality of their current existence. Ultimately, Braitman questions whether some animals may even commit suicide, be it a dolphin’s “passive suicide” to the apparently deliberate stranding of many whales, sea lions, and monk seals.

Braitman observes a pilot whale and calf in Baja, Mexico, at Laguna San Ignacio. Mother and calf played beside the boat for an hour. Photo by Jodi Frediani

In her own life, Braitman admits that “I discovered that the guilty country is crowded. So many of us are there looking for answers and blaming ourselves, wondering what would have happened if we’d taken the dog to the park more often, refused to adopt the second cat that the first one despised, cleaned the iguana’s tank more frequently, given the hamster more time in his plastic ball, or ridden the horse as much as we had first intended. Animal madness isn’t our fault, though – not always anyway…”

Photos, in order: The author’s photo appears on her website: http://animalmadness.com

Braitman’s donkey Mac is from http://www.coolhunting.com/

Oliver’s photo and an interview with the author appear on http://www.coolhunting.com

Braitman and a baby elephant are on the author’s website: http://animalmadness.com/about/

In 2012, Braitman went to Baja, Mexico to observe pilot whale mothers and calves, who were very curious about her. The baby came right up to the boat. Photo by Jodi Frediani. http://www.ted.com/

ARC: Simon & Schuster

In this breakthrough novel, Lily King abandons the focus of her previous novels, which have always delved deeply into the subjects of love, family relationships, and personal identity within a narrow, circumscribed setting involving one major character. Her first book, The Pleasing Hour (2000), tells the story of an American au pair in Paris and her difficult relationships with the family for which she works. The English Teacher (2005) depicts a long-time teacher and her fifteen-year-old son who live on an island off the New England coast until the teacher accepts a marriage proposal, which changes all their lives. In

In this breakthrough novel, Lily King abandons the focus of her previous novels, which have always delved deeply into the subjects of love, family relationships, and personal identity within a narrow, circumscribed setting involving one major character. Her first book, The Pleasing Hour (2000), tells the story of an American au pair in Paris and her difficult relationships with the family for which she works. The English Teacher (2005) depicts a long-time teacher and her fifteen-year-old son who live on an island off the New England coast until the teacher accepts a marriage proposal, which changes all their lives. In

John Updike made the life of Boston’s suburban elite his territory—emphasizing their sense of entitlement and superiority, their “clubbiness,” their alcoholism, and their sexual experimentation as a way of asserting their existence and their privilege. One generation later, Lily King, like her fellow Massachusetts authors Susan and George Minot, shares her own insights into what sometimes passed for family life in a similar, privileged setting. Their fathers, as depicted by the younger authors, might have belonged to similar clubs, attended similar social events, and even drunk the same brand of gin. Their mothers were the rocks of the family, with values more closely allied with the real world, until their deaths or divorces left the children without a strong parental figure as they faced the storms of adolescence.

John Updike made the life of Boston’s suburban elite his territory—emphasizing their sense of entitlement and superiority, their “clubbiness,” their alcoholism, and their sexual experimentation as a way of asserting their existence and their privilege. One generation later, Lily King, like her fellow Massachusetts authors Susan and George Minot, shares her own insights into what sometimes passed for family life in a similar, privileged setting. Their fathers, as depicted by the younger authors, might have belonged to similar clubs, attended similar social events, and even drunk the same brand of gin. Their mothers were the rocks of the family, with values more closely allied with the real world, until their deaths or divorces left the children without a strong parental figure as they faced the storms of adolescence.

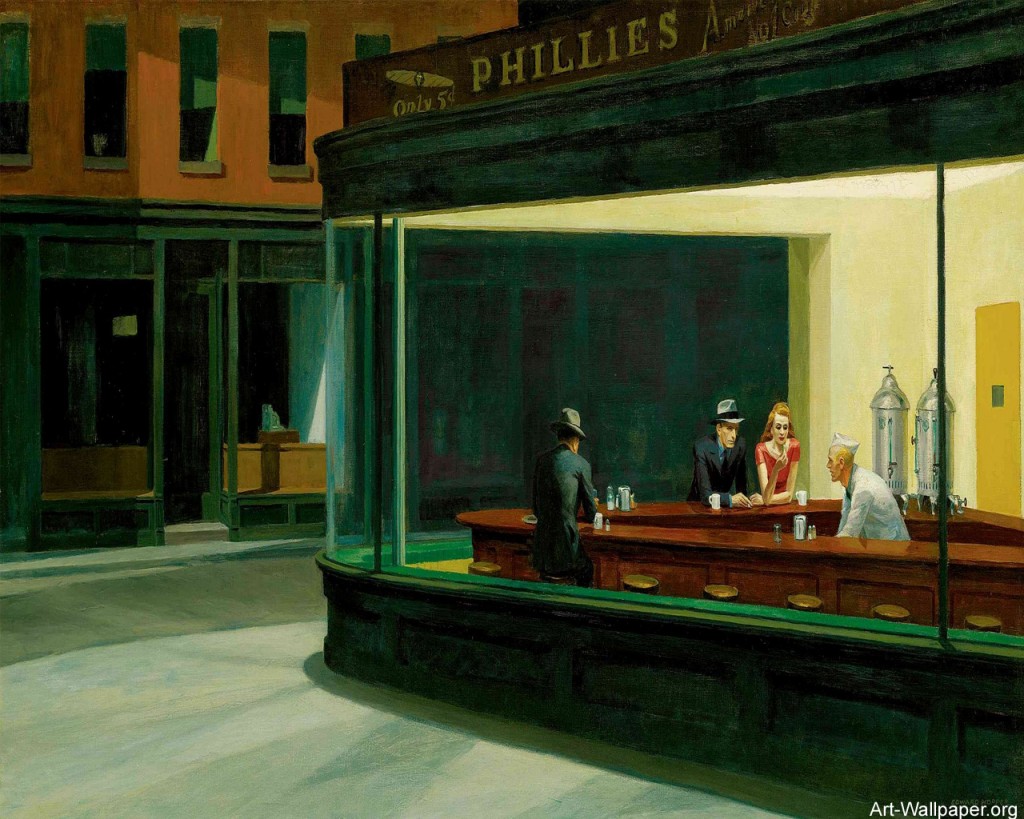

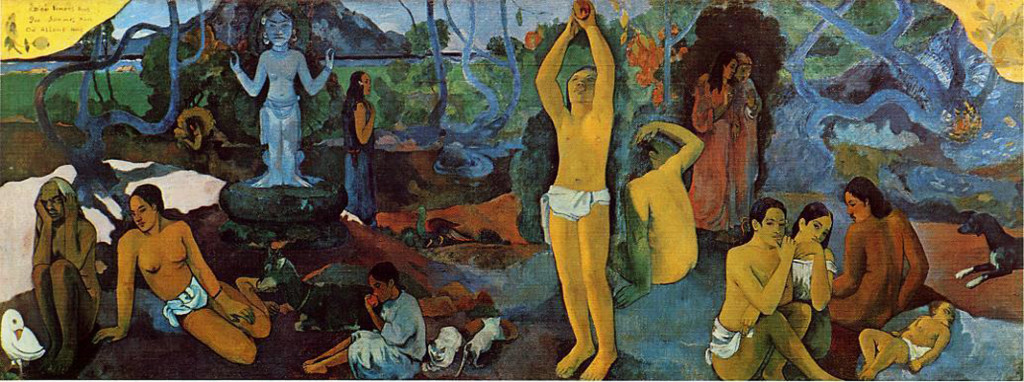

With his crisp, hard-boiled style, unrelenting pace, and a protagonist reminiscent of Travis McGee, whose earthiness was always mixed with a sense chivalric mission, Geoff Dyer might seem, at first, to have much in common with John D. MacDonald whose pulp novels of the 1960s and 1970s were so popular. Though Dyer does use a relatively tough and noir-ish style at the outset of the novel, and does have a main character with a mission, he quickly leaves the dark realism of MacDonald’s novels behind and moves into far more philosophical areas, alien to Travis McGee. Once beyond the first chapter, Dyer begins to reveal a more vibrant, less cryptic, literary style filled with unique images and descriptions. The plot abandons dark realism and starts moving in and out of reality, dreams, literature, symbolic stories reminiscent of old allegories, art, and medieval quests and jousts with an evil enemy, as Dyer branches out into metaphysical realms. No matter how surprising (and sometimes abstract) the author’s focus may seem to be as the novel progresses, however, Dyer never loses sight of his plot or his characters, and the overall framework of this quest novel never disappears.

With his crisp, hard-boiled style, unrelenting pace, and a protagonist reminiscent of Travis McGee, whose earthiness was always mixed with a sense chivalric mission, Geoff Dyer might seem, at first, to have much in common with John D. MacDonald whose pulp novels of the 1960s and 1970s were so popular. Though Dyer does use a relatively tough and noir-ish style at the outset of the novel, and does have a main character with a mission, he quickly leaves the dark realism of MacDonald’s novels behind and moves into far more philosophical areas, alien to Travis McGee. Once beyond the first chapter, Dyer begins to reveal a more vibrant, less cryptic, literary style filled with unique images and descriptions. The plot abandons dark realism and starts moving in and out of reality, dreams, literature, symbolic stories reminiscent of old allegories, art, and medieval quests and jousts with an evil enemy, as Dyer branches out into metaphysical realms. No matter how surprising (and sometimes abstract) the author’s focus may seem to be as the novel progresses, however, Dyer never loses sight of his plot or his characters, and the overall framework of this quest novel never disappears.