“People do not go to war, Nihil, they carry war inside them. Either they have the war within them or they don’t have it. The thing to think about is do you and I have war inside us?”—Mr. Niles to Nihil Herath

Living in an ethnically and religiously mixed neighborhood in Colombo, Sri Lanka, Nihil Herath is one of about a dozen children – Tamil, Sinhalese, Burgher, Hindu, Buddhist, Muslim, and Catholic – who take their cultural differences for granted. Nihil’s Sinhalese family is new to the neighborhood, but they fit in immediately with their neighbors, and under the leadership of Nihil’s mother, Savi Herath, they soon become the backbone of their little community. A teacher with a lot of experience, Mrs. Herath keeps her children and their friends active and busy, playing songs and encouraging their singing to her piano accompaniment, whether she, a Buddhist, is playing Christian hymns or the music from any of the other religions. A Sinhalese, Mrs. Herath has no hesitation about shopping in Tamil stores, even when her meddlesome next-door neighbor, Mrs. Silva, warns her against certain Tamil merchants. She invites Rose and Dolly Bolling, two neglected and ill-clothed Tamil children, to join her children for tea, and she eventually sees that they receive clothing that they need, without embarrassing them. Her goal is always to “do good,” though she does this instinctively and without moralizing.

Living in an ethnically and religiously mixed neighborhood in Colombo, Sri Lanka, Nihil Herath is one of about a dozen children – Tamil, Sinhalese, Burgher, Hindu, Buddhist, Muslim, and Catholic – who take their cultural differences for granted. Nihil’s Sinhalese family is new to the neighborhood, but they fit in immediately with their neighbors, and under the leadership of Nihil’s mother, Savi Herath, they soon become the backbone of their little community. A teacher with a lot of experience, Mrs. Herath keeps her children and their friends active and busy, playing songs and encouraging their singing to her piano accompaniment, whether she, a Buddhist, is playing Christian hymns or the music from any of the other religions. A Sinhalese, Mrs. Herath has no hesitation about shopping in Tamil stores, even when her meddlesome next-door neighbor, Mrs. Silva, warns her against certain Tamil merchants. She invites Rose and Dolly Bolling, two neglected and ill-clothed Tamil children, to join her children for tea, and she eventually sees that they receive clothing that they need, without embarrassing them. Her goal is always to “do good,” though she does this instinctively and without moralizing.

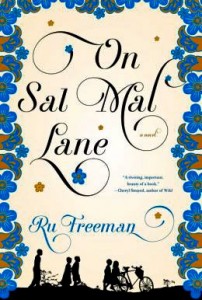

Using the Heraths and their four children – Suren (age 12), Rashmi (age 10), Nihil (age 9), and the energetic and irrepressible Devi (age 7) – as the linchpins of this saga of Sri Lanka, author Ru Freeman creates a lively neighborhood which represents virtually all the forces contesting for influence from 1979 – 1983, as the revolutionary Tamil Tigers decide to forego the legislative process and try to take over the country by force. Keeping the focus firmly on the children, who see and hear rumors of war, and the children’s fearful reactions to the increasingly dire news, Freeman creates a microcosm of the larger world and the devastation that is promised. Her characters, both the children and the adults who influence them, are lively and realistic, especially in their focus on the small, the personal, and the minutiae of everyday life as it begins to change.

Using the Heraths and their four children – Suren (age 12), Rashmi (age 10), Nihil (age 9), and the energetic and irrepressible Devi (age 7) – as the linchpins of this saga of Sri Lanka, author Ru Freeman creates a lively neighborhood which represents virtually all the forces contesting for influence from 1979 – 1983, as the revolutionary Tamil Tigers decide to forego the legislative process and try to take over the country by force. Keeping the focus firmly on the children, who see and hear rumors of war, and the children’s fearful reactions to the increasingly dire news, Freeman creates a microcosm of the larger world and the devastation that is promised. Her characters, both the children and the adults who influence them, are lively and realistic, especially in their focus on the small, the personal, and the minutiae of everyday life as it begins to change.

Much of the action surrounds Devi Herath, a seven-year-old with enough energy for ten people and little sense of fear, someone who scoots around befriending the friendless and including them in her world. For Raju Joseph, a thirty-five-year-old Tamil with physical and mental challenges, the Heraths are the first family which pays attention to him, and he is particularly drawn to young Devi. Sonna Bolling, a sad, fourteen-year-old whose father resents and often beats him, acts out as the neighborhood bully, but even he is drawn to the music he hears through the Heraths’ windows, and he wonders why there has never been music in his own life. Nihil Herath finds a thoughtful friend in old Mr. Niles, a bed-ridden Tamil man across the street who cannot help but think of Nihil as a son. Chaste childhood crushes begin to develop between some of the boys and girls, and their different ethnicities concern no one.

The simple little worlds of the children on Sal Mal Lane soon change dramatically: “The main road that abutted the lane marked a boundary beyond which lay a country where trouble was brewing. It was the sort of trouble that would soon overflow its banks and flood the nation, turning the small ponds of concern and occasional tears of Sal Mal Lane into their own tributaries of discontent.” A nation-wide strike, in which Mr. Herath is involved, fails, and eight thousand people lose their jobs. When the former prime minister is stripped of her civil rights, her left-leaning political party falls into disarray, and a new political majority arises, committed to different economic policies – “deprivation, privatization, theft of natural resources, and the end of self-sufficiency.” The author’s abrupt (and artificial) insertion of this information into the story prepares the reader for the disasters to come, even as the people of Sal Mal Lane themselves continue on with their normal lives, at least for a while.

Though the reader knows and expects certain results based on the historical background provided by the author, this information is not fully integrated into the novel’s story line, and the reader must wait for some time before important changes take place on the level of plot. It is not until riots finally break out in the poor neighborhoods across the main street from Sal Mal Lane that the historical background and the stories of the characters finally begin to coalesce. Though life goes on for the children, their innocent cricket matches and song-and-dance shows are set into sharp relief when seen in relation to the real life “shows” of riots, looting, and horrific fires. Within a day, the riots are everywhere, even on Sal Mal Lane.

The conclusion of this novel is dramatic, emotionally moving, and filled with insights as the aftereffects of the rioting are revealed, not only to the reader but to the participants themselves. Each family has had its own set of problems throughout the novel and has had to ensure the safety of its own members, but each family is also aware of the sometimes more difficult problems faced by their neighbors on the lane. All know that the rioters will target specific people because of their cultural and political loyalties, and the residents of Sal Mal Lane, accustomed to sharing their lives through celebrations and quarrels, must make difficult decisions during the crisis. It is not until the next day that everyone finds out the full extent of the devastation.

A Sri Lankan troop in 2008, twenty-five years after the setting of this novel, and one year before the end of the civil war.

The use of a child’s point of view is not one of my favorite techniques, but Freeman’s children are neither saccharine in their charm nor naïve to the point of silliness. Instead, they often behave intelligently, like small adults, dealing with some of the same problems as adults but often seeing them more clearly. They do not accept things at face value, and they often willingly seek help from adults whom they respect. Some children, like some adults, are victims, through no fault of their own. In this novel, the use of children allows Freeman to approach the complex issues of the war in Sri Lanka from a broad, but much simpler point of view than would have been possible with adult characters, and she takes full advantage of this technique, illuminating major themes about what it means to be human while obeying the old adage to “Keep Things Simple.”

Photos, in order: The author’s photo is from her website: http://rufreeman.com

The Sal Mal blossom and the blossoms of other flowering Sri Lankan trees may be found here: http://www.sightseeinglanka.lk

The happy hero of a local Sri Lankan youth match and his friends: http://news.bbc.co.uk/

The photo of the burned village is part of a story on the war in 2009: http://www.rnw.nl/

The Sri Lankan army troop is still fighting the Tamil Tigers in this photo from June, 2008, 25 years after the setting of this novel. Photo by EPA.

ARC: Graywolf