“Use me!” Miss Peycroft cried in ringing tones. “I am absolutely ready. Pure, so to speak, and unsullied, ready and waiting to be the heroine of your next novel.”–to Alma Porch, writer

Australian author Elizabeth Jolley completely won me over with Mr. Scobie’s Riddle (1983), a sad, funny, and wonderfully moving novel about the residents of a nursing home, and Miss Peabody’s Inheritance (1984), a delightful novel involving the lively correspondence between a popular Australian author and one of her admiring but repressed fans back in England. Because Jolley grew up in England and did not emigrate to Australia until 1959, when she was thirty-six, I have always associated her with my favorite British authors of the 1970s and 1980s—sly and subtle female writers like Muriel Spark, Jane Gardam, Barbara Pym, Penelope Lively, Alice Thomas Ellis, and Beryl Bainbridge, who did not hesitate to use satire to bring down the pompous, while also creating memorable characters whose often humorous dialogue brings them to life on the page. Products of their time and setting, these authors could skewer their characters’ social pretensions with the literary equivalent of a penknife, rather than a rapier, while maintaining a “lady-like” demeanor of innocence. Not surprisingly, Bainbridge, Lively, and Spark were all honored by the Queen and became Dame Commanders of the British Empire. In addition, Gardam has been honored as an Officer of the Order of the British Empire, while Ellis and Pym were elected Fellows of the Royal Society of Literature. All have won numerous literary prizes.

Australian author Elizabeth Jolley completely won me over with Mr. Scobie’s Riddle (1983), a sad, funny, and wonderfully moving novel about the residents of a nursing home, and Miss Peabody’s Inheritance (1984), a delightful novel involving the lively correspondence between a popular Australian author and one of her admiring but repressed fans back in England. Because Jolley grew up in England and did not emigrate to Australia until 1959, when she was thirty-six, I have always associated her with my favorite British authors of the 1970s and 1980s—sly and subtle female writers like Muriel Spark, Jane Gardam, Barbara Pym, Penelope Lively, Alice Thomas Ellis, and Beryl Bainbridge, who did not hesitate to use satire to bring down the pompous, while also creating memorable characters whose often humorous dialogue brings them to life on the page. Products of their time and setting, these authors could skewer their characters’ social pretensions with the literary equivalent of a penknife, rather than a rapier, while maintaining a “lady-like” demeanor of innocence. Not surprisingly, Bainbridge, Lively, and Spark were all honored by the Queen and became Dame Commanders of the British Empire. In addition, Gardam has been honored as an Officer of the Order of the British Empire, while Ellis and Pym were elected Fellows of the Royal Society of Literature. All have won numerous literary prizes.

The earlier books that I have read by Jolley, while a bit more boisterous in some ways than the works of her contemporaries in England during the period, seem to fit comfortably into the niche occupied by these other, better known authors, despite Jolley’s unconventional (and some might say outrageous) private life. With Foxybaby (1985), which follows Mr. Scobie (1983) and Miss Peabody (1984), however, Jolley permanently separates herself from her peers back in England, writing a book in which nothing is sacred, with characters who are sometimes crazy, usually self-absorbed, unashamedly earthy, and often bawdy. She is realistic – and enthusiastic – in her depiction of sex in all its variations as salve for the souls of the lonely and the sometimes bored. Nothing about this book is dainty or subtle.

The earlier books that I have read by Jolley, while a bit more boisterous in some ways than the works of her contemporaries in England during the period, seem to fit comfortably into the niche occupied by these other, better known authors, despite Jolley’s unconventional (and some might say outrageous) private life. With Foxybaby (1985), which follows Mr. Scobie (1983) and Miss Peabody (1984), however, Jolley permanently separates herself from her peers back in England, writing a book in which nothing is sacred, with characters who are sometimes crazy, usually self-absorbed, unashamedly earthy, and often bawdy. She is realistic – and enthusiastic – in her depiction of sex in all its variations as salve for the souls of the lonely and the sometimes bored. Nothing about this book is dainty or subtle.

The novel opens with Miss Alma Porch, a timid teacher and writer at a girls’ school, writing to Miss Josephine Peycroft, the Principal at Trinity College, located in a remote area of western Australia, about a summer job. The principal has hired Porch to conduct a drama program which will be part of the session to build a “Better Body Through the Arts.” On her way to Trinity, however,Porch is involved in a car crash which leaves her car and two others in need of substantial repairs. She is not reassured when she overhears the conveniently parked tow truck operator tell a companion, “We’re in business. I’m telling you, three cars orf to the smash yard just in one trip, not three trips but one. Yo’ll get your share never youse worry.”

Wheat fields lining both sides of the road were the only scenery for Porch as she traveled west to Trinity College.

Her arrival at the school itself also has ominous overtones. Miss Peycroft has her own ideas of the manner in which she wants Porch’s play to be produced “by the students,” and she demands that Mrs. Viggars, a well-off return visitor, be the lead player. Porch’s first vision of Mrs. Viggars is in a photo from the previous year in which Viggars, in a course called “Basic Self Expression,” is shown sitting in a refrigerator-sized box with a cushion on her head, rocking her way across the courtyard. As the other participants arrive, two of them being gorgeous young men brought by a former participant, it becomes clear to everyone except Porch that these additional participants are there to provide nightly “fun and games” for the people who brought them, and perhaps for each other. Porch is already aware from conversations which have taken place under her bedroom window, that the tow truck operator Miles, his wife, and another woman are already having a great deal of extracurricular fun, chasing each other around the grounds. Openly lesbian and gay relationships abound, and assignations of all kinds occur at any time and place. Throughout the novel, it is Porch who seems to be left out, though she often overhears her companions’ suggestive conversations and is frequently trapped so that she cannot escape participating in these events vicariously.

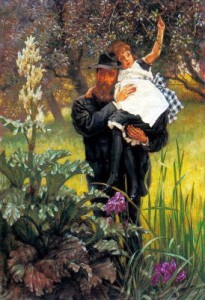

The play, “Foxybaby,” for which Porch has brought the requisite props, raises many issues which obviously parallel those of the participants in the program, the primary themes being the relationship between alienation, loneliness, and lack of love. The play’s lead character, Mr. Steadman, a scholar and writer, is waiting outside a cafe for his daughter Sandy to leave and go home with him, as the play opens. Sandy, “Foxybaby,” is recently released from prison. She has just had a baby, and is suffering from drug addiction. Her child is also infected and addicted – and not thriving. The action, as Porch develops it, is accompanied by punk rock and disco music, though Peycroft keeps trying to change it. The relationship between father (Steadman), daughter, and granddaughter reveals itself as the play continues. Predictable complications arise. (Obviously, this play is not going to be a candidate for any Tony Awards.)

The play, “Foxybaby,” for which Porch has brought the requisite props, raises many issues which obviously parallel those of the participants in the program, the primary themes being the relationship between alienation, loneliness, and lack of love. The play’s lead character, Mr. Steadman, a scholar and writer, is waiting outside a cafe for his daughter Sandy to leave and go home with him, as the play opens. Sandy, “Foxybaby,” is recently released from prison. She has just had a baby, and is suffering from drug addiction. Her child is also infected and addicted – and not thriving. The action, as Porch develops it, is accompanied by punk rock and disco music, though Peycroft keeps trying to change it. The relationship between father (Steadman), daughter, and granddaughter reveals itself as the play continues. Predictable complications arise. (Obviously, this play is not going to be a candidate for any Tony Awards.)

"The Widower," by James Jacques Joseph Tissot, a painting which Mrs. Viggars suggests represents what Steadman is facing--dependence, need, sorrow, protection, and possession.

Elizabeth Jolley is obviously having great fun taking advantage of the freer, more forgiving attitudes of Australia as she creates this over-the-top novel, filled with wild characters – some, like Porch, exceedingly repressed, and some like Mrs. Viggars and Miss Harrow, taking part in a summer program in the boonies where they have little else to do except pursue their desires in a safe atmosphere, away from civilization. Jolley’s large cast of characters is well-choreographed to allow their farcical actions to proceed in many different directions at once, though the novel’s focus and themes sometimes get lost in the confusion. The ironies of the “Foxybaby” play, with its strange and sexual subtexts, stereotyped characters, and clichéd action, are frequently matched satirically with quotations from real literary sources – Sophocles, Goethe, Proverbs, Jon Dryden, Ibsen, Schopenhauer – to provide “breadth” and “depth” to the action. Ultimately, the novel connects the action in Porch’s play with real life, and this is where everything spins wildly, and some might say, quite happily, out of control.

ALSO by Elizabeth Jolley: MR. SCOBIE’S RIDDLE and MISS PEABODY’S INHERITANCE

Photos, in order: The author’s photo is from http://www.heraldsun.com.au

The Western Australia wheatfield may be found on http://markosun.wordpress.com

Alma Porch brought her fox stole with her for the play, “Foxybaby.” http://www.osfcostumerentals.org

James Jacques Joseph Tissot’s “The Widower,” painted in 1876, is symbolic of some of the action in Alma’s play. http://www.amazon.com