Note: Elizabeth Jolley was WINNER of both the Age Book of the Year Award and the Western Australian Premier’s Book Award in 1983 for this novel.

“His thoughts were of leaving [the nursing home] and of the place he wanted to go back to. It was his favorite thought and it consoled him. Slowly he allowed himself to think of the small house tucked away on a slope, partly in the shade of a row of pine trees planted by himself…He paused, in his thoughts, at the delicious moment of opening the door. He stretched out his hand…thinking about his rooms on the other side of the door.”—Mr. Scobie, at the nursing home.

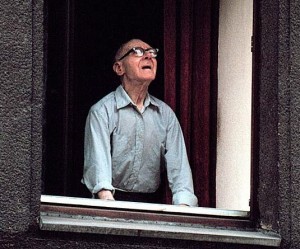

Martin Scobie, David Hughes, and Fred Privett, all age eighty-five, have just been admitted to the nursing home of St. Christopher and St. Jude following the bizarre crash of their three ambulances at the intersection in front of the facility. Admitted for their recuperation, they must share a small single room in which the light switch can only be reached by leaning across one of the beds. Some furniture has been removed to accommodate the extra beds, and the wardrobe, blocking a window, is inaccessible because of the third bed. Even if they had a view through that window, however, their accommodations would not be much improved. “Immediately outside the window was a mass of dusty green foliage of the kind which grows outside kitchens and hotel toilets…The leaves, moving in endless trembling toward and away from one another, gave an impression of trying to speak or to listen but always turning away before any tiny message could either be given or heard,” a detail emblematic of all life at this nursing home, which “specializes” in non-communication, not just between staff and patients, but between staff and each other, and among the patients themselves.

Martin Scobie, David Hughes, and Fred Privett, all age eighty-five, have just been admitted to the nursing home of St. Christopher and St. Jude following the bizarre crash of their three ambulances at the intersection in front of the facility. Admitted for their recuperation, they must share a small single room in which the light switch can only be reached by leaning across one of the beds. Some furniture has been removed to accommodate the extra beds, and the wardrobe, blocking a window, is inaccessible because of the third bed. Even if they had a view through that window, however, their accommodations would not be much improved. “Immediately outside the window was a mass of dusty green foliage of the kind which grows outside kitchens and hotel toilets…The leaves, moving in endless trembling toward and away from one another, gave an impression of trying to speak or to listen but always turning away before any tiny message could either be given or heard,” a detail emblematic of all life at this nursing home, which “specializes” in non-communication, not just between staff and patients, but between staff and each other, and among the patients themselves.

As Australian author Elizabeth Jolley develops this relentlessly dark-humored and totally absorbing novel, she also displays enormous talent for developing sensitive character sketches of the elderly patients. All seem to be “nice,” even “sweet,” people, perhaps like our parents or grandparents, and though they may be a bit confused with all the changes in their lives which the nursing home has generated, a reader would need a heart of granite not to share their desires that they return home where they “belong.” Mr. Hughes, for example, partly paralyzed, “kept wanting to say he was sorry because of all the things which had to be done for him.” Mr. Privett is a bit ditsy and repeats conversations he has had with his pet duck, Hep, whom he believes is “drunk” because she is brooding on a nest with fifteen eggs. He audibly reminds his pet chicken Hildegarde, that she is a “meat bird,” and all he wants is to get back to the poultry shed so he can enjoy a daily smoke with his birds. Mr. Scobie loves his old house and the sounds of the breeze, and as he muses about it, he now wishes he had also explored the hill behind it. A Bible scholar and lover of classical music, Mr. Scobie’s only potential pleasure at the nursing home is through the recordings he has brought with him.

Unfortunately, it appears that the deck is stacked against all of these people and the other residents of the home. Some critics have even suggested that this novel is reminiscent of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. Though several of the old-timers do get up in the middle of the night to play raucous, cut-throat card games in Room 3, just down the hall from Mr. Scobie and the others in Room 1, the games are not fraught with the kind of horror one sees in Cuckoo’s Nest. Lt. Col. Price, the brother of Matron Hyacinth Price, always loses “big” at those card games, but there seem to be few penalties for losing. The home and the staff, however insensitive they may be, are far from being psychopaths like Nurse Ratched. Though the Matron herself does demand total allegiance, and is unsympathetic and clearly determined to get each of the patients to put all his/her money into the home’s accounts (to make life “easier” for them), she is neither as intelligent nor as evil as Nurse Ratched.

Unfortunately, it appears that the deck is stacked against all of these people and the other residents of the home. Some critics have even suggested that this novel is reminiscent of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. Though several of the old-timers do get up in the middle of the night to play raucous, cut-throat card games in Room 3, just down the hall from Mr. Scobie and the others in Room 1, the games are not fraught with the kind of horror one sees in Cuckoo’s Nest. Lt. Col. Price, the brother of Matron Hyacinth Price, always loses “big” at those card games, but there seem to be few penalties for losing. The home and the staff, however insensitive they may be, are far from being psychopaths like Nurse Ratched. Though the Matron herself does demand total allegiance, and is unsympathetic and clearly determined to get each of the patients to put all his/her money into the home’s accounts (to make life “easier” for them), she is neither as intelligent nor as evil as Nurse Ratched.

The patients are obviously never going to get back home, something the reader knows from the beginning, yet one cannot help but hope, as various characters take off on their own to try to find their way home, that one or two of them will succeed. Even if Matron Price does not get their property, however, they still lose – their heirs are already in charge. It is only a question of waiting for the narrative to develop to find out what the younger generation plans to do with the beloved “homes” of their hospitalized relatives.

As time passes, and the local choir ladies and little children come to the home to sing Christmas carols, the patients reveal what an ordeal this kind of visit is for them. As they “[feel] with old hands along the unfamiliar wall” to the gathering place for the concert, they each think of home and their own deceased relatives, the lovely family celebrations, and  good times, but as their memories come flooding back and become all-important to them, the patients, unfortunately, have no one to share these with. Each lives in his own world, and the nursing home itself increases the sense of impersonality and dehumanization by not allowing anyone to use first names in address or conversation. Mr. Scobie does not even enjoy his music anymore, and as he remembers the images which used to be inspired by the music, he also remembers that in his younger, healthier days, he had thought that he “would preserve images of rapture somewhere inside him for those times ahead when he would need to be comforted.” But now, here at St. Christopher and St. Jude, where he needs to be comforted, “there’s no dignity…the only memories existing for him were the sad and painful. He could not recall anything from those treasures he once thought he was putting away safely for later.”

good times, but as their memories come flooding back and become all-important to them, the patients, unfortunately, have no one to share these with. Each lives in his own world, and the nursing home itself increases the sense of impersonality and dehumanization by not allowing anyone to use first names in address or conversation. Mr. Scobie does not even enjoy his music anymore, and as he remembers the images which used to be inspired by the music, he also remembers that in his younger, healthier days, he had thought that he “would preserve images of rapture somewhere inside him for those times ahead when he would need to be comforted.” But now, here at St. Christopher and St. Jude, where he needs to be comforted, “there’s no dignity…the only memories existing for him were the sad and painful. He could not recall anything from those treasures he once thought he was putting away safely for later.”

Elizabeth Jolley’s descriptions and her lively and psychologically revealing scenes are both ironic and often very funny, despite their dark edges and the novel’s pervading sadness. An undercurrent of sexuality runs through the novel, and ever so slowly, as she lets her characters hark back to events in their pasts, the sympathetic reader is jolted by sudden recognitions, suggesting some of the reasons these “nice,” “sweet” characters may be in the nursing home. The  suggestions remain suggestions, however, with alternative explanations for behavior still possible, and as some characters pass away, the transience of life, and even more importantly, the transience of their memories raise inescapable questions for the reader regarding his/her own life. Jolley is a world class author, capable of creating serious questions and developing the biggest of the world’s themes within small settings and scenes, and I can hardly wait to read the next book being released, MISS PEABODY’S INHERITANCE. Persea Books has announced its intention to release in the US all of Elizabeth Jolley’s works, and I will be first in line! She is a new Favorite!

suggestions remain suggestions, however, with alternative explanations for behavior still possible, and as some characters pass away, the transience of life, and even more importantly, the transience of their memories raise inescapable questions for the reader regarding his/her own life. Jolley is a world class author, capable of creating serious questions and developing the biggest of the world’s themes within small settings and scenes, and I can hardly wait to read the next book being released, MISS PEABODY’S INHERITANCE. Persea Books has announced its intention to release in the US all of Elizabeth Jolley’s works, and I will be first in line! She is a new Favorite!

ALSO by Jolley: MISS PEABODY’S INHERITANCE and FOXYBABY

Photos, in order: The author’s photo shows Elizabeth Jolley upon receiving honorary doctorate from Curtin University of Technology in Australia. http://john.curtin.edu.au

The photo of the elderly man at the window, by Mihai Molceanu, is from http://www.medievaltours.com

The recently demolished house, similar to that faced by one of the characters here, is from http://www.silverspringscommunity.com

An old man walks along the railroad tracks, as did one of the men here. Photo by Christopher Elwell: http://fineartamerica.com

Patients gamble in the facility at night. From http://www.emuleday.com

ARC: Persea Books