“It wasn’t me who turned everything upside down. It was Dostoevsky!”—says Rassoul, the protagonist of this novel.

“Stop going on about your precious Dosto—whatever! You didn’t kill because you’d read his book. You read it because you wanted to kill. That’s all. If he were still alive, he would accuse you of plagiarism!”—Old clerk, interviewing Rassoul.

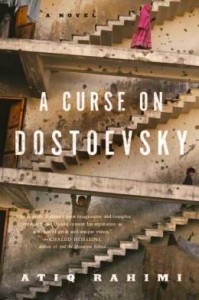

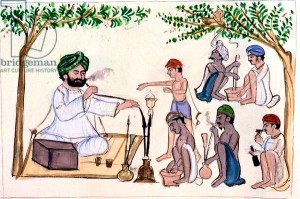

In this ironic and absurd quotation suggesting some of the many parallels between the action in this novel and that in Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment, author Atiq Rahimi focuses on the psychological state of mind of Rassoul, an Afghan student who studied for years in St. Petersburg, Russia, like Raskolnikov in Crime and Punishment, before returning to his home in Kabul, a city occupied by the Russians and their army from 1979 -1989. For Rassoul, whose very name suggests his similarities to Raskolnikov, Kabul in the 1980s bears no resemblance to the exciting, intellectual, and independent city it was a generation earlier. The city itself is now devastated, its educated citizens now unable to work in any meaningful job, and no one is sure of who is really in charge – the Russians, the Muslim mujahideen, the Afghan communists (like his father), or those seeking independence from all these competing interests. What is certain is that none of the ordinary citizens have any money, all are hungry and cold, and the only escape – at least for Rassoul and his friends – is to be found at the saqi-khana, where a plethora of drugs offers them temporary respite.

In this ironic and absurd quotation suggesting some of the many parallels between the action in this novel and that in Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment, author Atiq Rahimi focuses on the psychological state of mind of Rassoul, an Afghan student who studied for years in St. Petersburg, Russia, like Raskolnikov in Crime and Punishment, before returning to his home in Kabul, a city occupied by the Russians and their army from 1979 -1989. For Rassoul, whose very name suggests his similarities to Raskolnikov, Kabul in the 1980s bears no resemblance to the exciting, intellectual, and independent city it was a generation earlier. The city itself is now devastated, its educated citizens now unable to work in any meaningful job, and no one is sure of who is really in charge – the Russians, the Muslim mujahideen, the Afghan communists (like his father), or those seeking independence from all these competing interests. What is certain is that none of the ordinary citizens have any money, all are hungry and cold, and the only escape – at least for Rassoul and his friends – is to be found at the saqi-khana, where a plethora of drugs offers them temporary respite.

As the book opens, Rassoul has just killed an old woman with an axe. Though he is reluctant to take her jewelry and money, he finally decides to take only the cash, but, ironically, no matter how hard he tries, he is unable to pry the wad of bills out of the dead woman’s grip. When he hears someone calling her name, “Nana Alia,” he escapes, not knowing who the “intruder” is, and blaming Dostoevsky for “stopping me from…killing a second woman, this one innocent…and becoming prey to my remorse, sinking into an abyss of guilt, [and] ending up sentenced to hard labour…” Calling himself “a pathetic excuse for a murderer,” he notes that he has “blood on [his] hands, but nothing in [his] pockets.” His mother, sister, and fiancée, whom he cannot marry without money, have all depended upon him, and he has failed to provide for their future.

Burkha shop. Photo by Reuters, Mohammad Shoiab, 2009, in Afghanistan. See photo credits for more information.

When he waits, watching to see who has come to the old woman’s house just after her death, he sees a woman in a “sky-blue chador” leaving the house and rushing away, but he has difficulty catching up with her, and when he finally meets her eyes “through the gauze of her chador,” he does not recognize her. Later, when he wants to check on the old woman’s body, he learns that there is no body. The person he killed has vanished. Like Raskolnikov, he returns to his own house, notes his crime, and then falls into feverish sleep. When he wakes up, he cannot speak, except through writing.

His additional problems with his landlord, to whom he owes rent, add to his woes, and as his friends reflect the competing beliefs which are tearing the country apart, he learns with horror of his beloved Sophia’s predicament regarding her family and their problems paying their rent. His health, never strong, begins to fail, his mind wanders, he is unable to make decisions, and the doctor he finally decides to see tells him he must relive whatever emotional situation is causing his loss of voice, a prescription which infuriates him and increases his terror regarding the future. Flashbacks of his past in the years before the Russians haunt him.

Liquor Shop (Saqi-Khana) c.1890 (w/c on paper), Punjabi School, (19th century) / © Royal Asiatic Society, London, UK / The Bridgeman Art Library

Through Rassoul’s diary, the author reveals Rassoul’s life as a young man in Mazar-e-Sharif; his love for Sophia; the corruption of those in power, one of whom has made money by selling items from the National Archives; the murders that occur as one group takes over power and retaliates against members of other groups, making them “pay” for their “crimes”; and the bombing and shelling in the city which the Russians now “control.” Real accounts alternate with nightmares and fever dreams, which torment Rassoul, and when two men from the Ministry of Information and Culture come to interview him and ask him which “side” he is on, he can only write, “None.”

Atiq Rahimi, who emigrated from Afghanistan to France when he was in his twenties, speaks throughout the novel with the authority of someone who has lived through the traumas of his main characters, a characteristic which also pervades an earlier novel, Earth and Ashes. Modeling this novel on Crime and Punishment, widely read by westerners, Rahimi shows the universality of the horrors and the psychological traumas created by a sense of guilt in a character from Kabul, at least as intense as that of Raskolnikov from the culturally more familiar St. Petersburg. Raskolnikov’s crime was personal, and the punishment that he both seeks and rejects, while philosophically complex, is more personal than the crime of Rassoul. Rassoul’s crime grows out of the chaos in Kabul in the 1980s, in which ordinary people do not know who is in charge from day to day, or which “philosophy” provides the moral compass, if any, for its leaders.

The intense and dramatic circumstances under which Rassoul must finally come to terms with his crime in the context of the Kabul of his day provides an absurd coda to his personal travails. “I want my death to be a sacrifice,” he says. “My trial will be on behalf of all war criminals: communists, warlords, mercenaries….” His interrogator is not interested. “Stop thinking you are that Dostoevky character, please. His act only made sense within the context of his society, his religion,” he says ironically. As Rassoul is left to make sense of his actions and their results, the reader is forced to consider how much free will a character like Rassoul has when trying to save lives in the context of war and the chaos which accompanies it. Ultimately, Rassoul is forced to consider whether he is the victim of his own crime, or whether, in fact, “Even the flies are singing for [him].”

ALSO by Atiq Rahimi: EARTH AND ASHES

Photos, in order: The author’s photo by Bertrand Guay at Agence France-Presse appears here: http://www.ledevoir.com/

Throughout, the author and translator make no distinction between the full burkha and the “sky-blue chador,” which a woman was wearing when she left the building where Nana Alia was killed. The character in “sky-blue chador” in the novel, which took place in the 1980s, supposedly looked at Rassoul “through the gauze of her chador,” which implies the full burhka and not the simple chador head covering which shows the woman’s entire face. http://www.reuters.com/

The watercolor of the Liquor Shop (Saqi-Khana) c.1890 (w/c on paper), Punjabi School, (19th century) / © Royal Asiatic Society, London, UK / The Bridgeman Art Library, may be found here: http://www.bridgemanart.com/ Rassoul and his friends spent much time at the local saqi-khana escaping from the traumas of their lives.

The photo of the Shah-e do Shamshira Wali Mosque where Sophia ran afoul of the authorities is from http://en.wikipedia.org/

The Zarnegar Park in Kabul, in the 1970s, is found on http://afghanistanonmymind.blogspot.com

The remains of the rose garden in the same Zarnegar Park in 2009 are shown on http://afghanistanonmymind.blogspot.com/

ARC: Other Press

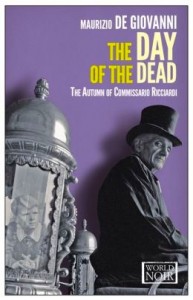

When the body of a thin little orphan, guarded by a small dog, is discovered in an alcove at the base of the Tondo di Capodimonte staircase in Naples, Commissario Luigi Alfredo Ricciardi di Malomonte is on the case. It is 1930, and Naples is preparing for the imminent arrival of Il Duce, Benito Mussolini, Italy’s ruler. It would not do for Naples to appear to be anything other than the perfect fascist city – a city with no crime – when Il Duce (pejoratively referred to here as “Thunder Jaw”) makes his appearance, and the powers in charge of security want no complications. Commissario Ricciardi, investigating this case, possesses a kind of extrasensory perception regarding death. If he appears at the location of a violent death and has a moment to communicate with the body, he is able to hear the victim’s last cryptic thought. By concentrating on possible hidden meanings revealed in this thought, he and Brigadier Maione, his only friend, gain important clues to understanding the victim’s last moment. In this case, however, no ghostly image appears and no last words are discernable when Ricciardi communes with the boy’s body, and he does not understand why.

When the body of a thin little orphan, guarded by a small dog, is discovered in an alcove at the base of the Tondo di Capodimonte staircase in Naples, Commissario Luigi Alfredo Ricciardi di Malomonte is on the case. It is 1930, and Naples is preparing for the imminent arrival of Il Duce, Benito Mussolini, Italy’s ruler. It would not do for Naples to appear to be anything other than the perfect fascist city – a city with no crime – when Il Duce (pejoratively referred to here as “Thunder Jaw”) makes his appearance, and the powers in charge of security want no complications. Commissario Ricciardi, investigating this case, possesses a kind of extrasensory perception regarding death. If he appears at the location of a violent death and has a moment to communicate with the body, he is able to hear the victim’s last cryptic thought. By concentrating on possible hidden meanings revealed in this thought, he and Brigadier Maione, his only friend, gain important clues to understanding the victim’s last moment. In this case, however, no ghostly image appears and no last words are discernable when Ricciardi communes with the boy’s body, and he does not understand why.

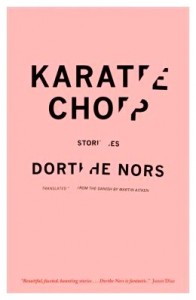

Strange and twisted characters, the vivid but often sinister lives they inhabit in their imaginations, and their almost universal preoccupation with death make this collection of short stories compelling, even mesmerizing, despite the sense of menace lurking within each story. The characters all appear on the surface to be “just like us,” ordinary people with similar sensibilities and familiar goals for the future, but as they develop during the fifteen unusually short stories in this collection, Danish author Dorthe Nors slowly and subtly reveals how off-kilter they really are. Virtually all these characters are lonely and unloved, craving companionship, if not a lover, and they depend on their imaginations to provide the excitement which is missing from their real lives. Most them, however, do not recognize that there is a fine line between their harmless daydreams and the nightmarish visions which sometimes threaten their equilibrium and control their actions.

Strange and twisted characters, the vivid but often sinister lives they inhabit in their imaginations, and their almost universal preoccupation with death make this collection of short stories compelling, even mesmerizing, despite the sense of menace lurking within each story. The characters all appear on the surface to be “just like us,” ordinary people with similar sensibilities and familiar goals for the future, but as they develop during the fifteen unusually short stories in this collection, Danish author Dorthe Nors slowly and subtly reveals how off-kilter they really are. Virtually all these characters are lonely and unloved, craving companionship, if not a lover, and they depend on their imaginations to provide the excitement which is missing from their real lives. Most them, however, do not recognize that there is a fine line between their harmless daydreams and the nightmarish visions which sometimes threaten their equilibrium and control their actions.

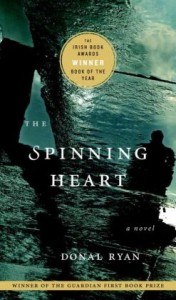

Though he is one of the best-liked and most admired young men in the small rural village in which he lives, Bobby Mahon hates his father, and the feeling appears to be mutual. Still, he visits him every day at his cottage just beyond the weir – “to see is he dead and every day he lets me down…He stays alive to spite me.” Bobby fears that his father will soon learn that Bobby, like the other employees of Pokey Burke, has been out of work for two months now, having lost everything in the financial troubles that hit Ireland after the economic “bubble” collapsed in 2007. To make things even worse, Pokey has absconded with all the funds that his employees had contributed for their pensions, and Bobby believes that “if [my father] ever finds out how Pokey Burke shafted me, he’ll surely make a full recovery. Pokey could apply to be beatified then having had a miracle ascribed to him.” In the meantime, Bobby dreams of killing his father: “It wouldn’t be murder anyway, just putting the skids under nature. It’s only badness that sustains him.”

Though he is one of the best-liked and most admired young men in the small rural village in which he lives, Bobby Mahon hates his father, and the feeling appears to be mutual. Still, he visits him every day at his cottage just beyond the weir – “to see is he dead and every day he lets me down…He stays alive to spite me.” Bobby fears that his father will soon learn that Bobby, like the other employees of Pokey Burke, has been out of work for two months now, having lost everything in the financial troubles that hit Ireland after the economic “bubble” collapsed in 2007. To make things even worse, Pokey has absconded with all the funds that his employees had contributed for their pensions, and Bobby believes that “if [my father] ever finds out how Pokey Burke shafted me, he’ll surely make a full recovery. Pokey could apply to be beatified then having had a miracle ascribed to him.” In the meantime, Bobby dreams of killing his father: “It wouldn’t be murder anyway, just putting the skids under nature. It’s only badness that sustains him.”

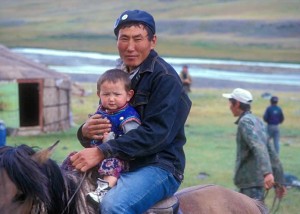

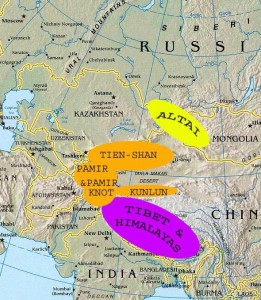

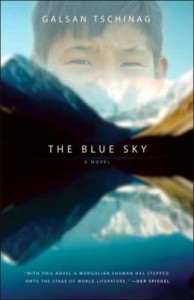

With a casual and natural curiosity about the mysteries of life, a young Tuvan boy from Mongolia muses about dreams in this quotation from The Blue Sky, clearly illustrating the aspects of this autobiographical novel which make it come alive so vibrantly for those of us who know nothing about his culture and are learning about it for the first time. Set in the 1940s, the novel recreates a time in which the old ways are the only ways for the Tuvan people, an isolated group of nomadic people living in the Altai Mountains of Mongolia on the Russian border. Using the point of view of Dshurukuwaa, the young Tuvan boy, the author tells a coming-of-age story which is clearly his personal story, as he observes the growth of the outside influences which are just beginning to affect his people. The boy is very much a little boy, always acting “in the minute,” reacting to daily events with all the passion of a child, and the author, Galsan Tschinag, is able to communicate the boy’s feelings to a foreign audience in ways which make the Tuvan culture both understandable and unforgettable.

With a casual and natural curiosity about the mysteries of life, a young Tuvan boy from Mongolia muses about dreams in this quotation from The Blue Sky, clearly illustrating the aspects of this autobiographical novel which make it come alive so vibrantly for those of us who know nothing about his culture and are learning about it for the first time. Set in the 1940s, the novel recreates a time in which the old ways are the only ways for the Tuvan people, an isolated group of nomadic people living in the Altai Mountains of Mongolia on the Russian border. Using the point of view of Dshurukuwaa, the young Tuvan boy, the author tells a coming-of-age story which is clearly his personal story, as he observes the growth of the outside influences which are just beginning to affect his people. The boy is very much a little boy, always acting “in the minute,” reacting to daily events with all the passion of a child, and the author, Galsan Tschinag, is able to communicate the boy’s feelings to a foreign audience in ways which make the Tuvan culture both understandable and unforgettable.