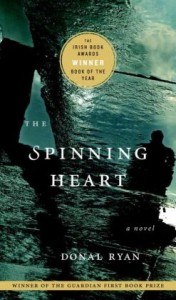

Note: This book was WINNER of the Irish Book Awards “Best Book of the Year” for 2012 and WINNER of the Guardian Award for Best Debut Novel. It was SHORTLISTED for the IMPAC Dublin Award in 2014.

“There’s a red metal heart in the centre of the low front gate, skewered on a rotating hinge. It’s flaking now; the red is nearly gone. It needs to be scraped and sanded and painted and oiled. It still spins in the wind, though. I can hear it creak, creak, creak as I walk away. A flaking, creaking, spinning heart.”—Bobby Mahon, commenting on the heart on his father’s gate.

Though he is one of the best-liked and most admired young men in the small rural village in which he lives, Bobby Mahon hates his father, and the feeling appears to be mutual. Still, he visits him every day at his cottage just beyond the weir – “to see is he dead and every day he lets me down…He stays alive to spite me.” Bobby fears that his father will soon learn that Bobby, like the other employees of Pokey Burke, has been out of work for two months now, having lost everything in the financial troubles that hit Ireland after the economic “bubble” collapsed in 2007. To make things even worse, Pokey has absconded with all the funds that his employees had contributed for their pensions, and Bobby believes that “if [my father] ever finds out how Pokey Burke shafted me, he’ll surely make a full recovery. Pokey could apply to be beatified then having had a miracle ascribed to him.” In the meantime, Bobby dreams of killing his father: “It wouldn’t be murder anyway, just putting the skids under nature. It’s only badness that sustains him.”

Though he is one of the best-liked and most admired young men in the small rural village in which he lives, Bobby Mahon hates his father, and the feeling appears to be mutual. Still, he visits him every day at his cottage just beyond the weir – “to see is he dead and every day he lets me down…He stays alive to spite me.” Bobby fears that his father will soon learn that Bobby, like the other employees of Pokey Burke, has been out of work for two months now, having lost everything in the financial troubles that hit Ireland after the economic “bubble” collapsed in 2007. To make things even worse, Pokey has absconded with all the funds that his employees had contributed for their pensions, and Bobby believes that “if [my father] ever finds out how Pokey Burke shafted me, he’ll surely make a full recovery. Pokey could apply to be beatified then having had a miracle ascribed to him.” In the meantime, Bobby dreams of killing his father: “It wouldn’t be murder anyway, just putting the skids under nature. It’s only badness that sustains him.”

Using Bobby Mahon as the central character around whom most of the action revolves, debut novelist Donal Ryan writes a dramatic and affecting experimental novel in which the story and its symbols, such as the “spinning heart” on his father’s gate, evolve through the points of view of twenty-one different characters, all of them living in the same town, knowing the same people, and contributing to the network of rumors and innuendos as members of “the Teapot Taliban,” as one character calls them. The father of Pokey Burke describes his two sons – Eamonn, his first son, whom he loves more than his second son, Pokey, whom he has spoiled over the years to make up for his lack of affection for him. Pokey’s father, Josie, now blames himself, in part, for the economic problems now affecting so many families in the village.

The village’s young men, in particular, have especially serious problems during the recession, since they often feel that their efforts have been betrayed and their manhood has been compromised. One of them thinks of himself as a loser, and he admires Bobby Mahon because Bobby is one of the few who never made fun of him and who helped him get a job, now lost to the economy. Another tells of his decision to leave for Australia, where he will try to find work. Yet another, a hypochondriac and schizophrenic, lives a life in his imagination and talks about his “reveries.”

Among the women are Lily, who has slept with half the town, but who has somehow managed to put her son through college. Realtin, a woman whose small son Dylan becomes a major character in the action, reveals the effects of the recession on building projects, the one where she lives now housing only two people in the entire estate of forty-four houses. Bridie Connors, a bitter woman who has lost her son in a fishing accident, reveals how evil Bobby’s father has been, at the same time that she also reveals rumors about Bobby’s own unfaithfulness. A daycare owner has hired a male Montessori teacher to work for her, and she has now taken advantage of a program which provides free childcare for a year to parents whose children are of pre-school age. Her business has taken off, though she does not meet the requirements regarding the appropriate teacher-child ratio. Even an observant little girl has a chance to say how her parents have been fighting because her father is out of work and her mother does not get enough hours working at Tesco’s.

The breezy, casual, and sometimes highly confidential stories the characters share with the reader range from darkly humorous to frightening, reflecting the uncertainties of life itself and the often dominating role played by the church and by the characters’ unresolved issues regarding sex. Homosexuality and lesbian relationships are also revealed during the characters’ inner soliloquies. The murder of one person and the kidnapping of another, while initially shocking, develop inexorably from the psychic melange the author has created for a narrative. One character notes that there is also potential for even more violence in the town. “It’s in the air, in the way people are moving around each other with grim faces and shining eyes, either all frantic activity or standing in tight groups, talking quietly and looking at the ground. This must be how things were in the time of the war against the British, when a crowd outside of Mass would suddenly explode into a flying column, guns appearing from under overcoats, killers appearing from inside of ordinary people.”

Eyre Square, with flags representing the fourteen tribes of Galway. One of the characters considers this the best place for girl-watching..

Ultimately, the novel broadens in its scope from a look at the characters in a small village to larger considerations of how we all become who we are, the roles of parents, their goals for us, how they communicate with us, the lessons they teach (sometimes inadvertently), and the role of institutions within the community (church, school, work, and even the pub). Author Donal Ryan’s sense of the telling detail, the revealing comment, and the inner dialogues we have with ourselves creates a memorable novel which shows from “the inside” how the very fabric of a rural community can be affected by unexpected acts of fate.

ALSO by Donal Ryan: THE THING ABOUT DECEMBER

Photos, in order: The author’s photo appears in http://www.tipperarystar.ie/

A red metal heart used as a gate-weight may be found on http://www.pinterest.com

Lough Derg, where the author grew up, is shown on http://en.wikipedia.org Photo by Ludraman.

Eyre Square, where the girl-watching entertained one of the characters, is found here: http://www.imperialhotelgalway.ie/

Killaloe, in the heart of “Brian Boru country,” resembles many other rural communities along the Shannon and Lough Derg. http://discoverkillaloe.ie/

ARC: Archipelago/Steerforth Press