“Yes, I played a part in sending antisocial, feeble-minded girls with deviant sexual tendencies to Sprogo. Yes, they were sterilized. And you would do well to thank me for not having to contend with their offspring running around the streets like rats, for I can assure you the police would be at a loss as to what to do about their feral behavior.”–Carl Wad.

In his fourth novel published in the US and UK, Danish author Jussi Adler-Olsen again tackles an unusual subject, this one based on Denmark’s past history, the imprisonment of sexually active uneducated or mentally challenged women and young girls, some as young as fourteen, on a tiny island in the Great Belt of the Danish Straits. Most of these benighted inmates were poor, and many had been sexually abused at home or had resorted to prostitution as a way of supporting themselves and/or their families. No escape was possible from this island, and bad behavior, sometimes as a result of further sadistic treatment by the matrons and those in power at Sprogo, was punishable by sterilization. Regarded as “forward-thinking” when it was established in 1923, and considered “better” than the institutions in which these women might otherwise have been incarcerated, the Sprogo facility remained open until 1961, a thirty-eight year experiment in creating racial and social “purity” in which fifteen hundred women participated against their wills.

In his fourth novel published in the US and UK, Danish author Jussi Adler-Olsen again tackles an unusual subject, this one based on Denmark’s past history, the imprisonment of sexually active uneducated or mentally challenged women and young girls, some as young as fourteen, on a tiny island in the Great Belt of the Danish Straits. Most of these benighted inmates were poor, and many had been sexually abused at home or had resorted to prostitution as a way of supporting themselves and/or their families. No escape was possible from this island, and bad behavior, sometimes as a result of further sadistic treatment by the matrons and those in power at Sprogo, was punishable by sterilization. Regarded as “forward-thinking” when it was established in 1923, and considered “better” than the institutions in which these women might otherwise have been incarcerated, the Sprogo facility remained open until 1961, a thirty-eight year experiment in creating racial and social “purity” in which fifteen hundred women participated against their wills.

The novel opens in 1985, with Nete Rosen and her wealthy husband of eleven years, Andreas, leaving a reception. On the way out, Nete is accosted by Curt Wad, an older man deeply involved in the Purity Party, then contending for more influence in Danish government. Without warning, Wad insults her, making references to her sordid past, previously unknown to her husband, but well known to Wad, a physician, who knew Nete, then Nete Hermansen, on Sprogo. From this point on, the novel flips back and forth between 1985, and subsequent scenes in 2010, introducing dozens of characters. It is the job of Detective Carl Morck and his staff in Department Q of the Copenhagen Police Department, a group of misfits working in an office hidden in the Department’s basement, to try to solve the old cases, connecting them to the present whenever possible.

Within the first fifty pages, seven different plot lines and the characters associated with them, have opened up, with action occurring over the twenty-five years between 1985 and 2010. The opening scene with Nete Hermansen Rosen, her husband, and Curt Wad is followed immediately by a 2010 case in which the owner of an escort service, the sister of a former police inspector, has acid thrown in her face. Then, suddenly, without preamble, a flashback to 1978 reveals questions about the drowning death of Morck’s uncle, and a blackmailing attempt of Morck by his cousin, in cahoots with someone who wants influence over Morck. A few pages later, a representative of the Purity Party, the ultra-right-wing group which has absorbed some of those who once supported the Sprogo facility, meets at a secret building housing records and aborted fetuses and from which the now elderly Curt Wad is pushing for a major role in Danish government. And this is just the beginning.

Bridge now connecting Sprogo with Nyborg and Norsor on the Great Belt. The distinctively striped lighthouse and the red-roofed women's prison are visible on the left.

In subsequent threads, still within the first fifty pages, Rose, a seriously disturbed but diligent researcher for Morck, has discovered connections between the recent acid attack and similar attacks on other women who, over the past twenty-five years have disappeared without a trace. A journalist becomes the first of many to investigate the Purity Party and runs afoul of its members, who will stop at nothing. Questions arise about an unsolved shooting a couple of years ago in which Morck was shot with a nail gun, one of his partners killed, and a third left paralyzed. All these subplots are capped off when Nete Hermansen begins to plan her revenge against six different people, most of whom the reader has not yet heard of. As each of these threads develops further, the reader is challenged to keep all the time periods, all the characters and all the action straight, at the same time that s/he is also trying to see if there are any connections among all these subplots.

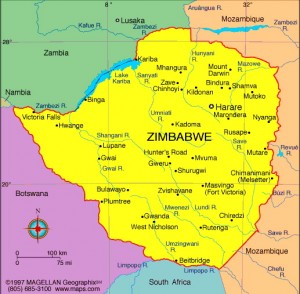

Double-click, then scroll down to enlarge map. Sprogo is slightly NW of the “elbow” in red line through the Great Belt, and is part of a bridge/tunnel connection between the two much bigger islands of Funen (Fyn) to the west and Zealand to the east.

For those familiar with the earlier novels in the series, this novel may be a surprise. Adler-Olsen’s first novel, The Keeper of Lost Causes, introduced lively, vibrant characterizations of Carl Morck and the mysterious and (ironically named) Hafez el-Assad from Syria, whom I described in my review of The Keeper of Lost Causes as “the best side-kick I have come across in years.” Filled with some great humor, heart-pounding excitement, and genuine warmth and emotion which involves the reader, that novel was, in my opinion, “as close to perfect as a mystery can get.” The second novel, The Absent One, concerned itself far less with character than did the first novel, though it introduces Rose, a secretary on “mile-high heels” who has been cheering up the other secretaries with her “infectious humour” and who becomes Morck’s irrepressible assistant. Rose is further developed (and Morck and Assad seem to have even less new development) in the third novel, A Conspiracy of Faith, where her serious psychological problems become an issue, though that idea goes no further in this new novel.

In the The Purity of Vengeance, Adler-Olsen has depended heavily on the characterizations from his earlier novels, adding little to what we already know about Morck, Assad, and Rose, but making quantum leaps in the number of subplots and their complications. The number of complications is so large here that the novel becomes an intellectual exercise, with fewer intense action scenes that involve the reader, and much less feeling and humor (except gross bathroom humor, of which there is plenty). The tight plot of Keeper of Lost Causes allowed the author to explore characters and involve the reader, but that is not possible in this dense and plot-heavy novel. As Nete  ages into her sixties during this novel, she evokes pity for the horrors of her life, but we know too little about her transformation – from illiterate, young Sprogo victim to beloved wife of wealthy Andreas Rosen, and then to sociopathic avenger – to identify and sympathize with her. The implausibilities in some of the plot lines culminate in the conclusion, about which the less said, the better. As a fan of Adler-Olsen, I was both surprised and disappointed by the changes that have emerged with this novel, and I am hoping that more careful editing by the author himself as he plans his future novels will bring back the quick paced fun and humor, the characterizations, and the tight, dramatic, and action-packed plotting I celebrated in my review of The Keeper of Lost Causes.

ages into her sixties during this novel, she evokes pity for the horrors of her life, but we know too little about her transformation – from illiterate, young Sprogo victim to beloved wife of wealthy Andreas Rosen, and then to sociopathic avenger – to identify and sympathize with her. The implausibilities in some of the plot lines culminate in the conclusion, about which the less said, the better. As a fan of Adler-Olsen, I was both surprised and disappointed by the changes that have emerged with this novel, and I am hoping that more careful editing by the author himself as he plans his future novels will bring back the quick paced fun and humor, the characterizations, and the tight, dramatic, and action-packed plotting I celebrated in my review of The Keeper of Lost Causes.

ALSO by Adler-Olsen: THE KEEPER OF LOST CAUSES, THE ABSENT ONE, THE CONSPIRACY OF FAITH, THE MARCO EFFECT

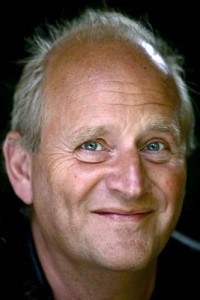

Photos, in order: The author’s photo by Jens Norgaard Larsen appears on http://www.bt.dk/

The Women’s Prison at Sprogo is from http://www.kulturarv.dk/

The bridge connecting Sprogo to Lyborg and Korsor is photographed by Jeppe Madsen on http://www.trekearth.com/

On this map of the Danish Straits, Sprogo is slightly NW of the “elbow” in red line through the Great Belt, and is part of a bridge/tunnel connection between the two much bigger islands of Funen (Fyn) to the west and Zealand (where Copenhagen is located) to the east. Just click on the map to enlarge, then scroll down. On the NASA photo, it is possible to see the bridge that connects Sprogo to the two larger islands. http://www.eoearth.org/

ARC: Dutton

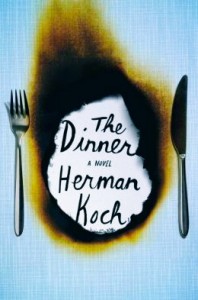

This book by Dutch author Herman Koch has been sitting in my bookcase for almost a year. Occasionally, I have taken it out, when I have read enthusiastic reviews from people whose opinions I respect, but none of the reviews have said much about the action that occurs in this book, and I have always put it away, unread, thinking that the book was probably something like My Dinner with Andre. This week when I picked it up yet again, I opened it and began reading. Seventy-five pages later, I was fully engaged, reading with interest and some excitement, and thoroughly humiliated by my own willingness to jump to conclusions about a book that I had not given a fair chance. And the more I read, the more I understood why none of the reviewers whose reviews I have checked have much to say about the book’s plot: they can’t say anything without spoiling the story.

This book by Dutch author Herman Koch has been sitting in my bookcase for almost a year. Occasionally, I have taken it out, when I have read enthusiastic reviews from people whose opinions I respect, but none of the reviews have said much about the action that occurs in this book, and I have always put it away, unread, thinking that the book was probably something like My Dinner with Andre. This week when I picked it up yet again, I opened it and began reading. Seventy-five pages later, I was fully engaged, reading with interest and some excitement, and thoroughly humiliated by my own willingness to jump to conclusions about a book that I had not given a fair chance. And the more I read, the more I understood why none of the reviewers whose reviews I have checked have much to say about the book’s plot: they can’t say anything without spoiling the story.

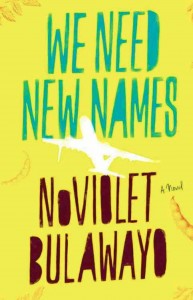

In this remarkable “novel” which defies genre – feeling like a memoir and structured like a collection of short stories – author NoViolet Bulawayo, from Zimbabwe, revisits her former country and its on-going, horrific history. Main character, Darling, is only ten; her friends Sbho, Godknows, Bastard, Chipo, and Stina, who has no birth certificate, are all close to her in age. Though they once attended school, their teachers “have left to teach over in South Africa and Botswana and Namibia and them, where there’s better money.” They amuse themselves by playing “the country-country game” and “Find bin-Laden.” They take hikes to Budapest, a wealthier neighboring community, to steal mangoes, and they sometimes accompany their mothers and grandparents to evangelical meetings under the mopane tree, and later up “the mountain.” Their lives are all turned upside down when government-tolerated bullies bulldoze all their houses. Now they live in a shantytown ironically named Paradise, made from cardboard, tin, and plastic, where their biggest excitement is the arrival of NGO trucks with the food which keeps them from starving.

In this remarkable “novel” which defies genre – feeling like a memoir and structured like a collection of short stories – author NoViolet Bulawayo, from Zimbabwe, revisits her former country and its on-going, horrific history. Main character, Darling, is only ten; her friends Sbho, Godknows, Bastard, Chipo, and Stina, who has no birth certificate, are all close to her in age. Though they once attended school, their teachers “have left to teach over in South Africa and Botswana and Namibia and them, where there’s better money.” They amuse themselves by playing “the country-country game” and “Find bin-Laden.” They take hikes to Budapest, a wealthier neighboring community, to steal mangoes, and they sometimes accompany their mothers and grandparents to evangelical meetings under the mopane tree, and later up “the mountain.” Their lives are all turned upside down when government-tolerated bullies bulldoze all their houses. Now they live in a shantytown ironically named Paradise, made from cardboard, tin, and plastic, where their biggest excitement is the arrival of NGO trucks with the food which keeps them from starving.

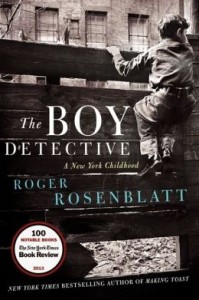

In his memoir of his childhood in the Gramercy Park neighborhood of New York City (18th – 22nd Streets between Park Ave. South and 3rd Ave.), award-winning journalist/essayist Roger Rosenblatt uses the conceit of man’s having separate souls – one for the senses and one for the intellect – as the basis of a memoir about growing up in New York City during the 1950s and afterward. Rosenblatt, now seventy-two, is teaching a course in memoir writing at Stony Brook’s Manhattan campus in February, 2011, when he begins his own memoir. He begins walking the streets he walked as a boy, remembering what businesses used to occupy the premises of various buildings, remembering the people he knew who lived there, and tying his own life as a resident of that specific neighborhood to the many writers and actors who also shared the same neighborhood at different times in history. Delightful, filled with insights into how a “real” writer thinks as he lives his childhood, and thoughtful about how our early lives affect not only our (learned) ways of thinking but also our ways of acting, this memoir is a must for those who love writing, think they might want to become writers, or just want a wonderful, complete reading experience created by a writer who started as a devout reader.

In his memoir of his childhood in the Gramercy Park neighborhood of New York City (18th – 22nd Streets between Park Ave. South and 3rd Ave.), award-winning journalist/essayist Roger Rosenblatt uses the conceit of man’s having separate souls – one for the senses and one for the intellect – as the basis of a memoir about growing up in New York City during the 1950s and afterward. Rosenblatt, now seventy-two, is teaching a course in memoir writing at Stony Brook’s Manhattan campus in February, 2011, when he begins his own memoir. He begins walking the streets he walked as a boy, remembering what businesses used to occupy the premises of various buildings, remembering the people he knew who lived there, and tying his own life as a resident of that specific neighborhood to the many writers and actors who also shared the same neighborhood at different times in history. Delightful, filled with insights into how a “real” writer thinks as he lives his childhood, and thoughtful about how our early lives affect not only our (learned) ways of thinking but also our ways of acting, this memoir is a must for those who love writing, think they might want to become writers, or just want a wonderful, complete reading experience created by a writer who started as a devout reader.

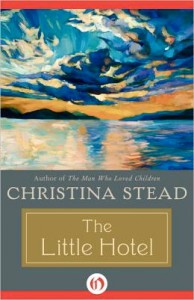

Winner of the prestigious Patrick White Award in her native Australia in 1979, Christina Stead (1902 – 1983), acclaimed in England and Australia, still remains unknown to most readers in the United States, and that’s a pity. Her 1973 novel The Little Hotel, given to me by a friend from England, reveals her deliciously twisted sense of humor, her pointed social satire, and her vividly depicted but often very sad characters, and I am now poring through Amazon’s Marketplace listings to find as many of her other sadly neglected novels as I can. In this novel, set in a small hotel on Lake Geneva in the immediate aftermath of World War II, Stead introduces an assortment of bizarre characters who live at the small Hotel Swiss-Touring for various lengths of time, some of them for a season, and a few as residents. Most of them are there because they cannot afford the more elegant accommodations to which they have been accustomed, though the twenty-six-year-old hotelkeeper, Selda Bonnard, and her slightly older husband Roger do their best to meet their guests’ needs. Touring artists associated with a local nightclub, and the road companies that play the casino, also occupy the hotel, residing on another floor above the guests.

Winner of the prestigious Patrick White Award in her native Australia in 1979, Christina Stead (1902 – 1983), acclaimed in England and Australia, still remains unknown to most readers in the United States, and that’s a pity. Her 1973 novel The Little Hotel, given to me by a friend from England, reveals her deliciously twisted sense of humor, her pointed social satire, and her vividly depicted but often very sad characters, and I am now poring through Amazon’s Marketplace listings to find as many of her other sadly neglected novels as I can. In this novel, set in a small hotel on Lake Geneva in the immediate aftermath of World War II, Stead introduces an assortment of bizarre characters who live at the small Hotel Swiss-Touring for various lengths of time, some of them for a season, and a few as residents. Most of them are there because they cannot afford the more elegant accommodations to which they have been accustomed, though the twenty-six-year-old hotelkeeper, Selda Bonnard, and her slightly older husband Roger do their best to meet their guests’ needs. Touring artists associated with a local nightclub, and the road companies that play the casino, also occupy the hotel, residing on another floor above the guests.