As close to perfect as a mystery can get, award-winning Danish author Jussi Adler-Olsen’s first novel to be translated into English has something that will entertain everyone. Very exciting with its unusual plot, and filled with characters with whom the reader will identify, the novel is complex but not so dependent on odd details that the reader gets lost in complications. It is also genuinely heart breaking in places without being sentimental; warm; and often very funny, to top it off. As much fun as the novel is to read, Adler-Olsen also has something to say about contemporary life, creating an underlying thematic structure which carries a powerful kick as the novel comes to its conclusion. Who could want more than that?

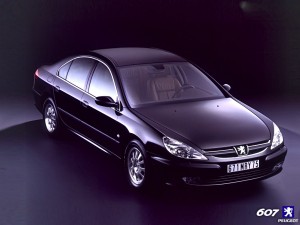

Copenhagen Homicide Detective Carl Morck has been on leave for several weeks after being shot, and he is an emotional mess. One of his partners was killed in the same incident, and the other, a six foot, nine-inch giant, now lies hospitalized, paralyzed from the neck down. Described even on a good day as “lazy, surly, morose, always bitching, and [constantly] treating his colleagues like crap,” Morck, upon his reluctant return to work, has not been welcomed back by anyone: life has gone on for the department, and the other officers have been busy solving new cases. When a woman in Parliament succeeds in creating a new police investigative unit, called Department Q, to work on “cases deserving special scrutiny,” especially unsolved cases, however, the Chief of Homicide sees this as as the perfect chance to get Morck out of the way–having him run the one-man department from the basement of the station, while he himself uses the funding that was appropriated for Department Q for other projects and other cases. Morck is happy to continue his bad habits in the basement, sitting with his feet up, sleeping, and smoking. As a new department head whose job has been well funded, however, Morck demands and gets a new car, better than standard issue, and an assistant, who turns out to be very different from “standard issue.”

appropriated for Department Q for other projects and other cases. Morck is happy to continue his bad habits in the basement, sitting with his feet up, sleeping, and smoking. As a new department head whose job has been well funded, however, Morck demands and gets a new car, better than standard issue, and an assistant, who turns out to be very different from “standard issue.”

His assistant, whom Morck regards as someone who will be primarily responsible for doing the custodial work in the basement while he himself snoozes or watches TV, is the ingenuous and charming (and ironically named), Hafez el-Assad, a mystery man from a Middle Eastern country, who quickly becomes fascinated by cases which he cannot help but begin to investigate on his own. As time goes on, and Assad magically pries out information from the grumpiest of the secretaries “upstairs,” he often provides remarkable new insights into cold cases, eventually reawakening the almost dead professional curiosity of Carl Morck. Front and center is the five-year-old case of Merete Lynggaard, vice-chairperson of the Social Democratic party in the Danish Parliament. Merete, accompanying her mute and handicapped brother on a ferry from Rodby to Puttgarden, vanished aboard the boat after they had a disagreement. After nearly five years, no trace of her has ever been found, and her brother, institutionalized, remains mute.

Carl Morck's "better than standard issue" car, the Peugeot 607

Alternating with Morck’s point of view is that of a woman who, we quickly discover, is Merete Lynggaard, imprisoned in a pressurized room by someone she has never seen, subjected to periods of darkness, alternating with periods of bright light, with the air pressure slowly increasing over the length of her imprisonment. If anyone tries to break in to free her, her body will virtually explode from the change of pressure. As Assad keeps using his mysterious talents to ferret out information to help Morck, the case becomes more complicated, and since Morck is still dealing with post-traumatic stress and guilt from the shooting which he alone survived (almost) intact, the reader looks forward to the scenes in which Assad, ingenuously and often humorously, keeps asking questions of Morck, telling him new things he has discovered, and adding a light touch to the otherwise a grim and grisly plot.

The Schleswig-Holstein ferry, on which Merete Lynggaard disappears

Assad’s role as a person who has both heroic qualities and a naïve warmth also makes the ending even more dramatic, serving as a contrast to the personal misery which affects virtually all the other characters, misery which is imposed on them unexpectedly, not by fate, but by other people. Accidents and, essentially, the rolls of the dice mean the difference between escape from disaster and death, permanent disabilities, psychological traumas, and unexpected changes in their lives and their outlook on life. There are, however, enough questions about Assad’s background to lead the reader to question his own history. His name, his reasons for asylum in Denmark, his immigration status, and his apparent familiarity with crimes and punishments make him a wonderfully mysterious character whose own story will undoubtedly become a feature in the remaining three (so far) novels in this series, not yet translated into English. He is the most intriguing side-kick I have come across in years, and he obviously has his own story to tell.

Decompression chamber

As the author examines the various aspects of power which affect people from all walks of life, he raises questions about government, about policing, and about man’s expectations—and whether man should, in fact, have any expectations at all. When faced with pressures from those whose power is vastly superior to one’s own, how far can someone go to protect his own integrity before caving in to power? What does it take to maintain a sense of personal integrity in a lifetime in which people are subjected to all sorts of outside pressures which have personal implications. Is that even relevant? And on its highest level, do those in positions of power have ethical and moral obligations toward those they oversee? Though the answers seems obvious, issues of everyday survival make absolute conclusions less assured. For a policeman, it maybe even more difficult. As the police chief says to Morck, “How many times can a person handle that sort of [life-or-death] situation, and when does he decide he just can’t take it any more?…We’ve all been up shit creek at one time or another. Anyone who hasn’t is not a real cop. We just have to go out there, knowing that we might be out of our depth once in a while. That’s our job.”

Also by Jussi Adler-Olsen: THE ABSENT ONE , A CONSPIRACY OF FAITH, THE PURITY OF VENGEANCE, THE MARCO EFFECT

Photos, in order: The photo of the author and a great interview are from http://www.newstatesman.com

The “better than standard issue” car that Carl Morck demands and gets is the Peugeot 607, shown here: http://peugeot.mainspot.net

Merete Lynggaard disappears while on the Schleswig-Holstein ferry from Rodby to Puttgarden: http://www.scandlines.com

A portable hyperbaric chamber, used to help divers cope with dramatic changes in atmospheric pressure, an issue in this novel, is seen on http://www.oobject.com

ARC: Dutton