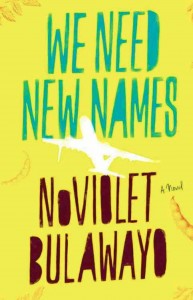

Note: This novel was SHORTLISTED for the Man Booker Prize for 2013.

“The men driving the bulldozers are laughing. I hear the adults saying, Why why why, what have we done, what have we done, what have we done? Then the lorries come carrying the police with those guns and baton sticks and we run and hide inside the houses, but it’s no use hiding because the bulldozers start bulldozing and bulldozing and we are screaming and screaming.”

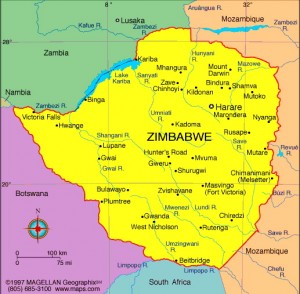

In this remarkable “novel” which defies genre – feeling like a memoir and structured like a collection of short stories – author NoViolet Bulawayo, from Zimbabwe, revisits her former country and its on-going, horrific history. Main character, Darling, is only ten; her friends Sbho, Godknows, Bastard, Chipo, and Stina, who has no birth certificate, are all close to her in age. Though they once attended school, their teachers “have left to teach over in South Africa and Botswana and Namibia and them, where there’s better money.” They amuse themselves by playing “the country-country game” and “Find bin-Laden.” They take hikes to Budapest, a wealthier neighboring community, to steal mangoes, and they sometimes accompany their mothers and grandparents to evangelical meetings under the mopane tree, and later up “the mountain.” Their lives are all turned upside down when government-tolerated bullies bulldoze all their houses. Now they live in a shantytown ironically named Paradise, made from cardboard, tin, and plastic, where their biggest excitement is the arrival of NGO trucks with the food which keeps them from starving.

In this remarkable “novel” which defies genre – feeling like a memoir and structured like a collection of short stories – author NoViolet Bulawayo, from Zimbabwe, revisits her former country and its on-going, horrific history. Main character, Darling, is only ten; her friends Sbho, Godknows, Bastard, Chipo, and Stina, who has no birth certificate, are all close to her in age. Though they once attended school, their teachers “have left to teach over in South Africa and Botswana and Namibia and them, where there’s better money.” They amuse themselves by playing “the country-country game” and “Find bin-Laden.” They take hikes to Budapest, a wealthier neighboring community, to steal mangoes, and they sometimes accompany their mothers and grandparents to evangelical meetings under the mopane tree, and later up “the mountain.” Their lives are all turned upside down when government-tolerated bullies bulldoze all their houses. Now they live in a shantytown ironically named Paradise, made from cardboard, tin, and plastic, where their biggest excitement is the arrival of NGO trucks with the food which keeps them from starving.

The author never mentions the name of President Robert Mugabe, a former revolutionary who, with his supporters, successfully fought for independence from the white minority government of Ian Smith in what was then known as Rhodesia, a British colony. Chosen President of the re-named independent country of Zimbabwe in 1980, he has continued to win Zimbabwe’s disputed elections for the past thirty-four years, despite international sanctions imposed by the West. Though much of the country’s land was developed and planted by British farmers, some of whom were born there and who lived there for three or four generations, Mugabe instituted a program to “redistribute” their land to his own supporters. This “redistribution” led to the takeover of virtually all white-owned land and a rule by government-tolerated thugs, some of them under no control at all, as the families of Darling and her friends discovered when their own houses were destroyed and their own land seized by fellow citizens who simply decided to take it.

The scenes depicting Darling’s life, as she innocently tells her story, are shocking, not only for the facts which are depicted so graphically, but also for the sense she reveals that these experiences are somehow “normal” and even “ordinary.” The action, which begins in the late 1980s, shows that nothing is sacred now, and no rules, except the traditions of the old folks, seem to have survived the horrors of “independence,” which might have been a glorious celebration. Her story becomes especially vivid because she and her friends behave like children the world over, playing games, fighting with each other, searching for excitement, and creating games using sticks and found materials. Unfortunately, she and her young friends are also naïve about the facts of life, and the pregnancy of one of Darling’s eleven-year-old friends, is a complete mystery and regarded as a problem to be solved by the children themselves. Even when they decide they will get rid of the friend’s belly (because it makes it “hard to play”), they think of its removal as a game in which they will imitate a program that Darling once saw on TV in Harare: ER. They take new names for the activity: Dr. Bullet, Dr. Roz, and Dr. Cutter.

“When things fall apart, the children of the land scurry and scatter like birds escaping a burning sky,” the author notes, and Darling is no exception. Her Aunt Fostalina lives in “destroyedmichygen,” in the US, and Darling hopes that she may one day go to live with her. The novel divides into two parts at the midpoint, and the second half does, in fact, take place, first, in “destroyedmichygen” and later in Kalamazoo, 150 miles away, following Darling through school in the US and eventually many years of work. This allows the novel to broaden into a wider story of the immigrant experience and the agonies of displacement, in this case told by a child who misses her friends, her home, and her mother, a child who daily experiences bullying, the materialistic culture of her Aunt and Uncle Kojo, and the many cultural difficulties of speaking a different language and having a totally different background, one so different that she could never have prepared herself for the change.

As her updated story unfolds in the US, Darling and two new friends, one an immigrant like herself, have far too much free time, primarily because their families are away much of time working to send money back to their home countries. Some new characters, one of them an elderly man from Zimbabwe who has become mentally unbalanced by the shock of leaving home, add further insights into the difficulties of changing cultures, especially since they are all in the US under expired visas. They cannot return home for a visit because they would have no valid visa to re-enter. Though they always promise their families in phone calls that they will visit, most of these new immigrants know that they will probably never see them again, their deception adding to their difficulties in adjusting to their new world, an agony assuaged only by sending what money they can afford to keep them all alive.

American urban culture comes in for some comment here, too, based on what appears to have been the author’s own observations. In one of the novel’s few humorous episodes, one of Darling’s friends insists on speaking “Ebonics,” instead of standard English, requiring Darling to learn yet another dialect (now discredited, academically) as she adjusts to life in an English-speaking world. Violence in the cities and the ongoing agony of immigrants who came here because it was truly their last chance at life itself – people willing to work hard but unable to get jobs because they are undocumented – add to the drama of this hard-hitting and powerful novel which shows in new, immediate ways the need to think globally.

Note: When Darling and her friends see thugs destroying the large house of a white family, they watch in horror – but understand how it feels. In this PBS documentary, a family responds to the threats to their farm (“Mugabe and the White African”)

Photos, in order: The author’s photo is from http://www.theguardian.com

The church meeting under the mopane tree is found on http://www.adventistmission.org/

The Robert Mugabe photo, by Alexander Joe, appears on http://www.theguardian.com

The traditional assegai, a weapon made by hand here by Heather Harvey, is from http://www.heavinforge.co.za

The map of Zimbabwe is from http://www.infoplease.com. Click on the map to enlarge it.