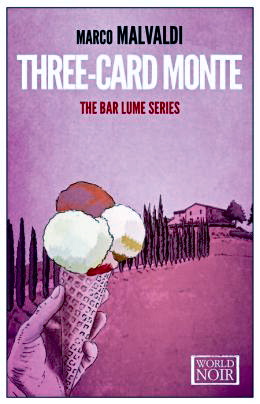

Note: Author Marco Malvaldi is a WINNER of the Castiglioncello Prize for Fiction for his crime novels.

“A boring job can bring out the best in a person…Go onto automatic pilot, and let your brain keep ticking over. When he developed the theory of relativity, Einstein was working in a patent office. Boll was a census gatherer, and Bulgakov a country doctor…Borges was a librarian… Give an imaginative man a dull, repetitive job that puts him in contact with others…and there’s a strong possibility you’ll produce a Nobel Prize winner.”—Massimo Viviani, owner-bartender of the Bar Lume.

The second novel in the Bar Lume series, by Marco Malvaldi, Three-Card Monte brings us once more into the life of Pineta, a small town in Tuscany, near Pisa, with the Bar Lume and its often hilarious characters as its focal point. Owned by thirty-seven-year-old Massimo Viviani, a single man trying to put his life back together after a devastating romantic breakup, the Bar Lume has become a refuge for him – or as much of a refuge as any place can be when it is occupied every day by four cranky and gossipy oldtimers who regard “their table” at the Bar Lume as their “office.” Ranging in age from seventy-three to eighty-two, they have known each other all their lives –and they keep up a running commentary on everything that is happening in town and everyone who is involved in it. Drop one word in front of this elderly quartet from the Bar Lume, and it will make its way instantly all over town without any of the men ever having to leave the “office.”

The second novel in the Bar Lume series, by Marco Malvaldi, Three-Card Monte brings us once more into the life of Pineta, a small town in Tuscany, near Pisa, with the Bar Lume and its often hilarious characters as its focal point. Owned by thirty-seven-year-old Massimo Viviani, a single man trying to put his life back together after a devastating romantic breakup, the Bar Lume has become a refuge for him – or as much of a refuge as any place can be when it is occupied every day by four cranky and gossipy oldtimers who regard “their table” at the Bar Lume as their “office.” Ranging in age from seventy-three to eighty-two, they have known each other all their lives –and they keep up a running commentary on everything that is happening in town and everyone who is involved in it. Drop one word in front of this elderly quartet from the Bar Lume, and it will make its way instantly all over town without any of the men ever having to leave the “office.”

Massimo’s grandfather Ampelio, the oldest of the four patrons, has been “the uncontested winner of [a] cursing competition at a local festival,” and he is the best story-teller among the group. Once he decides to tell a story, “the only thing that could stop him…would be military intervention by NATO.” He is joined at the table by Aldo, the owner of an upscale restaurant and catering service. Pilade del Tacca, formerly employed at the town hall, knows everyone, despite the fact that he is difficult and as “unpleasant as a piece of [something] under your shoe.” Gino, a retired postal worker, looks “halfway between a nursing home patient and an escaped convict,” with “vaguely nostalgic ideas about the Fascist period.” Together they are a formidable cast of characters – independent, earthy, garrulous, and hilariously funny – who keep the patient bartender Massimo entertained, sometimes frustrated, and constantly busy as they tease each other while also revealing their values and their attitudes toward life.

The Ponte Solferino in Pisa, which Massimo crosses on his way to the university to ask for technical help in solving the mystery here.

In the previous novel in the series, Game for Five, in which a local murder takes place and is investigated on the local level, Massimo the bartender is seen as a sympathetic character who astutely “directs traffic” within that novel, helping the sometimes incompetent police as the novel leads up to the climax, in which Massimo solves the murder. We know only as much about him as we need to know to make us empathize with him.

Three-Card Monte, however, is quite different from this in its focus, significantly expanding Massimo’s character and showing him to be a far more complex character capable of solving a far more complicated murder than in the previous novel. The opening quotation from this review alone is ample proof that Massimo is starting to find his intellectual “mojo” again as he gets back on his feet emotionally.

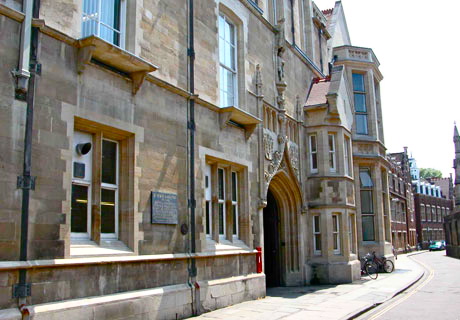

Scientists at the University of Pisa use their technical expertise to help investigate the death of Asahara.

As the novel opens, Koichi Kawaguchi, a computer expert, has just arrived at the airport on his way to the Twelfth International Workshop in Macromolecular and Biomacromolecular Chemistry in Pineta, one of about two hundred theoretical and experimental scientists who are attending. Author Malvaldi obviously has fun with this introduction, commenting on the reactions of Kawaguchi to Italy’s “airport chaos,” which he finds far more orderly than the chaos at Narita – and to such amenities as the men’s rooms, far different from those in Japan. Cultural differences among the various delegates are also noted as the novel develops. When, for example, the sloppily dressed Prof. A. C. J. Snijders, from the Netherlands, decides not to attend a conference session in which he has no interest, he simply does not go, spending the afternoon swimming and reading a book at the hotel pool instead. Kawaguchi has no interest in the lectures – they are not even in his specialty – yet he has to be there, looking sharp, for business reasons, and he suffers terribly as he watches Snijders having fun at the pool. Kawaguchi’s life takes a new turn when the main speaker, elderly Kiminobu Asahara, is found dead in his hotel room.

Massimo is furious when he discovers a scooter blocking “his” parking spot at an arch near his apartment.

Inspector Vinicio Fusco, of the local police, is in charge of the investigation, and as he does not speak either Japanese or English, he calls on Massimo, who speaks English, to translate his Italian into English and convey his questions to the English-speaking Kawaguchi, who has been chosen to be a translator, as they interview Japanese participants who knew Asahara. Koichi asks Fusco’s questions to the Japanese participants, conveys their (edited) answers in English to Massimo (whom he thinks has “a face like a Taliban,”), who then edits again and translates most of what he hears to Fusco in Italian. As the investigation develops, it becomes, in some ways like “three-card monte,” a game of trickery which Aldo learned when he worked on board a ship.

At a bookstore near his apartment, Massimo buys a book, then gets an idea when he sees this one on the counter. He buys it as “an homage to the author,” then returns to the arch and disables the scooter blocking his parking spot.

The solution to the mystery, which comes at the very end, becomes almost incidental to all the fun of the novel and the amusing commentary the author makes on life in Italy, including the politics of academia, the behavior of the press, and the inability of anyone in the whole country to keep a secret. The novel is great fun to read, despite the fact that the conclusion, as it turns out, depends on more technical knowledge than I possess. It is here in the conclusion that the author’s own background as a scientist (with a Master’s degree in Chemistry) is revealed, and though he reduces the complications to the bare minimum, my own science background, limited as it is, occurred too far in the past to be relevant here. Short, hilarious, and clever, with increasingly complex characters, Three-Card Monte is a delightful light entertainment, perfect for summer reading.

ALSO by Malvaldi: GAME FOR FIVE

NOTE: The trickery of the card game of Three-Card Monte, is shown and explained in this video:

Photos, in order: The author’s photo is found here: http://lettura.corriere.it/

The Ponte Solferino in Pisa appears on http://www.progettosnaps.net/

A few of the buildings at the University of Pisa are shown on http://en.wikipedia.org/

THREE METERS ABOVE THE SKY by Federico Moccia is sitting on the counter when Massimo goes to buy a book, giving him an idea on how to solve the scooter problem. He buys the book as “an homage to the author.”

ARC: Europa Editions

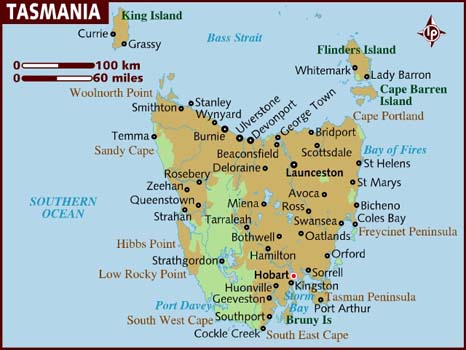

Dark, stark, and potent in its story and its message, Past the Shallows reduces life to its most basic elements as perceived by two young brothers, Miles and Harry Curren, who share the story of their uncertain lives on an island at the tail end of the inhabited world. Tasmania, off the south coast of Australia, where their father fishes for abalone in the dark water, offers no refuge, either physically or emotionally, from fate and the elements – just open water from there all the way to Antarctica. As difficult as the setting may be, the boys’ dysfunctional family is worse. The boys’ father, a threatening and often intemperate “hard man,” offers the young boys no emotional support in their difficult lives made worse by his drinking and irrational behavior. Their older brother Joe is living alone at his grandfather’s house, clearing it out after his death. Their mother died so long ago that they remember almost nothing of her or the car crash which killed her, just occasional flashes of memory of the ride they shared with her up to the fatal moment. The only woman with whom they have any contact is their Aunty Jean, whose own attitudes toward them alternate between callous indifference and the kind of attention that usually arises more from obligation than from love. There is no softness, no warmth of love, from anyone in their lives.

Dark, stark, and potent in its story and its message, Past the Shallows reduces life to its most basic elements as perceived by two young brothers, Miles and Harry Curren, who share the story of their uncertain lives on an island at the tail end of the inhabited world. Tasmania, off the south coast of Australia, where their father fishes for abalone in the dark water, offers no refuge, either physically or emotionally, from fate and the elements – just open water from there all the way to Antarctica. As difficult as the setting may be, the boys’ dysfunctional family is worse. The boys’ father, a threatening and often intemperate “hard man,” offers the young boys no emotional support in their difficult lives made worse by his drinking and irrational behavior. Their older brother Joe is living alone at his grandfather’s house, clearing it out after his death. Their mother died so long ago that they remember almost nothing of her or the car crash which killed her, just occasional flashes of memory of the ride they shared with her up to the fatal moment. The only woman with whom they have any contact is their Aunty Jean, whose own attitudes toward them alternate between callous indifference and the kind of attention that usually arises more from obligation than from love. There is no softness, no warmth of love, from anyone in their lives.

So wild and imaginative that it challenges the very meaning of the word “farce,” which, for me is usually something light-weight, silly, and easily forgotten, Swedish author Jonas Jonasson expands this “farce” beyond the customary local or domestic focus and uses the whole world as his stage. Drawing his characters from South Africa, Israel, China, and Sweden, with a couple of Americans also earning passing swipes, he focuses on cultural and racial issues; world affairs, including the modern political history of several countries; and the accidents of history which have the power to change the world. The craziness starts with the novel’s over-the-top opening line: “In some ways they were lucky, the latrine emptiers in South Africa’s largest shantytown. After all, they had both a job and a roof over their heads.” And for the next four hundred pages, the bold absurdity continues, spreading outward until it eventually absorbs the kings, presidents, and prime ministers of Europe, the Middle East, and Asia.

So wild and imaginative that it challenges the very meaning of the word “farce,” which, for me is usually something light-weight, silly, and easily forgotten, Swedish author Jonas Jonasson expands this “farce” beyond the customary local or domestic focus and uses the whole world as his stage. Drawing his characters from South Africa, Israel, China, and Sweden, with a couple of Americans also earning passing swipes, he focuses on cultural and racial issues; world affairs, including the modern political history of several countries; and the accidents of history which have the power to change the world. The craziness starts with the novel’s over-the-top opening line: “In some ways they were lucky, the latrine emptiers in South Africa’s largest shantytown. After all, they had both a job and a roof over their heads.” And for the next four hundred pages, the bold absurdity continues, spreading outward until it eventually absorbs the kings, presidents, and prime ministers of Europe, the Middle East, and Asia.

re the most popular book reviews on this site from January 1, 2014 – June 31, 2014:

re the most popular book reviews on this site from January 1, 2014 – June 31, 2014:

8.

8.  British author Jennie Rooney, who studied history at Cambridge, was first inspired to write this story of spies within Britain’s top secret atomic research labs when she read a newspaper article in 1999 about Melita Norwood, age eighty-seven, who was revealed to have been the “most important and longest-serving Soviet spy of the Cold War era.” After her unmasking, Ms. Norwood’s interview with the press and her appearance on television, in which she was “rather economical with the truth, and not hugely remorseful,” according to Rooney, energized Rooney to investigate further. At the same time she began to imagine the circumstances under which a seemingly innocuous worker for several British labs doing atomic research could have willingly passed documents and research notes to Russia for use in their own frantic race to develop nuclear weapons – all this without coming to the attention of MI5, the British Security Service until fifty years later. Just as importantly, Rooney also wanted to understand why and how Norwood – or anyone else, for that matter – could betray her own country and be able to live with herself, quietly and comfortably, in the very country whose secrets she had so treacherously revealed.

British author Jennie Rooney, who studied history at Cambridge, was first inspired to write this story of spies within Britain’s top secret atomic research labs when she read a newspaper article in 1999 about Melita Norwood, age eighty-seven, who was revealed to have been the “most important and longest-serving Soviet spy of the Cold War era.” After her unmasking, Ms. Norwood’s interview with the press and her appearance on television, in which she was “rather economical with the truth, and not hugely remorseful,” according to Rooney, energized Rooney to investigate further. At the same time she began to imagine the circumstances under which a seemingly innocuous worker for several British labs doing atomic research could have willingly passed documents and research notes to Russia for use in their own frantic race to develop nuclear weapons – all this without coming to the attention of MI5, the British Security Service until fifty years later. Just as importantly, Rooney also wanted to understand why and how Norwood – or anyone else, for that matter – could betray her own country and be able to live with herself, quietly and comfortably, in the very country whose secrets she had so treacherously revealed.