“I saw myself how my wit exceeded that of other men…”

Those who grew up on the poetic translations of the Odyssey by Robert Fitzgerald and Richmond Lattimore will be surprised, to say the least, at this new version of the “lost books” of the Odyssey by Zachary Mason. Both of those earlier translator/poets treat this epic as the monument of Greek culture that it is – a long poem from three thousand years ago intended to be sung by traveling bards as a way of preserving their culture and religion. In the opening of Fitzgerald’s memorable translation, for example, the bard calls on the Muse for help, praying:

“Sing in me, Muse, and through me tell the story

of that man skilled in all ways of contending,

the wanderer, harried for years on end,

after he plundered the stronghold

on the proud height of Troy.

He saw the townlands

and learned the minds of many distant men,

and weathered many bitter nights and days

in his deep heart at sea…”

Mason’s newly published version of this story, by contrast, takes a post-modernist approach – casual, playful, earthy, and even scatological. At one point in Mason’s version of The Lost Books of the Odyssey, Odysseus muses about the fact that “I was ideally suited to be a bard, a profession fit only for villeins, wandering masterless men who live at the pleasure of their landed betters, as my father reminded me when I broached the idea. He and his men would say things like, ‘We are here to live the stories, not compose them!’”

Mason’s newly published version of this story, by contrast, takes a post-modernist approach – casual, playful, earthy, and even scatological. At one point in Mason’s version of The Lost Books of the Odyssey, Odysseus muses about the fact that “I was ideally suited to be a bard, a profession fit only for villeins, wandering masterless men who live at the pleasure of their landed betters, as my father reminded me when I broached the idea. He and his men would say things like, ‘We are here to live the stories, not compose them!’”

And then Odysseus imagines himself as bard, intoning “Sing, Muses, of the wrath of god-like shit-for-brains, hereditary lord of the mighty Coprophagoi [excrement eaters], who skewered a number of other men with his pig-sticker and valued himself highly for so doing,” an obvious, raw satire on the earlier, more poetic translations, such as the one above.

Using the traditional story of the Odyssey as his starting point, Mason gives his own take on various episodes from that epic, jumping around in time and place, changing major aspects of the story, adding new episodes, and providing unique points of view. Odysseus is not an epic hero here. Rather, he is an often arrogant man who loves killing, often acts cruelly, and even makes mistakes, a real man whom Athena abandons for part of the narrative.

In Mason’s version of this epic, Odysseus himself vies for the hand of Helen, not Penelope, and has some success in winning her. After the death of Achilles, Odysseus creates a golem of Achilles out of clay so that Achilles can keep fighting. He tells the tale of Polyphemus, the giant, from Polyphemus’s point of view, that of a peaceful farmer who offers hospitality to th e men whom he finds occupying his cave when he returns home, and the payment they give him. Odysseus also marries during his twenty-year absence from Ithaca. Mason also gives several different accounts of Odysseus’s return home – in one, Penelope is a “shade,” a ghostly presence whom he cannot touch. In another, she has given up waiting for him and found another husband. At other times, she is described as still bedevilled by the suitors. In yet another, Odysseus returns to find his entire city abandoned.

e men whom he finds occupying his cave when he returns home, and the payment they give him. Odysseus also marries during his twenty-year absence from Ithaca. Mason also gives several different accounts of Odysseus’s return home – in one, Penelope is a “shade,” a ghostly presence whom he cannot touch. In another, she has given up waiting for him and found another husband. At other times, she is described as still bedevilled by the suitors. In yet another, Odysseus returns to find his entire city abandoned.

Even Homer himself appears in this novel, lying in a hammock and dreaming of finding a great book. Odysseus, on the other hand, actually finds a copy of the Iliad, written by the gods before the Trojan War, in Agamemnon’s cabin on the ship. Gods and goddesses flit in and out, take the appearance of humans, play tricks, and have love affairs. Tightrope walkers, Alexander the Great, and even the doctors and nurses of a sanatorium appear and disappear.

Though some reviewers say that knowledge of the “real” Odyssey is not a prerequisite to the enjoyment of this book, all the humor depends on that knowledge. The ironies, absurdities, twists and turns, and shifts in point of view need the context of the original epic to have any meaning for the reader. Lovers of postmodern fiction, with its abandonment of boundaries and its open, free-for-all attitudes will find much to love in this novel, which looks at the Odyssey through a new lens.

Graphics: The author’s photo appears on www.fantasticfiction.co.uk. On his Facebook page, Zachary Mason says: “I’m currently the Shade Professor at Magdalen College, Oxford. I have ceased to sound very American, and I certainly don’t sound English – it seems that I am now from nowhere in particular. Luckily, I live half the year on a small island in the Greek archipelago, where no one speaks English well enough to detect my phonetic anomaly.”

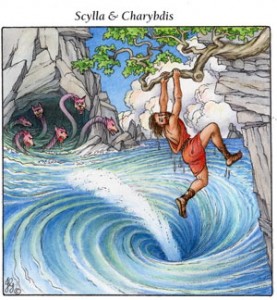

The myth of Scylla and Charybdis is adapted by Amy Friedman and illustrated by Jillian Gilliland on their story-telling site www.uexpress.com.

Scholars have long seen the Odyssey as a record of navigation in the Mediterranean three thousand years ago, and many maps of Odysseus’s journey have been created using the geographical clues from the text. This map appears on many sites and shows Scylla and Charybdis as the Strait of Messina between Sicily and Italy. http://www.learner.org/courses/worldlit/odyssey/explore/