“We’re planning an event in the Athens Metro, it’s been too long since we had a good old-fashioned run-in with the police…Every now and then we smash a shop window or two…but we’re not nearly as active as we used to be…We don’t just wreak havoc indiscriminately, either. And we’ve improved the fonts on our signs. We’re revolutionaries with taste.”—Maria Papamavrou, at age thirty-five.

When my husband and I went to Greece in 1989 on a college-sponsored alumni trip with his favorite art history professor, the professor was very excited to be returning to Greece for the first time since 1967, when the Reign of the Colonels began. Almost twenty years later, as we prepared to arrive, the military dictatorship had ended, and “democracy” had been restored. Times had improved, we thought – until we arrived at the airport in Athens, and found it ringed with tanks! Two recent parliamentary elections had produced no clear mandate for any dominant party, despite the deposing of the king, the election of Prime Minister Nicholas Papandreou, and the mandate for some form of democracy. The police presence in 1989 in every major Athens square emphasized to all of us that the unrest and demonstrations were not over and that democracy in modern Greece was still very much a work in progress. Many of the images I brought back with me – of the Plaka and Syntagma Square, of student demonstrators with their graffiti and placards, and even of the venerable Hotel Grande Bretagne overlooking all the frantic activity in Syntagma Square—came roaring back with this absorbing and fast-paced novel of modern Greece.

When my husband and I went to Greece in 1989 on a college-sponsored alumni trip with his favorite art history professor, the professor was very excited to be returning to Greece for the first time since 1967, when the Reign of the Colonels began. Almost twenty years later, as we prepared to arrive, the military dictatorship had ended, and “democracy” had been restored. Times had improved, we thought – until we arrived at the airport in Athens, and found it ringed with tanks! Two recent parliamentary elections had produced no clear mandate for any dominant party, despite the deposing of the king, the election of Prime Minister Nicholas Papandreou, and the mandate for some form of democracy. The police presence in 1989 in every major Athens square emphasized to all of us that the unrest and demonstrations were not over and that democracy in modern Greece was still very much a work in progress. Many of the images I brought back with me – of the Plaka and Syntagma Square, of student demonstrators with their graffiti and placards, and even of the venerable Hotel Grande Bretagne overlooking all the frantic activity in Syntagma Square—came roaring back with this absorbing and fast-paced novel of modern Greece.

Author Amanda Michalopoulou develops her novel from the point of view of Maria Papamavrou, who is nine in the late 1970s, after the military dictatorship has ended; in her twenties in the 1990s, during a time of unrest; and in her mid-thirties in the early twenty-first century; the novel shifts back and forth among these three time periods. When the novel first opens, Maria, now a thirty-five-year-old teacher in an elementary school, is confronting a rebellious little girl who has just moved to Athens from Paris. Reminded of her own difficult past, Maria then reminisces about her own life when she was a similar age to that of her new student.

The Agios Nikolaus, a Byzantine church built in the 11th century, was near Maria’s school. The girls in her class had their gym classes on the pavement in front of this church, “sit-ups on the sidewalk, between parked cars.”

An adventurous and independent nine-year-old in the late 1970s, Maria has arrived in Athens from Ikeja, Nigeria, where her father has been working. She hates Athens, does not speak the language, though she is officially Greek, and she is the newest student in her school. Her first days of school, filled with humorous detail, endear her to the reader immediately, as she gets into a fight with another student, deals with another who wants to know if a lion ate the missing part of her little finger, and does not understand the expression “fart on my balls.” Her only “friend” is the unseen seventeen-year-old boy who uses her desk for night school and leaves her inappropriate messages. The arrival of Anna Horn, another new student, is the highpoint of her life, however, and when the imperious Anna rudely corrects the teacher, announcing that “We’re not immigrants, we’re dissidents,” Maria feels as if she has found a best friend – until Anna declares that “there are no dissidents in Africa. My mother says you’re racists who exploit black people.” Despite this beginning, Anna and Maria become best friends for life – sort of.

Historical events described within the natural context of Maria’s childhood in Athens become real here – celebrating with Anna the anniversary of the events at Athens Polytechnic, in which the military sent in tanks to kill student occupiers; the warning Anna gives Maria to take off her glasses when there might be “trouble” at a demonstration; the singing of a revolutionary song while older students throw stones near the American embassy; and the girls’ genuine belief that they are the “biggest revolutionaries in all of Athens.” Together they negotiate their lives between Athens and, later, Paris during summer vacations. Still later, as adults, they remain linked not only by friendship but by their shared belief that they, like all the educated college students and young adults with whom they associate, have an obligation to live their philosophies and act, not just pontificate, about “government.”

“The Exarheia area in Athens is notorious. It is portrayed as a hotbed of anarchist radicalism, an area where the very fabric of society is threatened every minute of the day and an area that should be avoided at night.” Quotation from source listed in the photo credits below.

Later, through other shifts in time, Maria describes her life at thirty-five, relating how she met Kayo, the man she lived with when, together, in Geneva in the 1990s, they “overturned the Central Bank Director’s Mercedes and spent two days in jail for it.” Leaving Geneva, they then embarked on other revolutionary activities – shaking the hands of Zapatistas and celebrating the landless people of Bangladesh, before continuing to Nigeria “to shout slogans against the oil companies.” Throughout all this activity, Maria tries to develop her artistic talent, about which Anna has always been jealous. Wildly volatile, even when they were children, their relationship becomes far more complex as they get older. Anna eventually marries and has a child but continues to exhibit her “imperious” attitudes and, more especially, the jealousy which she originally exhibited toward Maria. Though both continue to be interested in “revolutionary” causes, their relationship and common bonds begin to fray as their roles change. Revolutionary activities when these now adult women are in their thirties eventually bring the novel to its climax.

The Acropolis station on the Athens Metro. These statues are copies of the Parthenon Marbles. The originals are still in London.

The lively, conversational point of view, often filled with slang; the casual humor; the girls’ often intense resentments; and many revealing scenes which allow the reader to make his/her own judgments about the increasingly complex characters, enhance the novel and bring its historical time periods to life for an English-speaking audience. Translator Karen Emmerich, who worked directly with the author, is so sensitive to nuances here that there is no feeling that this novel is translated. The reader feels no separation between the author and the translator, as if one person wrote the novel and then translated it into English, with the language and its sentiments perfectly attuned to the action, and the style to the message and themes. The action never flags, and though it takes place in several countries during different time periods, the point of view and the details about the student protests in which the characters involve themselves strike such universal chords that they will feel familiar to most American readers – and certainly to all who are over forty. A rousing coming-of-age novel, Why I Killed My Best Friend explores the never-ending search for values within everyday life while also celebrating the importance of living one’s beliefs.

Photos, in order: The author’s photo appears on http://www.shjcw.gov.cn/

The Agios Nikolaos on the Plaka is from http://www.apostoliki-diakonia.gr

The photo of social unrest in Athens may be found on http://www.theguardian.com/

Exharheia Square, famed for its graffiti and its demonstrations, is also described on this site as a place to avoid at night. http://a-place-called-space.blogspot.com

The Acropolis Metro station features the great sculptures from the Parthenon Marbles. These are, of course, copies. The originals are still in London. http://www.organicallycooked.com

ARC: Open Letter Books

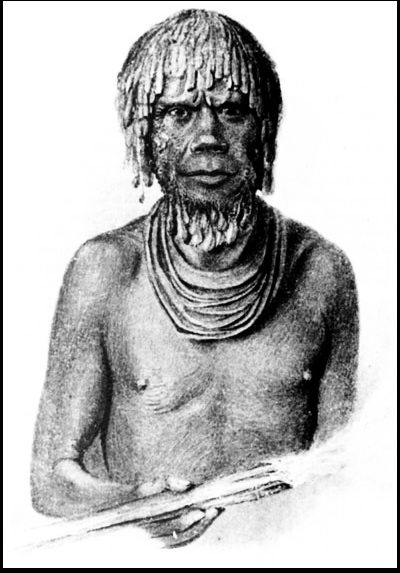

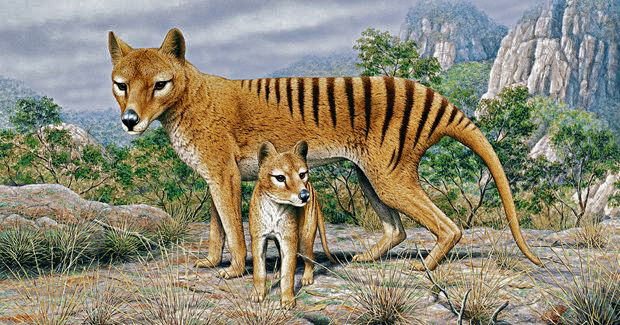

From September, 1829, until early 1831, the British government overseeing the rule of Tasmania as part of its Australian colony, engaged in establishing the shameful “Black Line,” part of its Black War to remove all blacks in Tasmania. Numerous clans of aborigines, who farmed and hunted on “their” Tasmanian lands at will for countless generations learned to hate the whites who appropriated their lands at will, destroyed their farms and habitat, and killed them and their families to take over their traditional lands. Rohan Wilson, a Tasmanian himself, tells the brutal story of the Black Line in the northeast part of Tasmania, in which a white farmer, John Batman, and Manalargena, an aborigine leader, among others, engage in mighty, genocidal battle sanctioned by Colonial Governor George Arthur representing the British crown. As Wilson presents the bloody story of this period, he is sensitive to the historical record, telling of events as they happened, while also paying attention to the incalculable effects of this war on the aborigine people, either through warfare or through the transporting of the few survivors of this war to mainland Australia. His main characters are real and are presented realistically, not as stereotypes of good and evil as they struggle to survive.

From September, 1829, until early 1831, the British government overseeing the rule of Tasmania as part of its Australian colony, engaged in establishing the shameful “Black Line,” part of its Black War to remove all blacks in Tasmania. Numerous clans of aborigines, who farmed and hunted on “their” Tasmanian lands at will for countless generations learned to hate the whites who appropriated their lands at will, destroyed their farms and habitat, and killed them and their families to take over their traditional lands. Rohan Wilson, a Tasmanian himself, tells the brutal story of the Black Line in the northeast part of Tasmania, in which a white farmer, John Batman, and Manalargena, an aborigine leader, among others, engage in mighty, genocidal battle sanctioned by Colonial Governor George Arthur representing the British crown. As Wilson presents the bloody story of this period, he is sensitive to the historical record, telling of events as they happened, while also paying attention to the incalculable effects of this war on the aborigine people, either through warfare or through the transporting of the few survivors of this war to mainland Australia. His main characters are real and are presented realistically, not as stereotypes of good and evil as they struggle to survive.

The castle in this novel, once the home of Count Spork, just outside “the little town where time stood still,” is now a retirement home, residence of elderly pensioners given much freedom to lead comfortable lives, along with a number of old pensioners who need kindly delivered terminal care. “Rediffusion boxes” playing “Harlequin’s Millions” are on the walls everywhere, both inside and outside the castle, and everyone who hears this tune is “entranced” by its “melancholy memory of old times.” The unnamed speaker, the wife of the former owner of a brewery, her husband Francin, and his older brother “Uncle Pepin,” have come to the castle as residents late in life, after losing their brewery when the communists took over in the aftermath of World War II. The speaker, for thirty years an independent and beautiful local actress, has felt at home among the wealthiest residents of their community, and though she is now elderly, toothless, and poor, her changed condition barely fazes her. Still independent in spirit, she embraces her new surroundings, explores them with enthusiasm, and enjoys hearing the stories of other residents at the castle and the history of their much earlier predecessors from as long ago as the seventeenth century.

The castle in this novel, once the home of Count Spork, just outside “the little town where time stood still,” is now a retirement home, residence of elderly pensioners given much freedom to lead comfortable lives, along with a number of old pensioners who need kindly delivered terminal care. “Rediffusion boxes” playing “Harlequin’s Millions” are on the walls everywhere, both inside and outside the castle, and everyone who hears this tune is “entranced” by its “melancholy memory of old times.” The unnamed speaker, the wife of the former owner of a brewery, her husband Francin, and his older brother “Uncle Pepin,” have come to the castle as residents late in life, after losing their brewery when the communists took over in the aftermath of World War II. The speaker, for thirty years an independent and beautiful local actress, has felt at home among the wealthiest residents of their community, and though she is now elderly, toothless, and poor, her changed condition barely fazes her. Still independent in spirit, she embraces her new surroundings, explores them with enthusiasm, and enjoys hearing the stories of other residents at the castle and the history of their much earlier predecessors from as long ago as the seventeenth century.

Norwegian author Jo Nesbo never writes the same book twice, even within his best-selling series of ten Harry Hole thrillers. From

Norwegian author Jo Nesbo never writes the same book twice, even within his best-selling series of ten Harry Hole thrillers. From

Nobel Prize winner Mario Vargas Llosa continues to speak out politically in yet another realistic and uncompromising novel set in his home country of Peru. In this novel, he brings the reader face to face with the horrors of the Shining Path (Sendero Luminoso), a Maoist terror group operating in the mountains of Peru from the early 1980s to the mid-1990s, with seemingly few direct challenges from the government. The novel’s sense of immediacy, enhanced by vivid descriptions of real events affecting real people, provides a close-up look at the tactics, including massacres, used by the Shining Path in the central and southern mountains of Peru, where they attacked indigenous Indian peasants, all foreigners, all educated Peruvians working to improve the lives of the peasants by providing better services, and anyone representing the government or police.

Nobel Prize winner Mario Vargas Llosa continues to speak out politically in yet another realistic and uncompromising novel set in his home country of Peru. In this novel, he brings the reader face to face with the horrors of the Shining Path (Sendero Luminoso), a Maoist terror group operating in the mountains of Peru from the early 1980s to the mid-1990s, with seemingly few direct challenges from the government. The novel’s sense of immediacy, enhanced by vivid descriptions of real events affecting real people, provides a close-up look at the tactics, including massacres, used by the Shining Path in the central and southern mountains of Peru, where they attacked indigenous Indian peasants, all foreigners, all educated Peruvians working to improve the lives of the peasants by providing better services, and anyone representing the government or police.