“I am going to reveal something which you suspect [your Honour], something which you don’t want to admit and which torments you in secret…You are afraid of yourself, of a certain frenzy which might take possession of you… We are almost identical men, your Honour…and I acted with premeditation, in full consciousness of my act.”

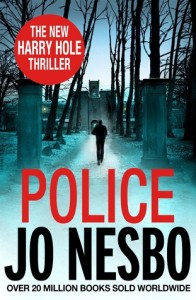

Belgian author Georges Simenon (1903 – 1989), a prolific author, published two hundred novels and over one hundred fifty novellas during his long career, most of them involving mysteries of some sort. Though he is the author of the Inspector Maigret series, hugely successful in the film versions and TV series in addition to the novels, he was particularly proud of his much more serious novels, his “roman durs,” psychological novels in which he reveals his interest in how ordinary people deal with the many shocks and betrayals of their personal lives. Act of Passion, published in 1947, is one of these romans durs, a novel about which critic Roger Ebert has asked, “Why is there no sense at the end [of the novel] that justice has been done, or any faith that it can be done?…There are questions for which there are no answers. Act of Passion is essentially a question posing as an answer.”

Belgian author Georges Simenon (1903 – 1989), a prolific author, published two hundred novels and over one hundred fifty novellas during his long career, most of them involving mysteries of some sort. Though he is the author of the Inspector Maigret series, hugely successful in the film versions and TV series in addition to the novels, he was particularly proud of his much more serious novels, his “roman durs,” psychological novels in which he reveals his interest in how ordinary people deal with the many shocks and betrayals of their personal lives. Act of Passion, published in 1947, is one of these romans durs, a novel about which critic Roger Ebert has asked, “Why is there no sense at the end [of the novel] that justice has been done, or any faith that it can be done?…There are questions for which there are no answers. Act of Passion is essentially a question posing as an answer.”

Ebert is not being coy. The main character here, a physician named Charles Alavoine, admits from the outset that he is guilty of premeditated murder, but he has had a good relationship with this magistrate, who investigated his story and interviewed the crime’s witnesses over the course of six weeks, and he feels that this magistrate, who is assigned only to investigate the case and not to try it, will understand him if the magistrate learns about his inner life. If he can understand that, then, Alavoine believes, the magistrate will understand why he committed murder. This is essential to Alavoine because “to understand him would be to forgive him,” not with any hope that he might be cleared or excused of his actions, but because he believes that by committing this murder he has permanently freed himself and the victim from the torments inflicted by phantoms. He sees the magistrate as a kindred spirit, and “Since I had the courage to go to the bitter end, why not, in turn, have the courage to try to understand me?” he challenges the magistrate. By killing his lover, he believes he has “delivered her,” allowing their love to last forever, unsullied. “Until someone has admitted [that I acted with premeditation], I shall be alone in the world.”

What follows is a thorough investigation of the doctor’s life, told from the doctor’s own point of view. He is the first generation of his family to have become educated and successful, and he notes that when his mother had to testify at the trial, she was “ashamed. Not ashamed of me…but ashamed of being target of all those eyes, ashamed of disturbing such important persons.” He remembers the testimony regarding the death of his first wife, who died two hours after giving birth to their second child, and he blames himself for her death. His desire for a big, healthy son had led him to ignore his wife’s thinking, and when she eventually produced their second baby, who weighed just short of twelve pounds, she died as a result. His second wife, the “serene” Armande has testified in a controlled and dignified manner, befitting, he believes, the rather cold approach she has always had toward life, a life in which she has taken complete control of his home and family, at the expense, sometimes, of his doting mother, while he himself feels an increasing sense of emptiness in their relationship.

It is these memories of Armande which lead him to ask the magistrate to imagine that “all at once, the shadow accompanying you [during your walk] disappears…And suddenly there you are in the street without a shadow…You begin to feel yourself all over…You turn on your heel and look down, there is no dark spot on the bright stones of the pavement.” Though the world is full of reassuring shadows, the dreamer is “seized with anguish…Can you imagine the anguish of wandering alone without a shadow in a world where everybody else has one?” The symbolism is obvious. Except for one brief encounter many years ago with a young woman in Caen, Alavoine has never even come close to feeling real love, and the emptiness is overwhelming him. That soon changes.

The doctor, successful in his field, has far less knowledge of himself and about what constitutes success in personal relationships than he believes he does, and it is this lack of awareness and lack of experience which set him up for the disaster which is his own unmaking. Ironically, he believes it is a triumph, not just for him, but for his lover (and victim) as well. Limited in emotional insights, Alavoine makes broad ethical statements, and tries to “define,” rather than to feel and express. He can remember the past in enormous detail, when it comes to places and appearances, but he has little insight. He defines love in terms of “the need of nearness,” and “the thirst to explain” but says little about real feeling, the idea of putting someone else’s desires and needs ahead of one’s own. The author, too, seems to have absorbed some of these attitudes in the writing of this book. By presenting the killer’s thinking in great detail, he tries to create a feeling for the killer on the part of the reader, believing it possible to make the reader share the killer’s feelings. He almost succeeds.

At one point Alavoine suggests that he and his beloved go to the Vincennes Zoo, where, in a darkly ironic twist, a pair of loving chimpanzees serve as a model of behavior

As he develops Alavoine’s psyche, Simenon cannot disguise Alavoine’s arrogance. Alavoine seems to believe that his expertise in one area of life, his career, makes him an expert in other areas of life, such as love and its mysteries. Slowly and inevitably, the author sets up Alavoine and his lover, and it becomes sadly ironic to watch as Alavoine, firmly convinced that his behavior is good and right, reveals how limited he is in true understanding. As the doctor and his lover mover closer and closer to their destiny, the reader follows along, always wondering how much the “we” of the narrative really involves a sense of sharing and how much it may be the doctor imposing his will on his naïve partner. Ultimately he declares, for better or worse, that “I shall live in her, with her, for her, as long as I possibly can, and if I imposed upon myself that sort of circus which was called a trial, it was so that she, no matter what the cost, may continue to live in someone…We wanted the totality of love.”

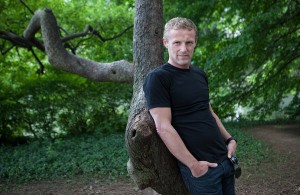

Photos, in order: The author’s photo appears on http://www.ladepeche.fr

The author’s birthplace in Liege is depicted here: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/. Photo by Flamenc. Later he makes a trip here to visit the places where his lover grew up.

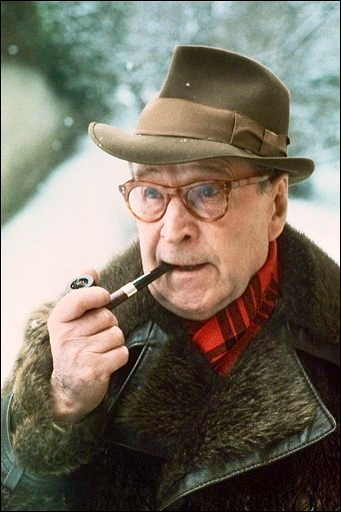

Michael Gambon played the role of Maigret, a Simenon creation, for several years in the 1990s. http://tvbeatsmovies.blogspot.com

The loving chimpanzees at the Vincennes Zoo serve as a model for Alavoine and his lover, at one point in the novel. http://www.hsi.org/

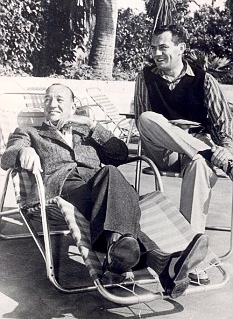

A professional dancer from the age of eleven, Noel Coward (1899 – 1973) spent the rest of his life in “show business” as a playwright (of thirty-nine plays), composer (of over three hundred songs and sixteen musicals and operettas), film maker (of fifteen adaptations of his plays), and actor-director-producer connected with two dozen additional productions. Now, however, it is 1971, as this novel about his life opens, and he is seventy-two and dealing with an endless series of heart and lung problems, no doubt exacerbated, if not caused, by his persistent smoking. (So constant was the smoking that when I was looking for a portrait of him for this review, I could find only a handful of pictures without the ubiquitous cigarette.) Living for much of the year at Firefly, his Jamaican studio and retreat at the top of Captain Morgan’s Lookout toward ocean, he is attended by Patrice, a young Jamaican in his twenties who is particularly excited by this temporary position, since it will allow him, he hopes, to obtain a reference from The Boss so that he can apply for a job at the Ritz in London as a “silver service waiter.” He has no training or experience for this position, but he is desperate for the chance to succeed.

A professional dancer from the age of eleven, Noel Coward (1899 – 1973) spent the rest of his life in “show business” as a playwright (of thirty-nine plays), composer (of over three hundred songs and sixteen musicals and operettas), film maker (of fifteen adaptations of his plays), and actor-director-producer connected with two dozen additional productions. Now, however, it is 1971, as this novel about his life opens, and he is seventy-two and dealing with an endless series of heart and lung problems, no doubt exacerbated, if not caused, by his persistent smoking. (So constant was the smoking that when I was looking for a portrait of him for this review, I could find only a handful of pictures without the ubiquitous cigarette.) Living for much of the year at Firefly, his Jamaican studio and retreat at the top of Captain Morgan’s Lookout toward ocean, he is attended by Patrice, a young Jamaican in his twenties who is particularly excited by this temporary position, since it will allow him, he hopes, to obtain a reference from The Boss so that he can apply for a job at the Ritz in London as a “silver service waiter.” He has no training or experience for this position, but he is desperate for the chance to succeed.

With this quotation, epitomizing the attitudes and ideas in this collection, IMPAC Dublin Award winner Kevin Barry shows his complete mastery of the short story form, presenting startling, eye-opening stories of love and loss, hope and despair, and acceptance and resistance. Many of the characters here reflect an almost religious belief that misery, for whatever reason, need be only temporary if one has the strength and will to search within. As they confront their challenges, Barry draws in the reader, inspiring hope that these individuals will prevail, either alone or with the help of friends. The characters spring from the page, face a demon or two, and then retire to small lives lived between the cracks of a larger society which does not notice them. The “unremarkable” people whose stories are told here often overcome challenges of universal significance, giving a resonance and a sense of thematic unity which is often lacking in other collections. This is not to say that these are “easy” or “comfortable” stories for the reader. Most of the characters are at least a little bit “off-kilter,” their problems at least a little bit beyond those of most readers, and their lives at least a little bit more bizarre than most of us who are reading about them. Unfortunately, some of these characters are also too weak to see hope; some do not have the energy or desire to change; and some are so dependent on others for their emotional stability that they are not equipped to face the present, much less the future. Barry shows them all as they face turning points in their lives, for better or worse.

With this quotation, epitomizing the attitudes and ideas in this collection, IMPAC Dublin Award winner Kevin Barry shows his complete mastery of the short story form, presenting startling, eye-opening stories of love and loss, hope and despair, and acceptance and resistance. Many of the characters here reflect an almost religious belief that misery, for whatever reason, need be only temporary if one has the strength and will to search within. As they confront their challenges, Barry draws in the reader, inspiring hope that these individuals will prevail, either alone or with the help of friends. The characters spring from the page, face a demon or two, and then retire to small lives lived between the cracks of a larger society which does not notice them. The “unremarkable” people whose stories are told here often overcome challenges of universal significance, giving a resonance and a sense of thematic unity which is often lacking in other collections. This is not to say that these are “easy” or “comfortable” stories for the reader. Most of the characters are at least a little bit “off-kilter,” their problems at least a little bit beyond those of most readers, and their lives at least a little bit more bizarre than most of us who are reading about them. Unfortunately, some of these characters are also too weak to see hope; some do not have the energy or desire to change; and some are so dependent on others for their emotional stability that they are not equipped to face the present, much less the future. Barry shows them all as they face turning points in their lives, for better or worse.

In this unusual metafictional novel of the Spanish Civil War, author Javier Cercas experiments with the voice of his main character and with the form of this novel, which he describes as “a compressed tale except with real characters and situations, like a true tale.” The unnamed speaker, a contemporary journalist in his forties, is investigating the story of Rafael Sanchez Mazas, a “good, not great” writer of the 1930s, who, in the final days of the Civil War (1936 – 1939) escaped a firing squad and lived to play a role in Franco’s Nationalist government.

In this unusual metafictional novel of the Spanish Civil War, author Javier Cercas experiments with the voice of his main character and with the form of this novel, which he describes as “a compressed tale except with real characters and situations, like a true tale.” The unnamed speaker, a contemporary journalist in his forties, is investigating the story of Rafael Sanchez Mazas, a “good, not great” writer of the 1930s, who, in the final days of the Civil War (1936 – 1939) escaped a firing squad and lived to play a role in Franco’s Nationalist government.