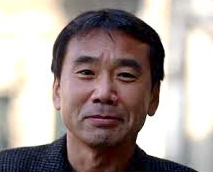

Note: Haruki Murakami is WINNER of many international prizes, including the Premio Internacional Catalunya in 2011. He donated the eighty thousand Euros from this prize to victims of the March 11, 2011, earthquake and tsunami, and to those affected by the Fukushima nuclear disaster.

“For the five months after he returned to Tokyo, Tsukuru lived at death’s door…All around him, for as far as he could see, lay a rough land strewn with rocks, with not a drop of water, nor a blade of grass. Colorless, with no light to speak of. No sun, no moon or stars. No sense of direction, either… A remote border on the edges of consciousness.”

In his newest novel, Haruki Murakami once again explores two of his major themes, alienation and isolation as they affect the life of a sensitive and introverted character. Tsukuru Tazaki, age twenty as the novel opens, has always regarded himself as “colorless” in relation to his group of four long-time friends, two young women and two young men who have been his constant companions throughout high school in Nagoya. His friend Aka has always had the best grades in school and is a ferocious competitor; Ao, a forward on the rugby team, was rugby captain in his senior year, and like Aka has an intense desire to win. One of the women, Kuro, though not beautiful, is charming, independent and curious, with a quick tongue to match her quick mind, while Shiro, the other woman, is tall, slim, and beautiful, someone who enjoys teaching piano to children but does not enjoy being the center of attention. Tsukuru has always been secretly attracted to her.

In his newest novel, Haruki Murakami once again explores two of his major themes, alienation and isolation as they affect the life of a sensitive and introverted character. Tsukuru Tazaki, age twenty as the novel opens, has always regarded himself as “colorless” in relation to his group of four long-time friends, two young women and two young men who have been his constant companions throughout high school in Nagoya. His friend Aka has always had the best grades in school and is a ferocious competitor; Ao, a forward on the rugby team, was rugby captain in his senior year, and like Aka has an intense desire to win. One of the women, Kuro, though not beautiful, is charming, independent and curious, with a quick tongue to match her quick mind, while Shiro, the other woman, is tall, slim, and beautiful, someone who enjoys teaching piano to children but does not enjoy being the center of attention. Tsukuru has always been secretly attracted to her.

In contrast to his friends, Tsukuru is an indifferent student with little interest in sports, the arts, or any hobbies. In fact, as he points out himself, “There was not one single quality he possessed that was worth bragging about or showing off to others…Everything about him was middling, pallid, lacking in color.” And his name is quite literally colorless: All his friends’ names contain a color in their meanings – red, blue, white, black, with a later acquaintance having a name meaning “gray” – but Tsukuru’s name has no such colorful connotation, the meaning of his name being associated with “making” or “creating.”

Years later, when he is thirty-six, Tsukuru lives alone in a small apartment, with no real friends, few outside interests, and the overwhelming feeling that something is not quite right about him, all this stemming from a traumatic event which occurred to him after he left his close friends for university in Tokyo while they stayed in Nagoya at “less prestigious schools.” Tsukuru might have stayed, too, had it not been for his lifelong ambition to study railroad engineering, and the only place he could do that was in Tokyo.

His first year in Tokyo he does see his friends in Nagoya on vacations and they do telephone, but suddenly, without warning after his sophomore year, his friends inexplicably stop returning his calls and ask him not to call them again, events which leave him on the verge of suicide. Even after finally emerging from his suicidal depression, graduating from university, and beginning a job designing railway stations, he remains traumatized by these events from the past. Eventually, he meets Haida, another recent graduate, who is a kind of alter-ego, a man committed to the arts, classics, Shakespeare, and music, who teaches him new ways of thinking and seeing the world. He often plays a recording of Liszt’s “Le Mal du Pays” from his “Years of Pilgrimage” suite in Tsukuru’s apartment as they talk.

Shinjuku Station, where Tsukuru works, is the busiest station in the world, wtih 3.64 million passengers using it every day!

Over the ensuing years, people come and go in Tsukuru’s life without leaving much impression, until he, at age thirty-six, meets Sara, age thirty-eight. Sara will not have a relationship with him, she says, until he confronts the people in Nagoya who used to be his friends and asks them directly what really happened, instead of simply accepting all the horrors that he imagines might have happened. Sara, a travel agent, is willing to help him get started, and Tsukuru has no choice but to begin his pilgrimage by visiting these people from his past and coming to terms with his amorphous guilt for his unknown “crime.” He does not know if his sense of isolation and alienation have a real cause, or if they are simply a natural outgrowth of the fact that he is not a very interesting person. Until he begins his quest and actually meets his former friends, however, he has no idea how much his “reality” may have been the result of faulty perceptions, ignorance, and or victimization by “friends” who acted in a way they thought was honorable at the time.

One of Tsukuru’s former friends now lives in Finland in a lakeside cottage resembling this one in Hameenlinna.

Murakami creates a straightforward novel which captures the reader’s interest on the level of plot, while also fleshing it out with philosophical and metaphysical discussions, psychological insights, and literary and musical references – from Liszt’s “Years of Pilgrimage” to Thelonius Monk’s “Round Midnight,” and even Elvis Presley’s hit from 1963, “Viva Las Vegas.” Tsukuru’s first trip outside Japan to visit one of his old friends, now in Finland, expands the focus and gives it a world view, while also introducing commentary on the value of art, to which that school friend and spouse have now dedicated their lives. His other two friends are successful entrepreneurs. Intimate friendships change as people change, and as ideas and reality and one’s perceptions of it change. Lives like Tsukuru’s, the author shows us, are often a series of missed opportunities. As one of the old friends tells him, “ It wasn’t a waste for us to have been us – the way we were together, as a group. I really believe that. Even if it was only for a few short years…We survived. You and I. And those who survive have a duty. Our duty is to do our best to keep on living. Even if our lives are not perfect.”

This straightforward novel is fun to read, and it moves quickly, lacking the pervading existentialism, surrealism, and magical elements which Murakami often includes in his novels. Instead, he focuses on presenting simplified (though in no way “simplistic”) themes and their corollaries as seen in the life of a “colorless man.” The one caveat I have here is that there are several spots in which either the author or the translator gives way to a kind of preachiness and the use of aphorisms, i.e., “Ideas are like beards. Men don’t have them till they grow up.” These are more than balanced, however, by some lovely, even lyrical descriptions of the countryside, and by Tsukuru himself, who, despite his “colorless” character manages to strike chords of familiarity with the reader as he struggles to discover who he is.

ALSO by Murakami: FIRST PERSON, SINGULAR (stories)

Photos, in order: The author’s photo is from http://freewilliamsburg.com/

The photo of Tokyo University appears on http://www.law.harvard.edu/

Shinjuku Station, where Tsukuru works, serves 3.64 million passengers every day and is the highest volume railroad station in the world. http://patriciaurizar.blogspot.com/

The cottage in Hammenlinna, resembling the one occupied by a former friend of Tsukuru, may be found here: http://www.campaya.co.uk/

The spouse of Tsukuru’s old friend specialized in pottery made in pastel colors, while Tsukuru’s friend’ pottery is more texture, less colorful. Pottery found here: http://gatherblog.blogspot.com Photo by HannaKruse: http://www.hannakruse.com/

The music of Liszt’s Years of Pilgrimage Suite echoes throughout the novel:

In a novel that is otherwise devoid of poetry, author Adriana Lisboa recreates the perennial search for “family” and “home” by a thirteen-year-old girl who has left Rio de Janeiro in search of her biological father in the United States, following the death of her mother. In starkly realistic and highly descriptive language, the life of Evangelina, known as Vanja, opens and shuts like the “crow-blue” mussel shells she remembers so vividly from Copacabana Beach in Rio. When Vanja arrives in Lakewood, Colorado, where her legal father lives, she discovers a place that is completely alien in terms of weather, wind, elevation, and culture. Though her beloved sea is over a thousand miles away, Vanja takes some comfort in seeing the “shell-blue crows” which fly over Denver, however – new birds that she sees in the open spaces and unfamiliar trees of her new home, birds that are independent, resourceful, and long-lived, even within this urban setting.

In a novel that is otherwise devoid of poetry, author Adriana Lisboa recreates the perennial search for “family” and “home” by a thirteen-year-old girl who has left Rio de Janeiro in search of her biological father in the United States, following the death of her mother. In starkly realistic and highly descriptive language, the life of Evangelina, known as Vanja, opens and shuts like the “crow-blue” mussel shells she remembers so vividly from Copacabana Beach in Rio. When Vanja arrives in Lakewood, Colorado, where her legal father lives, she discovers a place that is completely alien in terms of weather, wind, elevation, and culture. Though her beloved sea is over a thousand miles away, Vanja takes some comfort in seeing the “shell-blue crows” which fly over Denver, however – new birds that she sees in the open spaces and unfamiliar trees of her new home, birds that are independent, resourceful, and long-lived, even within this urban setting.

The ninth year of the Fascist Era, 1931, is almost over, and the residents of Naples, at least those who have managed to keep food on the table, are getting ready for Christmas. Within this setting Maurizio de Giovanni develops his fifth novel in which Commissario Ricciardi is challenged by a terrible murder, the slashing and stabbing deaths of a husband and wife from a wealthy family. The husband Emanuele Garofalo is a rising star as a Centurion in a fascist-inspired seaport militia, which governs the port, its boats, its fishermen, and all the fish being brought in to market. The possibilities for corruption and graft are enormous, and Garofalo, who acquired his position by making false claims against his boss, is up to his neck in criminal activities. The bodies of the couple are found when the zampognari, two young men who help celebrate the season by playing the Neapolitan bagpipe, come to the Garofalos’ house to play for them in the lead-up to Christmas. Terrified, the young men immediately call the police, and Commissario Ricciardi and Brigadier Maione dutifully appear.

The ninth year of the Fascist Era, 1931, is almost over, and the residents of Naples, at least those who have managed to keep food on the table, are getting ready for Christmas. Within this setting Maurizio de Giovanni develops his fifth novel in which Commissario Ricciardi is challenged by a terrible murder, the slashing and stabbing deaths of a husband and wife from a wealthy family. The husband Emanuele Garofalo is a rising star as a Centurion in a fascist-inspired seaport militia, which governs the port, its boats, its fishermen, and all the fish being brought in to market. The possibilities for corruption and graft are enormous, and Garofalo, who acquired his position by making false claims against his boss, is up to his neck in criminal activities. The bodies of the couple are found when the zampognari, two young men who help celebrate the season by playing the Neapolitan bagpipe, come to the Garofalos’ house to play for them in the lead-up to Christmas. Terrified, the young men immediately call the police, and Commissario Ricciardi and Brigadier Maione dutifully appear.

In this final book of his Copenhagen Quartet, author Thomas E. Kennedy creates yet another vibrant portrait of life in Copenhagen, the city which has been his own home for the past thirty years. Each of the four novels in the quartet focuses on a different aspect of the city’s life as Kennedy has observed it there as an American expatriate. Each is written in a different literary style, and each is set during a different season, with different characters.

In this final book of his Copenhagen Quartet, author Thomas E. Kennedy creates yet another vibrant portrait of life in Copenhagen, the city which has been his own home for the past thirty years. Each of the four novels in the quartet focuses on a different aspect of the city’s life as Kennedy has observed it there as an American expatriate. Each is written in a different literary style, and each is set during a different season, with different characters.