Note: As I was doing research for a paper to be delivered next month, it struck me that some other readers, perhaps in other parts of the country or from other nations, might find some aspects of this history as fascinating as I did. This colony was settled at almost the same time as Plymouth, but was very different.

“From the commencement of this volume, we have been kindly carried by the hand of Providence to its completion. While it has been in progress, even some, who expected to peruse its pages, have been called to their great account. This is an emphatic admonition to us, that, while we look back on the past and collect its details…we should not forget the uncertainty, which hangs upon the future of all our secular plans, purposes, and anticipations.” Joseph B. Felt, Introduction to this History, 1834.

Joseph B. Felt’s History, written in 1834 has been republished several times, most recently in 2011.

Though most Americans are familiar with the story of America’s poor pilgrims who made the dangerous voyage across the Atlantic Ocean to settle in Plymouth in 1620, few outside of Massachusetts are aware of the nearly contemporaneous Ipswich colony which began north of Boston in 1629, a colony dramatically different from Plymouth. Joseph B. Felt’s history of three towns, once the single town of Ipswich in the Massachusetts Bay Colony, makes Ipswich come alive. His history is not only good, it’s exciting, filled with unusual and well preserved information about a settlement which began just a few years after the Plymouth colony. Here Felt traces the Ipswich colony from its founding in 1629 to 1834, creating an incomparable resource covering over two hundred years. He himself, a Congregational minister in what is now Hamilton, from 1824 – 1833, cared greatly about preserving its history, and in writing this book he was clearly conscious of the importance of explaining the thinking of the period and its customs for future generations.

John Winthrop, Ipswich settler, and first governor of Massachusetts Bay (1637 – 1640)

Charter of Massachusetts Bay. The settlers of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, in contrast to Plymouth, were often well-to-do second or third sons of successful Englishmen. Under England’s inheritance laws, it was the first son who inherited his father’s estate. The other sons would be ineligible and in most cases would be unable to live the comfortable lives they were used to in their father’s house. Under the charter of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, “adventurers,” willing to settle there, were offered opportunities never available to them in England – or available to the pilgrims who settled in Plymouth. As Felt explains: Under the terms of passage, any man who came to Ipswich would be granted fifty acres of land. If he were to pay his own fare, however, he would be granted a hundred acres, and a hundred more acres for every additional person whose fare he paid. A man bringing his wife and a child would automatically get three hundred acres, if he paid all the fares, and, under these terms, a few of the wealthiest “adventurers” to Massachusetts Bay acquired over a thousand acres.

Religion: The colony was a theocracy of Congregational believers, all of whom took an oath as to their belief and intention to follow the precepts of their church. Quakers and those of other religions were not allowed in the community.

Location of houses: For the first generation in the colony, all houses had to be built within half a mile of the meeting house, though residents were permitted to develop farms in the outskirts of town. Within a generation, the colony’s common grazing lands had been exhausted by overuse, and Ipswich permitted houses to be farther from the meeting house, eventually establishing three separate parishes, each with its own meeting house. Joseph Felt, himself a minister of one of these parishes, was in close touch with residents from throughout the town, but especially from the area which became the Third Parish, south of Ipswich.

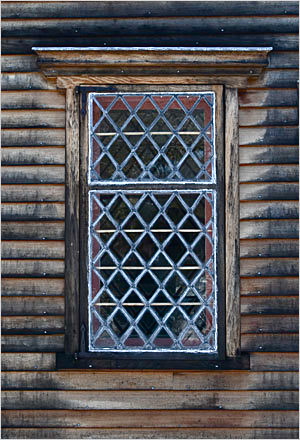

Building style: Unlike the small, simple cottages, often a single room with a low ceiling, which the early pilgrims built in Plymouth, the houses in Ipswich were often large, with many rooms and surprisingly high ceilings, befitting the status of some of the large landowners, who became as successful in Ipswich as they had hoped they would be. As building styles changed and building methods improved, homeowners continuously improved their houses. The original leaded glass windows of the seventeenth century, which opened outward, began to be replaced by the beginning of the eighteenth century with new sash windows, usually spaced so that there would be two sash windows on each outside wall, instead of one, allowing more light.

Marriages: Not surprisingly, marriages were regarded as contracts between families of similar status, and marriages involving a wide disparity in ages were not unusual in order to preserve family wealth. In one marriage in Ipswich, the groom was thirty-seven years older than his bride. The formula that evolved regarding appropriate marriages suggested that a prospective wife should have her own wealth equivalent to half that of her husband to bring to the marriage. When the marriage took place, he became the owner of all her lands.

Tracing genealogies: Tracing genealogies is a daunting prospect for some families, even with all the information contained in this book. In Ipswich it was not unusual for two brothers to come to the colony and for them all to repeat names. John and Matthew, brothers, would often name their sons John and Matthew, and their sons would do the same, so that by the third generation, if all the brothers survived, these two brothers might have produced twelve Johns and Matthews all with exactly the same name. They did not use middle names during the first few generations in the colony, and people with the same names were sometimes distinguished by their rankings in the militia – corporal, major, captain, etc. – but as these rankings also changed, that sometimes added even more to the confusion in tracing families. It was also common that when a child died, successive children would be given the names of the children who had died. In one family, three different children were named Mary within twelve years.

Choate House, Hog Island, Ipswich, built 1730. Photo by Cody Carlson. Note change to sash window style. Double click to enlarge.

Felt does a remarkable job of providing everything that it is possible to know about the Ipswich colony from 1630 to 1834 – the people, places, customs, and changes which occurred during that time. Almost four hundred years have now passed since the founding of the Ipswich colony, yet many of the same names are still active in the community, many of the seventeenth century buildings still exist (clustered on the hill where the meeting house was located), and some estates still contain hundreds of acres, even now. In recent years, much been done to preserve the historic character of the community, with historic districts, historical commissions, National Register listings, and the establishment of a greenbelt association which preserves open land by allowing heirs of the land to continue using it as long as it is not subdivided, developed, or sold. I finished this book in awe of the resilience of these three communities, each of which was part of the original colony but which, over nearly four hundred years, has developed unique qualities.

Hand-blown glass windows, Goodale House. Photo by Mark Wilson

Photos, in order: The portrait of John Winthrop, painter unknown, appears on http://en.wikipedia.org/

The three photos of the Isaac Goodale House from 1668 are from http://www.boston.com/ Photos by Mark Wilson.

The Choate House from Hog Island, Ipswich, 1730. Photo by Cody Carlson: http://commons.wikimedia.org