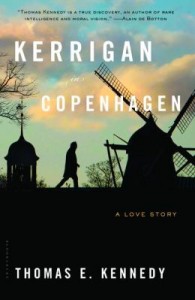

Note: Thomas E. Kennedy was WINNER of the Frank Expatriate Writing Award in 2002, his citation saying, “Kennedy has done for Copenhagen what Joyce did for Dublin.”

“Kerrigan Kerrigan

Whither rovest thou?

What you seek, you shall not find

Rather, let full be your belly.

Make merry day and night and forget the darkness.”

Wanting to find serenity, a new life, and maybe even a new love, Kerrigan has arrived in Copenhagen, the birthplace of his mother, hoping for changes in his own life, but “like Gilgamesh he kept finding instead a Divine Alewife who filled his glass and chanted” words like those above, urging him, instead, to eat, drink, and be merry. Kerrigan, who has a Ph.D. in literature, experienced a personal disaster three years ago, one in which he lost his young wife, his three-year-old daughter, and an unborn child, and he has come to believe that “that is how all stories end. With the naked, withered Christmas tree tilted against the trash barrel.” Now, as the new millennium is about to arrive, Kerrigan plans to “clothe himself in [Copenhagen’s] thousand years of history, let its wounds be his wounds, let its poets’ songs fill his soul, let its food fill his belly, its drink temper his reason, its jazz sing in the ears of his mind, its light and art and nature and seasons wrap themselves about him and keep him safe from chaos.”

Wanting to find serenity, a new life, and maybe even a new love, Kerrigan has arrived in Copenhagen, the birthplace of his mother, hoping for changes in his own life, but “like Gilgamesh he kept finding instead a Divine Alewife who filled his glass and chanted” words like those above, urging him, instead, to eat, drink, and be merry. Kerrigan, who has a Ph.D. in literature, experienced a personal disaster three years ago, one in which he lost his young wife, his three-year-old daughter, and an unborn child, and he has come to believe that “that is how all stories end. With the naked, withered Christmas tree tilted against the trash barrel.” Now, as the new millennium is about to arrive, Kerrigan plans to “clothe himself in [Copenhagen’s] thousand years of history, let its wounds be his wounds, let its poets’ songs fill his soul, let its food fill his belly, its drink temper his reason, its jazz sing in the ears of his mind, its light and art and nature and seasons wrap themselves about him and keep him safe from chaos.”

Kerrigan’s sense of his own personal mission directly parallels that of author Thomas E. Kennedy as he writes about Kerrigan in this third novel of his “Copenhagen Quartet.” An American expatriate who grew up in New Jersey but who has lived in Copenhagen for over thirty-five years, Kennedy creates a novel focused on what is most essential, not just relative to Kerrigan, but to the city itself at the beginning of the twenty-first century, filling it with people and events that have been part of Copenhagen’s history: the authors who have celebrated the city and authors who have been part of Kerrigan’s own history (and that of his Irish father); the sculptors and painters who have created uncountable monuments of public art on the city’s streets; and the musicians, many of them jazz musicians from the United States, who, over the years, have found an enthusiastic audience in Copenhagen’s concert halls, bars, and clubs. For Kennedy, as he relates the story of Kerrigan, Copenhagen becomes the equivalent of the Dublin which Stephen Dedalus explores in James Joyce’s Ulysses.

The exterior painting of the Palace Theater, which Kerrigan visits on his first walk around Copenhagen, was designed by Poul Gernes. (More info on Gernes in the photo credits.)

Kerrigan’s academic research has made him an expert in “verisimilitude,” the appearance of reality that allows “a writer [to create] a credible illusion to get the reader to “suspend disbelief enough long enough to listen and experience what the writer wants to transmit. Beneath the illusion, if the writer is serious, lies the stuff of truth, of a deeper reality, that probably has little to do with the trappings of everyday life that were used to build the illusion…Fiction, even the most realistic-seeming fiction, is not existence, but about existence…For example, Kafka uses sensory images to make us believe, or at least accept, the preposterous notion that Gregor Samsa has turned into a cockroach, and because we believe that for a little while, we experience some deep mystery of existence.” Kerrigan’s expertise in “verisimilitude” becomes ironic in view of his own difficulties seeing who he really is.

The immediate task for Kerrigan is not erudite. Having hired an Associate who is a freelance research secretary, a woman of about his own age (he is fifty-six), Kerrigan will visit and evaluate the bars and cafes in Copenhagen. He must “select a sampling of one hundred of the best, most historic, [and] most congenial from among Copenhagen’s 1525 serving houses and write them up for one of a one-hundred volume travel guide: The Great Bars of the Western World.” He admits, however, that “he does not wish the book to be written. He wants only to research it. Forever. For whatever forever remains to him.”

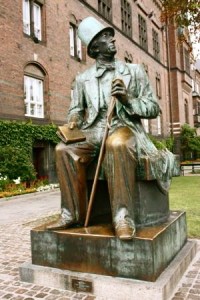

Hans Christian Andersen, socially inept, found his private life unfulfilling. An interesting anecdote appears in the photo credits.

As Kerrigan’s quest unfolds, with the assistance of his Associate, whose real name is finally revealed as “Annelise,” the reader gradually begins to understand the circumstances of Kerrigan’s marriage and the loss of his family. In the meantime, Kerrigan is coming to understand and appreciate his Associate in ways new to him, though his dependence on alcohol complicates his ability to recognize and communicate that fact. All this is hidden within mountains of information about the authors, musicians, artists, and historical figures who are part of the Copenhagen that Kerrigan knows.

Kerrigan carries with him a copy of Joyce’s Finnegan’s Wake, and he mentions that Joyce, who visited Copenhagen in 1936, believed that he had some Danish blood. He pays tribute to Tom Kristensen, “one of Denmark’s great unknown sons,” whose work he especially appreciates, to Peter Hoeg for his book Borderliners, to Dan Turell, who seems to be one of the author’s own favorites, and to Hans Christian Andersen, whose writing career reached its pinnacle with the publication of his stories. Goethe, Sir Walter Scott, Robert Louis Stevenson, Ernest Hemingway, Soren Kierkegaard, Frank O’Hara, Guy de Maupassant, Charles Dickens, John Steinbeck, J.P. Donleavy, Karen Blixen (Isac Dinesen), and many others also add color and insights in the novel.

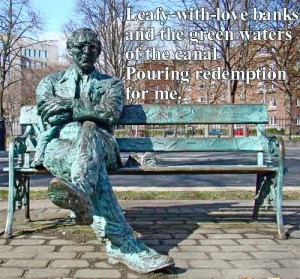

In Dublin, Patrick Kavanagh is second only to William Butler Yeats in popularity as an Irish poet. Double click on photo to read the quotation.

Dozens of Copenhagen statues and memorials and their artists receive attention. Singled out among musicians (as he was also in Kennedy’s In the Company of Angels), is the Finnish composer Rautavara, for his “Angels and Visitations,” along with Stan Getz, whose “Blood Count” by Billy Strayhorn was recorded while Getz was already dying. Chet Baker, Dizzy Gillespie, John Coltrane, and Miles Davis are also featured. Eventually, Kerrigan decides to go to Dublin to share the atmosphere which James Joyce celebrated in Ulysses, before returning to Copenhagen.

Complex and dense, the novel challenges the reader to understand the reality of Copenhagen within the “verisimilitude” of the plot and the character of Kerrigan, whose attitudes, knowledge, and psychological attributes are developed here, along with his literary, artistic, musical, and historical background and knowledge. Eventually, Terrence Einhorn Kerrigan, whose initials are the same as those of Thomas E. Kennedy, stands before the reader and the Associate, ready to admit, with Matthew Arnold, that

McKluud's, a "western" bar, where Kerrigan has the second of his life-changing experiences in the conclusion of the novel. Double-click for more information. Photo by Scott Wood

“…the world, which seems

To lie before us like a land of dreams,

So various so beautiful, so new,

Hath really neither joy, nor love, nor light

Nor certitude, nor peace, nor help for pain;

And here we are as on a darkling plain…”

Then, again, we see him thinking for the first time, that even a darkling plain eventually has a dawn.

ALSO by Thomas E. Kennedy: IN THE COMPANY OF ANGELS, FALLING SIDEWAYS, BENEATH THE NEON EGG

Photos, in order: The author’s photo, by Laurie Hertzel, appears on http://www.startribune.com/

The Palace Theater was painted by Poul Gernes, who was famous also for overturning the idea that hospital rooms for sick children had to be white. He used a rainbow of colors there instead. http://www.bikereader.com

The statue of Bishop Absolom, photo by Willem Nabuurs, may be found on http://www.panoramio.com/

Hans Christian Andersen used Louise Collin as the model for both the haughty princess in his story of “The Swineherd” and as the prince in the “The Little Mermaid.” He saw himself as akin to the “Little Mermaid,” leading Kerrigan to observe that “[t is] hard to picture that lovely little bronze lady on her rock in the water of Langelinje as a transvestite. Andersen in scaly drag.”

http://www.tripadvisor.com.au/

Poet Patrick Kavanagh of Dublin (1904 – 1967), is second only to William Butler Yeats in popularity. As recently as 2000, ten of the “most popular poems in Ireland” were written by Kavanagh. Photo from http://www.irelandcalling.ie

McKluud’s, a “western bar” in Copenhagen, is where Kerrigan has his second life-changing moment at the conclusion. The photo by Scott Wood appears on http://www.travelistic.co.uk (Posted with permission from Scott Wood)

ARC: Bloomsbury