Note: Brazilian writer Clarice Lispector has been compared by Edmund White to both Franz Kafka and James Joyce.

“She was incompetent. Incompetent for life. She had never figured out how to figure things out. She was only vaguely beginning to know the kind of absence she had of herself inside her…So much that she had nothing to say for herself when the boss…rudely warned her that he was only going to keep Gloria, her co-worker, because as for her, she made too many typing mistakes, besides invariably dirtying the pages.”

In her final novel, Brazilian novelist/poet Clarice Lispector (1920 – 1977) writes an eerie, almost supernatural tale of Macabea, a nineteen-year-old woman almost totally devoid of personality, opinion, thoughts, and even feelings. Her story is being told by Roderigo S.M., a writer, similarly isolated, without a long-term idea of what he wants to write, though he says, as he begins the story, that he has “glimpsed in the air the feeling of perdition on the face of a northeastern girl [Macabea].” He tells the reader that his story, whatever it will be, will be both exterior and explicit in style but will contain secrets. He will have no pity, and he wants the story to be cold. “This isn’t just narrative, it’s above all primary life that breathes, breathes, breathes,” he states, leaving the reader in somewhat of a quandary trying to figure out what he is talking about.

In her final novel, Brazilian novelist/poet Clarice Lispector (1920 – 1977) writes an eerie, almost supernatural tale of Macabea, a nineteen-year-old woman almost totally devoid of personality, opinion, thoughts, and even feelings. Her story is being told by Roderigo S.M., a writer, similarly isolated, without a long-term idea of what he wants to write, though he says, as he begins the story, that he has “glimpsed in the air the feeling of perdition on the face of a northeastern girl [Macabea].” He tells the reader that his story, whatever it will be, will be both exterior and explicit in style but will contain secrets. He will have no pity, and he wants the story to be cold. “This isn’t just narrative, it’s above all primary life that breathes, breathes, breathes,” he states, leaving the reader in somewhat of a quandary trying to figure out what he is talking about.

In telling Macabea’s story, however, the narrator discovers that he himself has a kind of destiny, and that “the action of this story will end up with my transfiguration into somebody else and my materialization finally as an object. Yes, and it might even reach the sweet flute around which I will entwine myself like a supple liana.” Initially, though, the novel recreates the narrator’s maunderings as he tries to get started and wonders what to say. “Will things happen? They will. But what things? I don’t know that either.” He  recognizes the importance of keeping things simple in writing, though “I know splendid adjectives, meaty nouns, and verbs so slender that travel sharp through the air…I’m not going to adorn the word because if I touch the girl’s bread, the bread will turn to gold – and the girl…wouldn’t be able to bite it, dying of hunger.” She lives aimlessly, he says, and that “if she was dumb enough to ask herself ‘who am I?’ she would fall flat on her face…[She is] so dumb that she sometimes smiles at other people on the street. Nobody smiles back because they don’t even see her.”

recognizes the importance of keeping things simple in writing, though “I know splendid adjectives, meaty nouns, and verbs so slender that travel sharp through the air…I’m not going to adorn the word because if I touch the girl’s bread, the bread will turn to gold – and the girl…wouldn’t be able to bite it, dying of hunger.” She lives aimlessly, he says, and that “if she was dumb enough to ask herself ‘who am I?’ she would fall flat on her face…[She is] so dumb that she sometimes smiles at other people on the street. Nobody smiles back because they don’t even see her.”

Having grown up in the northeast of Brazil, Macabea, a child with rickets and no parents, moves first to Maceis with her “sanctimonious aunt,” who raps her on the head, beats her, and more importantly (to her), sometimes deprives her of daily dessert, “guava preserve with cheese, the only passion in her life.” As a result of this “upbringing,” Macabea develops into a person so unthinking that she “didn’t wonder why she was always being punished but you don’t have to know everything and not knowing was an important part of life.” She never worries about her ignorance because she does not recognize it. The only thing she does “know” for certain is that at the hour of death, a person “becomes a shining movie star, it’s everyone’s moment of glory, and it’s when as in choral chanting you hear the whooshing shrieks.”

When Macabea arrives in Rio, where she lives with several other girls, the narrator is not worried that she will become a prostitute. She “scarcely has a body to sell, nobody wants her, she’s a virgin and harmless, nobody would miss her. Moreover – I realize now – nobody would miss me either.” Macabea, a terrible typist, with only three years of school plus a crash course in typing, has few prospects in life but she never contemplates her future or thinks much about it at all. “Did she feel she was living for nothing? I’m not sure, but I don’t think so,” the narrator muses.

When Macabea arrives in Rio, where she lives with several other girls, the narrator is not worried that she will become a prostitute. She “scarcely has a body to sell, nobody wants her, she’s a virgin and harmless, nobody would miss her. Moreover – I realize now – nobody would miss me either.” Macabea, a terrible typist, with only three years of school plus a crash course in typing, has few prospects in life but she never contemplates her future or thinks much about it at all. “Did she feel she was living for nothing? I’m not sure, but I don’t think so,” the narrator muses.

On the morning of May seventh, however, “the unexpected ecstasy for her tiny little body [arrives]. The open and glittering light of the streets went right through her opacity. May, the month of bridal veils floating in white.” She meets a boyfriend, a man as ignorant as she is, also from the backlands of Paraiba. They don’t know how to take a walk or converse, and long silences punctuate their time together, with Macabea “conversing” with such statements as “I just love bolts and nails, what about you, sir?” His name is Olimpico de Jesus Moreira Chaves, a worker in a metals factory, and just as she calls herself a typist to give meaning to her life, he calls himself a metallurgist and believes himself to be so intelligent he could become a congressman. Still, they “cast little shadow upon the ground.”

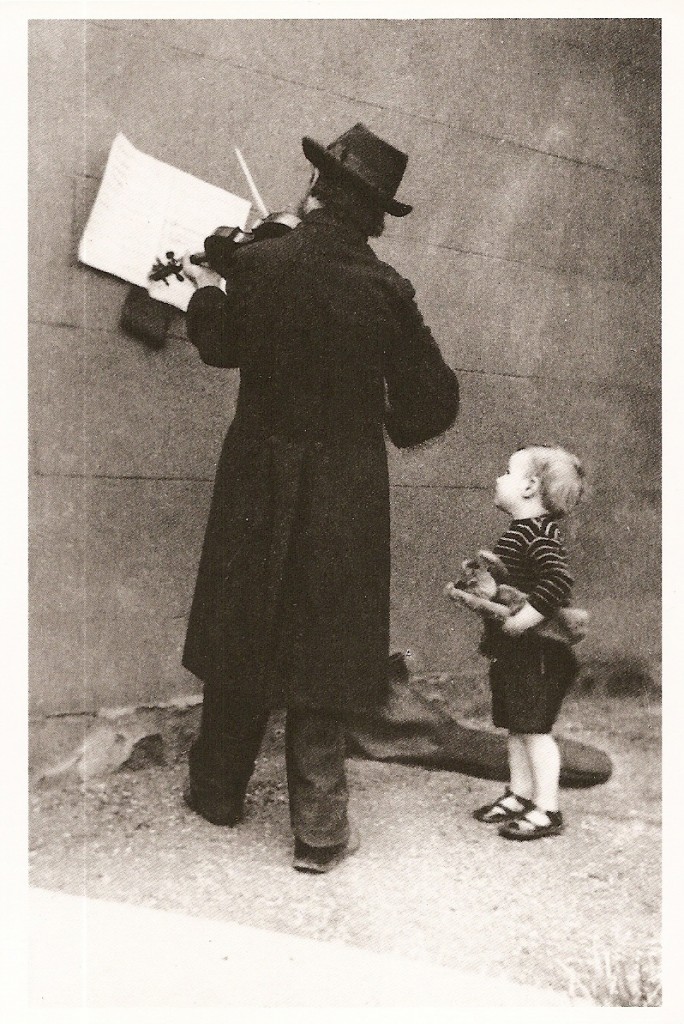

When the narrator was a small boy, he saw a violinist playing alone at night. At the conclusion of the novel, he finally realizes its symbolism for his life.

Several pages of their conversations are among the most amazing writing imaginable – neither Macabea nor Olimpico has a clue about anything and as they try to find some level of interest in something – anything! – which will allow them to talk, the results are both hilarious and pathetic. The narrator himself gets discouraged with his subject, takes some time off, then returns to the romance, admitting that he himself is in love with “her ugliness and total anonymity since she belongs to no one.” He longs to have her open her mouth and say “I am alone in the world and I don’t believe in anyone, everyone lies…I don’t think one being speaks to another, the truth only comes to me when I’m alone.” But Macabea is too much a prisoner of her ignorance even to think these sentiments.

A trip to a fortune teller and its aftermath provide the turning point of the novel. Irony builds upon irony as the author explores who we are, how we know, how we fit into the grand scheme of life, and ultimately, whether there actually is any “grand scheme.” In this odd but peculiarly thought-provoking novel, the reader will often be as confused and conflicted as the narrator, but the book may be unique in its subject matter and approach to writing, and after a slow start, I became enchanted with it. Here two complete negatives, Macabea and author Roderigo, have created a bizarre positive. Ultimately, Roderigo asks, “What was the truth of my Maca? As soon as you discover the truth it’s already gone: the moment passed, I ask: What is? Reply: it’s not.”

Photos, in order: The author’s photo appears on http://www.listal.com

Maceio, where Macabea’s aunt lived with her, is seen on http://mccammon.ucsd.edu

When the narrator was a small boy, he saw a violinist playing alone at night. At the conclusion of the novel, he finally realizes its symbolism for his life. http://dustykate.blogspot.com