“This is a story that can only be told in a whisper. There is a hush to difficult forms of knowing, an abashment, a sorrow, an inclination towards silence. My throat is misshapen with all it now carries. My heart is a sour, indolent fruit. I think the muzzle of time has made me thus, has deformed my mouth.”

Australian author Gail Jones, who has won major recognition and prizes in Australia for every book she has written over the past twenty years, achieved another notable milestone with Sorry, which was shortlisted for no fewer than six major prizes in the UK and Australia in 2008. Set in remote and sparsely populated Western Australia in the early 1940s, the novel recreates the life of Perdita Keene, a ten-year-old child not wanted by her British expatriate parents, who had hoped she would die at birth. Perdita, whose childhood is formed by the aborigine women who nursed her in infancy, develops a strong friendship with Mary, an aborigine girl five years older, and Billy, the deaf-mute son of the Trevors, white people who run a local cattle station. All three children are outcasts for various reasons, and their bonds with each other are total and life-affirming.

Australian author Gail Jones, who has won major recognition and prizes in Australia for every book she has written over the past twenty years, achieved another notable milestone with Sorry, which was shortlisted for no fewer than six major prizes in the UK and Australia in 2008. Set in remote and sparsely populated Western Australia in the early 1940s, the novel recreates the life of Perdita Keene, a ten-year-old child not wanted by her British expatriate parents, who had hoped she would die at birth. Perdita, whose childhood is formed by the aborigine women who nursed her in infancy, develops a strong friendship with Mary, an aborigine girl five years older, and Billy, the deaf-mute son of the Trevors, white people who run a local cattle station. All three children are outcasts for various reasons, and their bonds with each other are total and life-affirming.

The murder of Perdita’s father, described in the opening pages, is at the core of the novel, and the circumstances surrounding the case are not clear. All three children witness the crime, but Perdita, the narrator for most of the novel, is so traumatized that she cannot remember any of the details except a blood-spattered blue dress, made from a fabric used to make several dresses for several different wearers.

If there is such a genre as “Australian Gothic,” this novel would be one of its best-written examples. The sights, sounds, and smells of the bush, filled with storms, heat, dust, and exotic birds and animals, vibrate with life—and death—both physical and spiritual. Perdita’s father, as the reader comes to know him, has long lost his academic interest in research on aborigine myths and leads a mean-spirited and abusive life. He compulsively maps the progress of World War II battles, posting photographs of gory battle scenes, which he cuts from the newspaper. He has little time or emotion left over for his wife or child. Perdita’s mother, who seeks life lessons and values in the plays and sonnets of Shakespeare, which she has memorized almost in their entirety, is hospitalized periodically because she loses touch with reality. She scorns her husband, hates motherhood, and despises her life in their tiny, shack, crowded with pillars of books and papers, and invaded by mice and snakes.

Perdita, “the lost one,” appropriately named for a character in Shakespeare’s The Tempest, finds a sense of self with the aborigines, who value the continuum of life, not merely a set of static principles, like the whites who have driven them from their ancestral lands and forcibly removed their children. Aborigine children, warehoused in dormitories and schooled to remove all traces of their own culture, learn trades so that they can wait on those “civilized” inhabitants who have taken their lands. Perdita is, on some level, aware of the injustices, having observed the rape of young aborigine girls (which she does not comprehend), and she finds solace and a sense of order in aborigine culture which she does not see in her own. She understands and loves the sense of kinship and sharing which govern their lives, as opposed to the cult of the individual which she sees in her own society.

Perdita, “the lost one,” appropriately named for a character in Shakespeare’s The Tempest, finds a sense of self with the aborigines, who value the continuum of life, not merely a set of static principles, like the whites who have driven them from their ancestral lands and forcibly removed their children. Aborigine children, warehoused in dormitories and schooled to remove all traces of their own culture, learn trades so that they can wait on those “civilized” inhabitants who have taken their lands. Perdita is, on some level, aware of the injustices, having observed the rape of young aborigine girls (which she does not comprehend), and she finds solace and a sense of order in aborigine culture which she does not see in her own. She understands and loves the sense of kinship and sharing which govern their lives, as opposed to the cult of the individual which she sees in her own society.

As Jones develops her story, she uses the battles of World War II, studied by Perdita’s father, to parallel Perdita’s own troubles and to illuminate the contrasts within Perdita’s life, emphasizing the novel’s major themes of war and peace, oppression and liberation, and order and chaos, both in society and within the individual. Entitled “Sorry” to honor the abused aborigine population, Jones notes that the long-time federal policy of “removing” children continued until 1977, and that as recently as 1997, Prime Minister John Howard refused to acknowledge that the nation was “sorry” for its injustices against the aborigines, despite the national desire for reconciliation. Because of John Howard’s refusal to apologize, a group of citizens established their own “National Sorry Day” in 1998, and initiated attempts at reconciliation with the indigenous community. National Sorry Day has continued to the present, now as a National Holiday.

Jones’s novel is not a political screed, nor is it a story about a national shame, except peripherally. It is a story about a child, Perdita, who finds herself caught between two worlds—and learns the worst and the best about both. Lyrical, sensual, and full of passion, Sorry is a novel that makes no apologies for its emotion or its dramatic intensity. For the author, they are all part of being “sorry.”

ALSO by Gail Jones: FIVE BELLS

Photos, in order: The author’s photo appears on http://www.mwf.com.au

A picture from 1950 of aborigine children at the schools to which the government sent them unwillingly appears on http://www.hreoc.gov.au

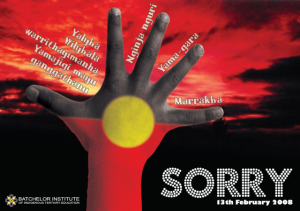

The Aborigine flag is one of several “official flags” of Australia, though it is not the Australian National Flag. It was designed by Aboriginal artist Harold Thomas: http://en.wikipedia.org

The poster designed for National Sorry Day in 2008, uses elements from the Aborigine flag in its design. The holiday is now celebrated each year on May 26. http://batchelorpress.com