Note: This book was WINNER of the Governor General’s Award for Non-fiction in Canada, 2012.

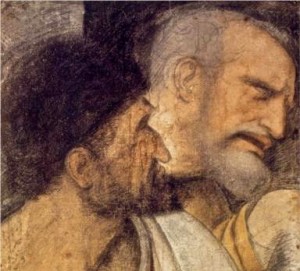

“[In the Last Supper] Leonardo outlined the distinctive reactions of the participants in terms of both their physical actions (lifting or upsetting a glass, holding a knife, recoiling backward, or leaning forward) and their facial expressions (furrowed brows, shaded eyes, and the bocca della maraviglia, or mouth of astonishment). He froze the moment in time so the spectator would see the dinner guests in mid-gesture, with the loaf of bread ‘half cut through’ and the drinking glass still at the lips.”

With unusual insight and great enthusiasm, Ross King has several times written books about monumental works of art, placing them in historical context, characterizing the artist, and emphasizing what makes these artistic achievements unique. Each of these books about an artwork – the dome of a cathedral, the Sistine Chapel ceiling, and the Last Supper mural – has received international recognition for its literary style, the accuracy of the research, and the excitement King generates as he details the trials and troubles the artist faces while creating his work for a sometimes less-than-adoring public. Brunelleschi’s Dome: How a Renaissance Genius Reinvented Architecture was Non-Fiction Book of the Year for Book Sense in 2000. Michelangelo and the Pope’s Ceiling was nominated for both the 2003 National Book Critics Circle Award and the Governor General’s Literary Award (Canada), and this year Leonardo and the Last Supper was winner of the Governor General’s Award for Non-Fiction – all well deserved prizes. King’s fast-paced narrative style, his vibrant descriptions (aided by well chosen illustrations), and intuitive understanding of what makes art come alive for readers make him unique among contemporary authors, a man whose writing about an artwork pays true homage to the art itself.

With unusual insight and great enthusiasm, Ross King has several times written books about monumental works of art, placing them in historical context, characterizing the artist, and emphasizing what makes these artistic achievements unique. Each of these books about an artwork – the dome of a cathedral, the Sistine Chapel ceiling, and the Last Supper mural – has received international recognition for its literary style, the accuracy of the research, and the excitement King generates as he details the trials and troubles the artist faces while creating his work for a sometimes less-than-adoring public. Brunelleschi’s Dome: How a Renaissance Genius Reinvented Architecture was Non-Fiction Book of the Year for Book Sense in 2000. Michelangelo and the Pope’s Ceiling was nominated for both the 2003 National Book Critics Circle Award and the Governor General’s Literary Award (Canada), and this year Leonardo and the Last Supper was winner of the Governor General’s Award for Non-Fiction – all well deserved prizes. King’s fast-paced narrative style, his vibrant descriptions (aided by well chosen illustrations), and intuitive understanding of what makes art come alive for readers make him unique among contemporary authors, a man whose writing about an artwork pays true homage to the art itself.

Leonardo and the Last Supper begins in the chaotic year of 1494, when Leonardo da Vinci and his patron Lodovico Sforza, the ruler of Milan, are both forty-two. The author then establishes Leonardo’s character through flashbacks – his early youth in Florence, his family life, and his apprenticeship with Verocchio, with whom he worked for about seven years. Though he had more raw talent than almost anyone else in Europe, Leonardo was a frustration to his patrons, however. “His career in both Florence and [later] Milan, had seen several major commissions abandoned and unfinished…Few completed works could be attached to [his] name, beyond an Annunciation altarpiece [ from 1481] in a convent outside Florence, several Madonna and child paintings done for private patrons, and a number of portraits…tucked away in private homes, unseen by anyone but princes and courtiers.”

Study for equestrian statue of Francesco Sforza

In 1482, after working for Lorenzo de Medici for several years, Leonardo was sent from Florence to Milan bearing a silver lyre in the shape of a horse’s head, a gift he had made for Lorenzo, who hoped to use it to secure peace with Lodovico Sforza, ruler of Milan. Leonardo remained in Milan with Lodovico as his patron for the next sixteen years, hoping for work as an engineer but, once again, getting commissions almost exclusively for his painting – work which, once again, he often did not finish. The famous “Virgin of the Rocks,” begun in 1483 as an altarpiece for a chapel, was unfinished, in part because Leonardo failed to paint it according to the description given in his contract. In 1484, Lodovico contracted with him to create a monumental bronze equestrian statue honoring Francesco Sforza, his father. Leonardo intended to make it twenty-three feet high, three times the natural size, and in an unusual position requiring complex engineering skills for its balance. That, too, was long delayed, with a full-sized clay model not made until nine years later, in 1493. Leonardo lost the seventy-five tons of bronze he had hoped to use to cast the statue, however, when the French, under King Charles VIII invaded Italy in 1494, and the bronze was needed for the war to come. Another unfinished project.

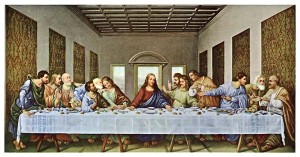

In 1494, he also received the contract to paint the Last Supper on the refectory wall of a Dominican convent, Santa Maria delle Grazie, a large space measuring fifteen feet by twenty-nine feet. Leonardo had never had any experience with fresco, which requires paint to be applied to wet plaster. In addition, fresco must be painted quickly, with no opportunity for corrections once the plaster dries, and that was inimical to Leonardo’s own careful style. He decided to create a whole new formula – an “oil tempera,” which could be painted on a dry wall and which allowed for corrections. Five layers of oil color, including vermillion and ultramarine, which were impossible to use with fresco, would allow him to create the most brilliantly colored mural ever.

In 1494, he also received the contract to paint the Last Supper on the refectory wall of a Dominican convent, Santa Maria delle Grazie, a large space measuring fifteen feet by twenty-nine feet. Leonardo had never had any experience with fresco, which requires paint to be applied to wet plaster. In addition, fresco must be painted quickly, with no opportunity for corrections once the plaster dries, and that was inimical to Leonardo’s own careful style. He decided to create a whole new formula – an “oil tempera,” which could be painted on a dry wall and which allowed for corrections. Five layers of oil color, including vermillion and ultramarine, which were impossible to use with fresco, would allow him to create the most brilliantly colored mural ever.

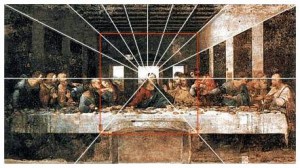

Study of the perspective of this painting, with the point just beside the head of Jesus on the left. The composition involving four groups of three disciples is obvious here. Note that a a door has now been cut into the wall, eliminating forever the feet of Jesus and those of the disciples nearest to him.

The thirteen figures in the painting involved complex composition and careful research into the nature of the characters, but Leonardo studied the Gospels, especially that of John, for information on the actual supper, which both John and Matthew had witnessed. He wanted to know more about the events involving Judas and whether he was paid to betray Jesus, and also whether this was a regular dinner or a communion service created from the food and drink. His realistically depicted supper shows a salt cellar overturned, not a wine glass, a loaf of bread sliced half through, and a meal of oranges and eels on the table. His characters, often seen in three-quarter view, look and act like real people, and since the Dominicans were experts on the hand gestures so common to Italians as they speak and listen, Leonardo also studied hands as an additional way of communicating the attitudes of the disciples.

Head of Judas (left), looking past Peter (right)

The work was finished between summer 1497 and spring 1498, and people were astounded by its color and power. Unlike fresco, however, it began to deteriorate within twenty years, and it has been subjected, over the past five hundred years, to atrocious attempts to restore it by scraping, bleaching, and over-painting it. The most recent restoration, lasting from 1977 – 1999, has left the mural as close to the original as is possible, but with only twenty percent of the original painting intact, eighty percent of it now added by restorers.

Ross King’s book contains far more information than one can discuss here about Leonardo and his personal life, his commissions, his work in many fields, and the complex political rivalries of the period involving Girolamo Savonarola in Florence, King Charles VIII of France, King Alfonso II of Naples, and Lodovico Sforza of Milan, and this research adds context to Leonardo’s work and may explain some of his difficulties as an artist. Art historian and critic Bernard Berenson sums up Leonardo this way: “Leonardo is the one artist about whom it may be said with perfect literalness: Nothing that he touched but turned into a thing of eternal beauty.” Ross King honors that assessment with this book.

ALSO by Ross King: MICHELANGELO AND THE POPE’S CEILING, BRUNELLESCHI’S DOME: How a Renaissance Genius Reinvented Architecture, MAD ENCHANTMENT: Claude Monet and the Painting of the Water Lilies

Photos, in order: The author’s photo appears on http://bookpassage.com

The drawing of the equestrian statue may be found on http://100swallows.wordpress.com

This copy of the Last Supper is from http://godwords.org

The study of perspective appears on http://www.paintdrawer.co.uk

The close-up of Judas and Peter may be found on http://zondervan.typepad.com