“How alike are the voices of [carnal] pleasure and death! When one is summoned, all work at once becomes unimportant. As on a ghost ship abandoned by its crew, be it the entries in the log, the uneaten food, the half-polished shoes, the comb left before the mirror, or even the partially knotted ropes – everything breathes of the mysteriously departed men, everything is left as it was in the haste of departure.”—Shigekuni Honda, 1952.

Shigekuni Honda, the main character in this third novel of the Sea of Fertility tetralogy by Yukio Mishima, is forty-six years old in 1940, as the novel opens. He has matured into a successful lawyer and judge in the years since 1912 – 1914, when he was first introduced as the schoolboy friend of Kiyoake Matsugae, the son of a samurai family. Kiyoake, however, died at a young age in Spring Snow, and his death has haunted Honda for the rest of his life. Runaway Horses, the second novel of the tetralogy, takes place during the economic crisis in Japan of 1932 – 1933. In this novel, Honda sees Isao Iinuma, the nineteen-year-old son of Kiyoaki’s former tutor, as the physical reincarnation of Kiyoaki. Through his total dedication to the traditional, conservative goals of the samurai, a goal which author Yukio Mishima also shared, Isao hoped to eliminate all traces of foreign influence from Japan. His horrifying death, however, added to the trauma of loss for Honda. He was convinced that Kiyoaki “perished on the battlefield of romantic emotions” but that Isao was the first of many young men who faced death on real battlefields. “Kiyoaki and his reincarnation, Isao, had died contrasting deaths on contrasting battlefields,” the author concludes.

Shigekuni Honda, the main character in this third novel of the Sea of Fertility tetralogy by Yukio Mishima, is forty-six years old in 1940, as the novel opens. He has matured into a successful lawyer and judge in the years since 1912 – 1914, when he was first introduced as the schoolboy friend of Kiyoake Matsugae, the son of a samurai family. Kiyoake, however, died at a young age in Spring Snow, and his death has haunted Honda for the rest of his life. Runaway Horses, the second novel of the tetralogy, takes place during the economic crisis in Japan of 1932 – 1933. In this novel, Honda sees Isao Iinuma, the nineteen-year-old son of Kiyoaki’s former tutor, as the physical reincarnation of Kiyoaki. Through his total dedication to the traditional, conservative goals of the samurai, a goal which author Yukio Mishima also shared, Isao hoped to eliminate all traces of foreign influence from Japan. His horrifying death, however, added to the trauma of loss for Honda. He was convinced that Kiyoaki “perished on the battlefield of romantic emotions” but that Isao was the first of many young men who faced death on real battlefields. “Kiyoaki and his reincarnation, Isao, had died contrasting deaths on contrasting battlefields,” the author concludes.

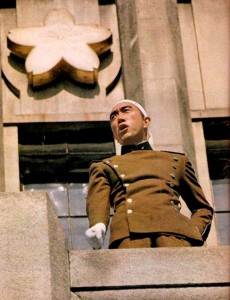

Yukio Mishima rallies the crowd in a failed coup attempt just prior to committing seppuku (November 25, 1970)

The Temple of Dawn takes place in the years immediately preceding World War II, just after the “China Incident” of 1936, and Honda, having abandoned his formerly altruistic ideals, is still trying to develop his own beliefs about life, death, love, the transmigration of souls, and reincarnation. War is imminent now, as Japan, Germany, and Italy have signed a treaty against the Americans. Having given up his judgeship, Honda lives in partial retirement, but he takes a business trip to Bangkok, where he also hopes to meet Prince Pattanadid and Prince Krisada, former school friends from his youth. The Thai royal family has gone to Switzerland, however, and the palace is empty. The only person there is a “mad princess,” age seven, who lives as a virtual prisoner, claiming publicly that “I’m not really a Siamese princess. I’m the reincarnation of a Japanese, and my real home is in Japan.” Having been exposed to the idea of samsara, Honda eventually becomes certain that this little princess, “Princess Moonlight,” is the reincarnation of Kiyoake/Isao.

Serious discussions of Buddhism pervade the beginning of the novel, with Mishima giving great detail about Thai Theravada Buddhism and its practices as he departs Thailand for a trip to Calcutta, Benares, and the Ajanta caves in India. In Calcutta, he studies Kali worship and visits the Kalighat, observing the sacrifice of goats and the display of their heads around a fireplace burning in the rain. In Benares he is impressed by the “extreme filth as well as the extreme holiness,” especially along the Ganges, and he notices the sexual paintings that exist in juxtaposition with the House of Widows awaiting their own deaths. A multitude of ghats, all cremating remains in the open air in a “purification of the human body, returning its parts to its four elemental constituents.” Honda notes that there is “no sadness. What seemed heartlessness was actually pure joy.” After exploring the land of the Hindus, Honda then decides to seek out “the ruins of Buddhism,” now extinct in India, by traveling to the Ajanta caves, northeast of Mumbai. The differences between Mahayana Buddhism and Theravada Buddhism, and Buddhism’s other permutations, occupy many pages in this section of the book, leading Honda to think more seriously about what is reality, what is death, what is love, and what happens after death? Does the world even exist? He begins to refine his ideas about reincarnation, samsara.

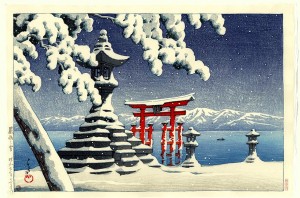

The red torii, which the author mentions, seen against the snowy backdrop of Mount Fuji, 1932. By Kawase Hasui (1883 – 1957)

Part II, taking place twelve years later, in 1952, opens on Honda’s fifty-seventh birthday. Honda has just won a huge case, one begun generations ago in the late nineteenth century, but which continued up to the present, involving the redistribution of land. As a result, he now has a large lot and house facing the magnificence of Mount Fuji. Totally retired, and living more or less companionably with his wife Rie, Honda is still pursuing his philosophical inquiries. The relationships between love, sex, and death now receive a longer analysis as Honda becomes infatuated with a seventeen-year-old female whom he now believes is the next incarnation of Kiyoaki and Isao. Princess Chantrapa II, known as Ying Chan or Princess Moonlight, the formerly mad princess he met in Bangkok when she was seven, is now seventeen, and she is studying in Japan.

He plans to invite her to the birthday party at his house, where he will give her an important present. Years ago, he had located a large emerald ring at the shop of a Thai prince, and he recognized it immediately as the ring which another Thai Prince, Chao Pattanadid, his schoolmate, had intended to give to the woman he loved, Princess Chantrapa. The ring had been stolen from their school, and Honda, after finding it, years later, in a shop belonging to another prince, had bought it but had not yet had a way to return it. This section of the novel brings the philosophical ideas here to a head, and concludes the narrative in dramatic fashion.

Imperial Hotel, designed by Frank Lloyd Wright, destroyed in 1967. The facade has been preserved in the Meiji Mura Museum.

Set as it is in the period before and after World War II, but completely skipping over the war itself, the novel has more philosophical analysis and detail than it does narrative action, and some readers who have enjoyed Spring Snow and Runaway Horses may weary of the deep discussion of the varieties of Buddhism, and the ideas of death and reincarnation which Honda traces through numerous religions and Asian cultures. Mishima himself is clearly using the novel to try to work out his own ideals and provide a forum for discussion in the aftermath of Japan’s war-time defeat. A total believer in the old samurai traditions, he despaired of the western influence he saw appearing in post-war Japan, and he never forgave the emperor for denying his divinity in the capitulation which ended the war. Just after author Yukio Mishima finished the final novel in this “Sea of Fertility” tetralogy, the Decay of the Angel on November 25, 1970, he disemboweled himself in a ritual suicide—seppuku—committed in the presence of four members of his private army. He was then beheaded, in accordance with ritual.

ALSO by Mishima: THE FROLIC OF THE BEASTS, SPRING SNOW(#1), RUNAWAY HORSES(#2), STAR, LIFE FOR SALE

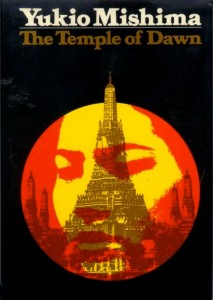

Photos, in order: The author photo of Yukio Mishima delivering his speech in a failed coup attempt, just prior to committing seppuku (November 25, 1970), is from http://www.jack-donovan.com/mishima/

Cave #19, from Ajanta, ca. 460 – 480, is by Marcin Bialek: http://commons.wikimedia.org

The red torii, mentioned in the novel, are shown here in a 1932 print by Kawase Hasui (1883 – 1957),http://www.fujiarts.com/japanese-prints

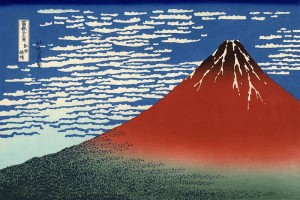

The Fuji Sunset, from the 36 Views of Mount Fuji, by Hokkusai, appear on http://wellfrog.exblog.jp/

The facade of Tokyo’s Imperial Hotel, by Frank Lloyd Wright, demolished in 1967, has been preserved in the Meiji Mura Museum. http://www.incredibleart.org

The panorama of the Ajanta Caves is from http://en.wikipedia.org/