Note: This novel was WINNER of the Premio Herralde de Novela for Best Debut Novel in Spain when it was first published in 1999.

“We live our lives thinking we know who we are and how we’ll react in any given situation, but we just have to dig around a little in our memories to find significant examples of when we reacted quite differently from how we should have reacted…The variables that govern our responses, like the variables of memory, are entirely unforeseeable…Even our reactions or responses to the same stimulus are not always the same.”

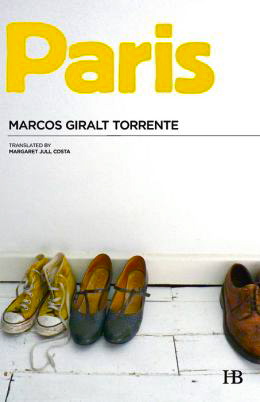

Published in Spain in 1999 and just translated into English for the first time by renowned translator Margaret Jull Costa, Paris plumbs the depths of emotions, memories, and thoughts of the main character – as a schoolboy at the beginning and as an adult in the conclusion, twenty-two years later – as he tries to understand and reconcile serious issues about his father and mother, nearly all of which his mother keeps secret from him. The boy and his mother share an intensely interdependent life since his father is absent for most of the novel, and though the boy accepts the little his mother does say about his father, he also explores on his own and discovers nuggets of additional information about his father which make him question everything else he already “knows.” When, later in the novel, circumstances arise which his mother could never have predicted, he begins to question her whole story and all its mysteries: “When our knowledge of a subject depends on the words of others, we can never be sure if they’ve told us everything or only a part….One often lies to and deceives the person one loves most in order to preserve their love, or to protect them.” He wonders “how much my mother will keep silent about until the end of her days.”

Published in Spain in 1999 and just translated into English for the first time by renowned translator Margaret Jull Costa, Paris plumbs the depths of emotions, memories, and thoughts of the main character – as a schoolboy at the beginning and as an adult in the conclusion, twenty-two years later – as he tries to understand and reconcile serious issues about his father and mother, nearly all of which his mother keeps secret from him. The boy and his mother share an intensely interdependent life since his father is absent for most of the novel, and though the boy accepts the little his mother does say about his father, he also explores on his own and discovers nuggets of additional information about his father which make him question everything else he already “knows.” When, later in the novel, circumstances arise which his mother could never have predicted, he begins to question her whole story and all its mysteries: “When our knowledge of a subject depends on the words of others, we can never be sure if they’ve told us everything or only a part….One often lies to and deceives the person one loves most in order to preserve their love, or to protect them.” He wonders “how much my mother will keep silent about until the end of her days.”

As he thinks about telling his own story, he believes that “there will be nothing contradictory…as long as everything I say is told from my point of view at the time. Any gaps other than those in my own memory will have to continue to exist, because…what purpose would there be in trying to investigate them further?” Foreboding looms over every page, and Giralt Torrente does a remarkable job of tantalizing the reader with tiny bits of new information, as the boy accumulates it over the years, but even as an adult, with his mother in a nursing home, the boy, now man, occasionally has nightmares related to these childhood years. He lives in a permanent state of incomplete knowledge about his childhood, and he is unhappy that “I will never know more than I know now.” Perhaps, he suggests, “it’s the impossibility of getting beyond mere speculation,” the perpetual uncertainty about his past, that is so difficult to cope with.

Burgos, where the boy's father was in prison, is also, ironically, the birthplace of Spain's national hero, El Cid.

As the novel begins, the young boy describes his father’s arrest one night when the family has guests for dinner, followed by his father’s subsequent disappearance for two years. The boy is young enough that his father’s disappearance to some unknown place is something he simply accepts. It is not until later that the boy learns about a suitcase of money that his father had hidden under the bed. Gradually, he also learns of other mysterious schemes in which his father has been involved, just as he has also been involved with several other women. One of his most vivid memories occurs two years after his father’s arrest, when his mother tells him that they are going to Burgos to pick up his father, reminding him in the car on the way that anyone can make a mistake, while she also “paints a picture of him that [is] real and at the same time comprehensible and forgivable.” After his father’s release from prison, his father spends little time at home, and he receives strange phone calls. He does not seem to have regular work. On one family trip to Toledo to “see an exhibition” at the castle, which is closed for the day, the family stops at a bar for something to eat. A strange man comes up to talk at length with the “Professor,” his father, in a vernacular that the boy has never heard before, something he later learns is “prison slang.” His mother tells him nothing more, though the boy prowls around when no one is at home and discovers a few secrets in his father’s “office.”

When the father disappears again later, the boy goes with his mother to visit her sister in La Coruna, a seaside community many hours’ drive from Madrid, where he has often spent the summer. This time, however, he learns that he will be staying there with his childless aunt Delfina for most of a year, even going to school there, while his mother travels mysteriously to Paris to live. Bereft of both parents, the resilient boy still copes, but he has no idea what his mother is doing in Paris and is not able to visit her there while she is gone. Upon her return almost a year later, the boy has grown older and developed feelings of adolescent rebellion, sometimes getting angry with her now. “My mother had not been the same since she returned from Paris,” he tells us, “and although it’s true that I could not have said what the difference was, I was sure she had undergone some kind of transformation.” The mystery of Paris becomes and remains a major question about his mother’s life.

When the boy and his family are in Toledo they go to a bar/cafe, where the father is recognized as the "Professor," and has a conversation in "prison slang" with a former inmate.

Students of writing will be fascinated by the ways in which Giralt Torrente maintains suspense by presenting information in little dribbles instead of in big, dramatic scenes. He has a formidable task, since the “action” of the novel takes place almost exclusively inside the boy’s head – his inner thoughts, the assumptions he makes about his mother, the conclusions he draws about his father, questions he has which never get answered, and the lack of any kind of finality or reconciliation about the questions surrounding his family and his own life. The second big challenge which Giralt Torrente faces also grows out of all this internal action. Because nothing much really happens externally in terms of dramatic scenes, there is very little dialogue, other than what the main character has with himself. This eliminates much of the subtle interaction among characters which readers customarily use to identify with characters and draw conclusions about who they “really” are. Instead, the author tells us in great detail what the main character is thinking and feeling, filtering information about others and their relationships through the boy’s reactions and not through the objective lens of the characters’ own interactions.

Waterfront sculpture/mosaic in La Coruna, where the boy lived for almost a year with his aunt while his mother was in Paris.

Though some of the mysteries of the novel remain mysteries even in the conclusion, there is one dramatic revelation (so tucked away that anyone who skims the final pages will miss it) that constitutes a complete paradigm shift, one which changes every aspect of the main character’s life and all the reader’s perceptions. Now, twenty-two years after the opening scenes, the reader must ponder this shocking new information and view it and the past in light of the main character’s earlier statement that “the lie intended to preserve love is the one you never reveal.”

Photos, in order: The author ‘s photo appears on http://ivanthays.com.pe

The Burgos monument to El Cid, Spain’s national hero from the 11th century, appears on http://en.wikipedia.org/ Photo by ElCaminodeSantiago09 2006 on Flicker, with many other photos from Burgos.

The Alcazar Castle in Toledo may be found on http://www.viator.com/ It was closed when the family arrived.

The family then went to a cafe/bar, with “a very cramped space, and at the back, a few tables topped with faux-wood Formica. ” They decided to sit instead at the bar. http://www.latortugaviajera.com

The octopus sculpture on the waterfront in La Coruna, where the boy lived for almost a year, is a well-known local landmark: http://davidsbeenhere.com

The prison at Burgos appears on http://www.panoramio.com Photo by mmrespeto on http://www.panoramio.com/, which also includes many other photos from Burgos.

ARC: Hispabooks

The isolated Burgos Prison is a far cry from the elegant setting of the statue of El Cid, the national hero of Spain from the 11th century, also in Burgos.