Note: Louise Erdrich was WINNER of the 2015 Library of Congress Prize for American Fiction, WINNER of the PEN/Saul BellowAward for Achievement in American Fiction, and WINNER of the National Book Award for Fiction for The Round House.

“Landreaux had kept track of the buck all summer, waiting to take it fat, until just after the corn was harvested….The buck had regular habits and had grown comfortable on its path…It would wait and watch through midafternoon….Landreaux was downwind [and] he [finally] took his shot with fluid confidence. When the buck popped away, he realized he’d hit something else – there had been a blur the moment he squeezed the trigger….”

Within the first two paragraphs of this dramatic and incisive study of human relationships, author Louise Erdrich, a member of the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa (Ojibwe) Indians, introduces a series of powerful conflicts which pit family against family, culture against culture, and generation against generation. In the opening scene, quoted at the top of the review, Landreaux Iron, a careful and respected member of his culture, accidentally kills Dusty Ravich, the five-year-old son of Peter Ravich, a friend and family member with whom he had planned to share the meat from the buck. Racing back to Peter’s house, Landreaux encounters Peter’s wife Nola, who becomes understandably hysterical, and by the time the tribal police, the county coroner, and the state coroner have arrived, the trauma has been felt by all the members of both devastated families.

Within the first two paragraphs of this dramatic and incisive study of human relationships, author Louise Erdrich, a member of the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa (Ojibwe) Indians, introduces a series of powerful conflicts which pit family against family, culture against culture, and generation against generation. In the opening scene, quoted at the top of the review, Landreaux Iron, a careful and respected member of his culture, accidentally kills Dusty Ravich, the five-year-old son of Peter Ravich, a friend and family member with whom he had planned to share the meat from the buck. Racing back to Peter’s house, Landreaux encounters Peter’s wife Nola, who becomes understandably hysterical, and by the time the tribal police, the county coroner, and the state coroner have arrived, the trauma has been felt by all the members of both devastated families.

A resident of Pluto, a town in the same North Dakota/Minnesota area that Erdrich has used many times as the settings for previous novels, Landreaux is a devout Catholic, and he immediately goes to talk with Father Travis about his guilt and heartbreak. Later, he, his wife Emmaline, and their five-year-old son LaRose take further solace in the traditions of their Indian culture by going to the sweat lodge. There, in their mystical dreams, they have a vision of the future. True justice and repentance, they decide, can only be achieved if Landreaux gives his own five-year-old son, LaRose, to Peter Ravich and his wife Nola to raise as their own. LaRose, a child who seems older than his years, has inherited a name which has been passed down through each generation of Landreaux’s family for over a hundred years, and each of the LaRoses, both male and female, has shown connections to the spirit world and insights into the most sacred aspects of Ojibwe culture. As he goes to live with the Raviches, LaRose desperately misses Emmaline, his mother, as any five-year-old would, but he also sees beyond himself and adapts to his new situation, accepting the statement Landreaux has made to Peter: “Our son will be your son now. It’s the old way.”

A resident of Pluto, a town in the same North Dakota/Minnesota area that Erdrich has used many times as the settings for previous novels, Landreaux is a devout Catholic, and he immediately goes to talk with Father Travis about his guilt and heartbreak. Later, he, his wife Emmaline, and their five-year-old son LaRose take further solace in the traditions of their Indian culture by going to the sweat lodge. There, in their mystical dreams, they have a vision of the future. True justice and repentance, they decide, can only be achieved if Landreaux gives his own five-year-old son, LaRose, to Peter Ravich and his wife Nola to raise as their own. LaRose, a child who seems older than his years, has inherited a name which has been passed down through each generation of Landreaux’s family for over a hundred years, and each of the LaRoses, both male and female, has shown connections to the spirit world and insights into the most sacred aspects of Ojibwe culture. As he goes to live with the Raviches, LaRose desperately misses Emmaline, his mother, as any five-year-old would, but he also sees beyond himself and adapts to his new situation, accepting the statement Landreaux has made to Peter: “Our son will be your son now. It’s the old way.”

As Wolfred Roberts and the first LaRose try to escape from Mackinnon, they emerge from the woods, at one point to “a hundred or more [bark houses] set up along the bends of a river,” an event which changed the lives of Wolfred and LaRose.

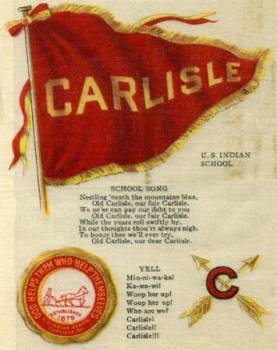

The banner, school song, and school yell for the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, which an early LaRose attended, changed her life by giving her skills that allowed her to survive in the outside world, while changing her view of herself. Double-click to enlarge.

These parallel stories of different generations continue to alternate throughout the novel as the children of Landreaux and Emmaline grow up beside the children of Peter and Nola Ravitch, with LaRose serving as a bridge between the two families. Erdrich makes her characters reflect not only their own values and the values of their culture but also the weaknesses within themselves as they struggle to lead “good lives,” in spite of all the temptations facing them. In earlier generations, Mink’s daughter, first called “Flower,” and then “LaRose” by Wolfred, eventually gives birth to another LaRose, who becomes Emmaline’s grandmother, the families of Landreaux and Emmaline having combined somewhere within the generations. The stories of the early generations of LaRose women are shown in stark contrast to the values of the American culture in which they had to live. One LaRose, Emmaline’s grandmother, attended the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, a school which took Indians off the reservation, away from their families. and out of their own culture, and “educated” them to become, essentially, servants of the Americans who wanted them to be assimilated.

During their youth, Landreaux and Romeo Puyat ran off to Minneapolis, where they watched “Little Big Man” eight times. It “affected them deeply.”

In the present generation, the stories of the Iron and Ravitch children, their resentments and reconciliations, their problems in school with bullying, and the actions they take to correct those problems occupy much of the last part of the book, and those episodes often alternate with the story of Romeo Puyat, once a friend of Landreaux, now an enemy. Love stories, sometimes complex, sometimes life-changing, develop and then fade away, and mystical moments and ghostly sightings complicate the lives of many characters. The conclusion, which takes place, appropriately, after a graduation, brings together many of the elements of the novel and many readers will find it rewarding in its mellow tones and sense of reconciliation.

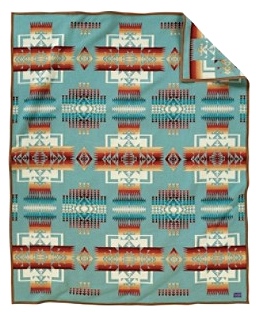

A Pendleton Chief Joseph blanket, like the one the Iron family gave to Fr. Travis in honor of their wedding, also covers him as he tries to sleep, preparing to explain why he is leaving town.

Erdrich’s descriptions, often memorable, are only as long and complex as they need to be to enliven the episodes and stories within the story here. Emmaline is described as a “branchy woman, lovely in her angularity. She was all sticks and elbows, knobby knees. She had a slightly crooked nose and striking, murky green, wolvish eyes,” a description which clearly ties her to the natural environment in which she lives. The author’s description of Landreaux going off by himself at night after the death of little Dusty, tells of a man who “made fierce attempts to send himself back in time and die…The earth was dry, the stars bursting up there. Planes and satellites winked over. The moon came up burning whitely, and at last clouds moved in, covering everything,” another description which connects with nature, without showing off. The novel will keep every reader occupied on several levels of story-telling at once, though some aspects of the novel – the girls’ volleyball experiences and competitions, for example – could have been compressed or eliminated. A few characters might also have been eliminated, one of which, the priest who replaces Fr. Travis, has a name given for purposes of “humor” which feels totally out of place, even silly. Still, the novel fascinates and and ultimately haunts on every level, and it will be on my Favorites List for the year, for sure.

ALSO by Louise Erdrich: THE ROUND HOUSE, THE PAINTED DRUM, SHADOW TAG, THE SENTENCE

Photos, in order: The author’s photo appears on https://www.pinterest.com/

Bark houses, “wigwams,” lined the river when Wolfred and the first La Rose emerged from the woods to try to make their escape from Mackinnon. http://moviemorlocks.com/

Memorabilia from the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, where Indian boys and girls learned trades valuable to the white world, may be found on https://en.wikipedia.org Double-click to enlarge.

When Landreaux and Romeo Puyat run off to Minneapolis, they spend hours at the movies, and watch LITTLE BIG MAN eight times. http://moviemorlocks.com/

As Fr. Travis suffers from insomnia before he tells his friends that he is being transferred from their church, he spends the night curled up in the blanket given to him by Landreaux and Emmaline to celebrate their marriage. https://www.pendleton-usa.com/

ARC: Harper Collins