“All the things that happened to you – there is no proof that they really did happen. Even memory does not always last. You turn your face up to the sky, inhale and exhale, close your eyes, and some little thing comes back to you for a quick second. But do not believe that moment will truly return. Everything you do in life happens for the first time and the last time. There is nothing afterward, and there won’t be anything left. If you understand that, you will be able to genuinely enjoy the things you do.” –Aunt Gracia to Menashe.

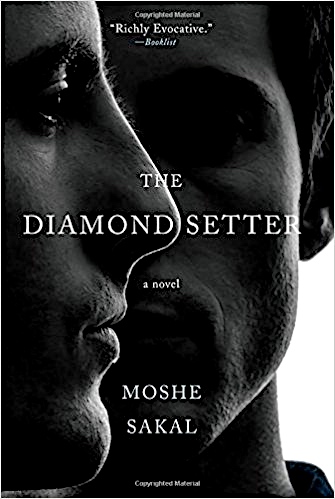

Unusual and perhaps even unique for an American audience, Moshe Sakal’s The Diamond Setter follows three generations of several interconnected families as they move though Palestine, Syria, Lebanon, and eventually Israel, following their dreams and their hopes for their families over the course of a century. Narrated in the present by Tom, much of the novel is a metafictional account of his life and his involvement in events surrounding a magnificent blue diamond which has been in the possession of members of his extended family for several generations. The diamond, despite its intriguing story, is not the primary focus here, however. Rather, it is the belief of the diamond’s possessors that the diamond has a mind of its own – and that it can affect their lives in unexpected ways. Over the generations, many have believed that the diamond is, in fact, cursed, and so they often hide it for the time that it is in their possession and live their own lives as well as they can without recourse to its “magic.”

Unusual and perhaps even unique for an American audience, Moshe Sakal’s The Diamond Setter follows three generations of several interconnected families as they move though Palestine, Syria, Lebanon, and eventually Israel, following their dreams and their hopes for their families over the course of a century. Narrated in the present by Tom, much of the novel is a metafictional account of his life and his involvement in events surrounding a magnificent blue diamond which has been in the possession of members of his extended family for several generations. The diamond, despite its intriguing story, is not the primary focus here, however. Rather, it is the belief of the diamond’s possessors that the diamond has a mind of its own – and that it can affect their lives in unexpected ways. Over the generations, many have believed that the diamond is, in fact, cursed, and so they often hide it for the time that it is in their possession and live their own lives as well as they can without recourse to its “magic.”

The novel opens in 2011, as Tom, the narrator, talks about his recent return to Israel from five years of study in New York. Though he has no experience in jewelry making, he accepts a job as an apprentice to his uncle Menashe Salomon, who owns a jewelry shop in Tel Aviv. Menashe’s favorite topic of discussion is the famous blue diamond which had originally been inset as the third eye of a statue of Shiva in India. Stolen from the statue hundreds of years ago, it became known as the “Tavernier Blue,” appearing and disappearing from India, Europe, Istanbul, then known as Constantinople, and eventually the Middle East. In 1908 or 1909, it was purchased by a sultan, who had a ten-carat piece cut off for the woman he loved in Damascus. Known as Sabakh, the smaller stone had been “taking revenge on anyone who tried to keep it.” Menashe’s father believed, however, that it was “blessed, not cursed,” that it had protected the family from disasters, first in Damascus, Syria, then in Beirut, Lebanon, and eventually in Tel Aviv, as long as they took care of it. The diamond itself, he believed, would decide when it was time for a new owner. A few weeks before the Gulf War in 1990, a family member brought the Sabakh jewel to Menashe for safe-keeping, but when the war started, it mysteriously disappeared, stolen.

The March of the Million, Sept. 3, 2011, where Fareed comes to new understanding about the Arabs and Israelis.

Almost immediately after this introduction, the reader meets Fareed, a young man who has managed to sneak out of Damascus, Syria, on a bus to Yafa (Jaffa), a section of Tel Aviv which has traditionally had a strong Arab population. He is carrying the blue diamond in his pocket and is looking for a friend he has met on-line. His walk through the city reminds him of the city’s past and of the traditional Arab-Israeli conflicts there, some of which continue to the present, even under the “unification” of Yafa (Jaffa) and Tel Aviv. When he meets Ramadan, “Rami,” a gay Palestinian he met on Grindr, he feels at home. That evening a rally called the March of the Million is scheduled. “It’s not a political demonstration,” Rami tells him. When Fareed goes to the rally, he is astonished. “No one paid any attention to a group of Arabs from Yafa calling out slogans, and no one stopped to read the Arabic on their shirts.” Eventually, “Fareed started to feel it – a love that depends on nothing, a love that does not seek fulfillment but simply exists, breezy and light….He was carried along on the waves of sound that thundered across the square…people who trod so lightly, who were not really protesting or breaking anything, but simply pouring into this space, colossal and numerous, demanding to be acknowledged, to be recognized… to flow into this urban center in rivers and streams to hug the police and to just be.”

Fareed is anxious to see the Dizengoff Center, built on what was once a slum neighborhood, now an upscale shopping center.

From this straightforward beginning, the novel becomes increasingly complex as it traces families, the jewel, and the transition of Palestine to Israel through wars and upheavals over a several decades. Information is often introduced but not fully explained, the backstory filling itself in later as more information is revealed in this experimental novel. Characters and their families – a huge number over several generations and in several different countries – dominate the action. While small incidents involving all these characters may be understandable, the big picture of who everyone is and how they are all related is held at bay until later, a sometimes frustrating experience. Fortunately, Sakal is a relatively leisurely writer who allows the reader time to contemplate and evaluate the action, the characters, and the themes, imagining futures and pasts, and not feeling pressed by a sense of urgency. Tel Aviv becomes a universal city dealing with universal issues, not one in which partisan politics invades daily life as much as the TV news would suggest. Gays are accepted without major problems in the city, and people from different cultures get along fairly well, as the March of the Million illustrates, as long the leaders of the country avoid “pinkwashing,” the practice of promoting the country as culturally friendly while ignoring the negative behavior on a larger scale. As Khaled points out, his own acceptance “goes out the window the second [I] turn up at the airport and try to get on a flight – that’s when they forget that I have an Israeli passport…and they go through my luggage like I’m a terrorist or an illegal alien.”

More than most novels, The Diamond Setter focuses on the past, with the long past of Sabakh, the blue diamond, becoming a symbol for the passage of time. Unlike its owners and the cultures in which they have lived, the diamond does not change, and the “curse” associated with it may ultimately reflect the growing pains of the society. As Fareed searches for the true owner of the diamond, he comes to fuller knowledge of himself, as does Tom, the writer of this metafiction. An Afterword updates Tom’s thinking regarding the book and his purpose in writing it. An unusual novel with a casual, deceptively relaxed attitude toward major issues, The Diamond Setter is, ultimately, a complex and challenging study of the past regarding the places all of us regard as home, especially complex when others, very different from ourselves, feel just as passionately about the same places, which are their homes, too.

Photos. The author’s photo appears on https://nyblueprint.com/

On Sept. 3, 2011, “Over 450,000 protesters attended rallies across the country…calling for social justice in what was the largest demonstration in Israeli history.” https://www.haaretz.com/1.5164105 Photo by Moti Milrod

Fareed was anxious to see the Dizengoff Center, which he had read about in a book. It had been built on the site of a former slum and was now an upscale shopping area. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dizengoff_Center. Photo by Talmoryair.

Fareed and friends walk along the beach in Tel Aviv and see the city: https://commons.wikimedia.org/

Map of the area: https://www.pinterest.com/pin/344032859005512969/