“I used to read a big padded glove-leather edition of Tennyson on lunch break every day when I worked for a mutual fund…and it was as heavy and soft as a catcher’s mitt. You could thump it with your fist. Hurl it at me, Alfred Lord, baby. Smack me with that fastball of ‘low large moon.’ “

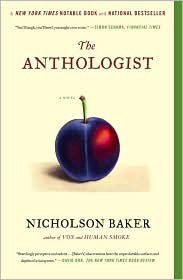

The sly hu mor of the cover, with its luscious plum, sets the tone for this rich, iconoclastic novel about poetry and the writing life. Paul Chowder, the speaker, has achieved modest success by writing “plums…That’s what I call a poem that doesn’t rhyme…We who write and publish our nonrhyming plums aren’t poets, we’re plummets.” Chowder has just compiled an anthology of poetry which he hopes will, one day, be used as the comprehensive anthology for college students and as a source of pleasure by all those who savor the music of language. Choosing the poems for the anthology was, for him, “like [being] that blond bitch-goddess on Project Runway,” and he must now write the forty-page introduction. His publisher is desperate for it, and Chowder has writer’s block.

mor of the cover, with its luscious plum, sets the tone for this rich, iconoclastic novel about poetry and the writing life. Paul Chowder, the speaker, has achieved modest success by writing “plums…That’s what I call a poem that doesn’t rhyme…We who write and publish our nonrhyming plums aren’t poets, we’re plummets.” Chowder has just compiled an anthology of poetry which he hopes will, one day, be used as the comprehensive anthology for college students and as a source of pleasure by all those who savor the music of language. Choosing the poems for the anthology was, for him, “like [being] that blond bitch-goddess on Project Runway,” and he must now write the forty-page introduction. His publisher is desperate for it, and Chowder has writer’s block.

Sitting in a shaft of light on the second floor of his barn in southern Maine, searching vainly for inspiration, he regards himself as a “study in failure.” Roz, the love of his life for the past eight years, has finally had enough of his dithering and has left him; he is in debt; his house (inherited from his parents) needs repairs; he is drowning in a sea of clutter; and he cannot focus on anything long enough to act. As he thinks about his unwritten introduction, he skitters from perceptive comments about poetry and the creative life to mundane annoyances, juxtaposing un likely subjects which keep the reader surprised and entertained. In two successive sentences, for example, he remarks that “You have to suffer to be a human being who can help people understand suffering. I have a mouse in my kitchen.” Later, while eating a messy egg salad sandwich, he “wiped some of the night’s kinked mouse droppings from the stovetop…and thought of a poet named Ed Ochester.”

likely subjects which keep the reader surprised and entertained. In two successive sentences, for example, he remarks that “You have to suffer to be a human being who can help people understand suffering. I have a mouse in my kitchen.” Later, while eating a messy egg salad sandwich, he “wiped some of the night’s kinked mouse droppings from the stovetop…and thought of a poet named Ed Ochester.”

In a voice so “human” he sounds like an alterego for author Nicholson Baker, Chowder demystifies poetry—and plums—making often hilarious comments about the structure of language, the history of poetry, the lives of famous poets, and about his own struggles. His free-flowing, not-quite-stream-of-consciousness style allows him to connect contemporary culture (and the reader) with the most serious academic subjects: “At some point,” Chowder says, “you have to set aside snobbery and what you think is culture and recognize that any random episode of “Friends” is probably better, more uplifting for the human spirit, than ninety-nine percent of the poetry or drama or fiction or history ever published.” He enjoys watching the Dick Van Dyke Show, but he also loves poets W. S. Merwin and Mary Oliver, both of whom have written poems that are explored here.

Not satiric and not anti-academic, so much as “anti-ponderous” and “anti-pompous,” Chowder is a true believer in the importance of good poetry and its ability to connect directly with our essential human nature by conveying unique visions of the world in a unique “music.” “My life is necessary,” he asserts, “because I sustain the idea of poetry through thick and thin. That’s my job.” For him, being a great poet just means that you “wrote one or two great poems. Or great parts of poems. That’s all it means.” Conferences, workshops, and readings are “nonsense…a joke.”

Not satiric and not anti-academic, so much as “anti-ponderous” and “anti-pompous,” Chowder is a true believer in the importance of good poetry and its ability to connect directly with our essential human nature by conveying unique visions of the world in a unique “music.” “My life is necessary,” he asserts, “because I sustain the idea of poetry through thick and thin. That’s my job.” For him, being a great poet just means that you “wrote one or two great poems. Or great parts of poems. That’s all it means.” Conferences, workshops, and readings are “nonsense…a joke.”

And what makes a good poem, according to Paul Chowder (and, we assume, author Nicholson Baker)? “Poetry,” he believes, “is [among other things] a controlled refinement of sobbing,” in which rhyme helps in the avoidance of pain by moving the reader along, “like chain-smoking.” His emphasis on rhyme is ironic, however, since he, himself, has had more success with free verse. He sees the rhythm of poetry as “a strolling rhythm. Or a dancing rhythm.” He illustrates the various meters, and he sets some poems to music, providing the musical notation. Poetry, in essence, is something that must be felt and heard as music, and the reader must join in its song if it is to be effective. Chock full of “a-ha” moments, the novel is a treasure trove of information and observation about poetry and poets, told with robust humor. (On my Favorites List for 2009)

Notes: The author’s photo and an audiostream interview with him appear on http://www.writersvoice.net

Baker wrote this book in his barn in South Berwick, Maine, perhaps one that resembles this Maine barn: http://www.barnyardvet.com/, a lovely site belonging to Larry Buggia, DVM, who photographs and comments on Maine life.

The LA Times has a long story about Baker and his life: http://www.latimes.com