“They were never bored with each other. They might hate each other, at least, Irene might hate Gil, while he had no idea how much he hated Irene because he was so focused on winning back her love. He really did hate her…He couldn’t see it or experience this hatred but it was there.”

In this rel entlessly domestic novel about a failed marriage, Louise Erdrich changes her focus from grand themes and the on-going history of Native American cultures to a microscopic analysis of the interactions of two people who have failed, not just in their marriage, but in virtually all their other relationships. Gil, a well-recognized, almost-great artist, is thirteen years older than Irene, who had been his student and model when she was in college and he was a teacher. Devoting virtually his entire career to paintings of Irene, he has depicted her from her almost-innocent twenties to her present life as a heavy-drinking mother of three who despises him for dominating and controlling every aspect of her life. The more angry she has become and the more passionate she has been in her rebellion, the more dramatic Gil’s portraits of her have become, with a recent one selling for six figures. Irene, who gave up her PhD studies when she married, is far more flexible, easy-going, and even irresponsible than the controlling Gil, and it is she who is closer to the children, who range in age from thirteen to six.

entlessly domestic novel about a failed marriage, Louise Erdrich changes her focus from grand themes and the on-going history of Native American cultures to a microscopic analysis of the interactions of two people who have failed, not just in their marriage, but in virtually all their other relationships. Gil, a well-recognized, almost-great artist, is thirteen years older than Irene, who had been his student and model when she was in college and he was a teacher. Devoting virtually his entire career to paintings of Irene, he has depicted her from her almost-innocent twenties to her present life as a heavy-drinking mother of three who despises him for dominating and controlling every aspect of her life. The more angry she has become and the more passionate she has been in her rebellion, the more dramatic Gil’s portraits of her have become, with a recent one selling for six figures. Irene, who gave up her PhD studies when she married, is far more flexible, easy-going, and even irresponsible than the controlling Gil, and it is she who is closer to the children, who range in age from thirteen to six.

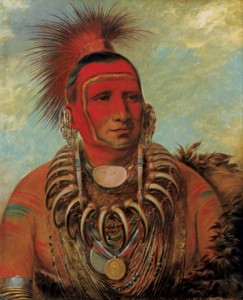

Living in a three-story house in metropolitan Minneapolis, Gil and Irene lead a comfortable life, their three children all in private schools, and Irene with enough time to work on a new PhD thesis, this one on George Catlin, the American artist who traveled the west in the 1830s and 1840s making portraits of Native Americans from as many tribes as he could find. Irene is three-quarters Native American; Gil is one-quarter, at most, yet both consider themselves Native Americans. Both have grown up in families without fathers, in homes which have not stressed their culture, and neither seems to have developed any inner resources or community ties to help deal with the crises they face on a daily basis in their crumbling marriage. Gil is strict, harsh, and even violent, with the children and with Irene; Irene is emotionally unable to leave him, though she says she has not loved him for the past six years. She finds solace in drink.

George Catlin portrait from the Nelson-Atkins Museum in Kansas City

When Irene discovers that Gil has been reading her private Red Diary, which she keeps in a file cabinet in her basement office, further proof of his need to control, she decides to take revenge, deliberately fabricating stories to shock and hurt Gil. She also opens a safety deposit box in town and makes regular trips to it to write the truth in a Blue Notebook that she has deposited there. Gil, who has always wondered where Irene goes when she is not at home, and suspects she is having an affair, soon becomes convinced not only of the affair but of the possibility that at least one of his children is not really his. As the point of view rotates from the Red Diary through the Blue Notebook to the dramatic observations of a third person, the intensity of the conflict escalates, eventually revealing such intensely personal nastiness that the reader begins to feel uncomfortable, almost voyeuristic.

Erdrich, as always, includes motifs and patterns throughout the novel which add to its significance, and here the use of shadow is pervasive. Gil often escapes to the Minneapolis Institute of Art just to sit and contemplate a painting there by Rembrandt, the master of shadow. The painting is a fine, detailed portrait of Lucretia, who, according to Livy, chose death over dishonor when she was raped by the son of the ruler. The portrait shows her in the process of disemboweling herself in front of her father and husband. By contrast, the gift paintings given by various tribes to Irene’s thesis subject, painter George Catlin, when he painted the chiefs, were all one-dimensional and contained no shadows at all. Catlin himself, however, was told that he brought shadows to the tribes when their lives changed for the worse through the introduction of European inventions (and disease). The differences in artistic preferences and styles are visual reminders of the differences in thinking and personality between Gil and Irene. In the most obvious shadow symbolism, the family spends a moonlit night outside in the snow playing shadow tag. The lack of shadows is symbolic in the conclusion.

Rembrandt’s “Lucretia” (holding the dagger in her right hand) is at the Minneapolis Institute of Art

Whereas many other Erdrich novels soar with theme, this novel is firmly grounded in domestic torments and tribulations, created with such emotional intensity that I could not help wondering about the degree to which this novel might have sprung from Erdrich’s own marriage difficulties. Others have stated outrightthat the novel is semi-autobiographical. The novel is hard to read, almost too personal, too open (and it would still feel that way even if it were completely fictional). As the conflicts develop and emotions run high, the reader is constantly aware that there are many possibilities for ending the novel and resolving the difficulties in this marriage and family. Erdrich’s choice of conclusion will disappoint many readers.

Notes: Also by Louise Erdrich, reviewed here: THE PAINTED DRUM, THE ROUND HOUSE, LAROSE, THE SENTENCE

The photo of Louise Erdrich is by Dawn Villella of the Associated Press, and appears with a New York Times review of Louise Erdrich’s The Red Convertible, a story collection published in 2009. www.nytimes.com/2009

The George Catlin portrait is from the Nelson-Atkins Museum in Kansas City: www.nelson-atkins.org.

For those interested in the autobiographical aspects of this novel, Salon has an article here about the marriage of Louise Erdrich and Michael Dorris: www.salon.com/april97