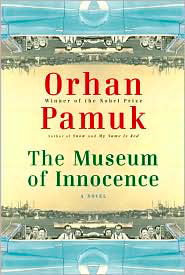

Note: Orhan Pamuk was WINNER of the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2006.

“It seemed to me now that I was going to be able to enjoy…good fortune–partaking of all the pleasures of a happy home life with a beautiful, sensible, well-educated woman, and at the same time enjoying the pleasures of an alluring and wild young girl…”

Turkish author Orhan Pamuk’s latest novel soars to new heights, taking fiction itself to an exhilarating new level and blurring the lines between fiction and reality in new ways. Ostensibly the obsessive love story of Kemal Basmaci, age thirty, for a beautiful shop-girl named Fusun, eighteen, the novel explores much more than that, examining not only the physical passion which underlies their relationship and their lives, but also broader themes involving the connections between love and memory, between memory and reality, and between love and reality.

Turkish author Orhan Pamuk’s latest novel soars to new heights, taking fiction itself to an exhilarating new level and blurring the lines between fiction and reality in new ways. Ostensibly the obsessive love story of Kemal Basmaci, age thirty, for a beautiful shop-girl named Fusun, eighteen, the novel explores much more than that, examining not only the physical passion which underlies their relationship and their lives, but also broader themes involving the connections between love and memory, between memory and reality, and between love and reality.

Including metafictional elements in the telling of Kemal’s story, Pamuk himself participates in the story as both a fictional and a real character, adding another level to the story. In a unique tour de force, the author is now creating a (real) Museum of Innocence in Istanbul, located in the house in which Fusun and her fict ional family “lived.” In essence, we have author Pamuk creating a fictional story about fictional people, whose real house and the objects in it (described fully in the fictional story) become a real physical memorial to the fictional characters in the love story which Kemal has “asked” Pamuk to write for him. In creating a real-life memorial to the lives of fictional characters, then, Pamuk is ultimately freeing the reader’s imagination from the constraints of fiction–giving “reality” greater meaning by allowing fiction to be part of it. The reader’s memories of the novel’s characters will endow the museum with life as visitors discover items which have been important in the story. The museum, in turn, will make the words on paper become the “real” people who have used these real objects.

ional family “lived.” In essence, we have author Pamuk creating a fictional story about fictional people, whose real house and the objects in it (described fully in the fictional story) become a real physical memorial to the fictional characters in the love story which Kemal has “asked” Pamuk to write for him. In creating a real-life memorial to the lives of fictional characters, then, Pamuk is ultimately freeing the reader’s imagination from the constraints of fiction–giving “reality” greater meaning by allowing fiction to be part of it. The reader’s memories of the novel’s characters will endow the museum with life as visitors discover items which have been important in the story. The museum, in turn, will make the words on paper become the “real” people who have used these real objects.

However multilayered the novel may be, it is also playful and great fun to read, as Pamuk effortlessly involves the reader in the story, which opens in 1975. Thirty-year-old Kemal, from a wealthy family, is busy getting ready for his lavish engagement party to Sibel, an equally prominent young woman of his own “class” and someone he truly loves. When he meets Fusun a shop-girl to whom he is passionately attracted, and who is also passionately attracted to him, he acts the way his father and uncles have always behaved in the past–he believes that he can marry Sibel and lead a social life among other people of his “class,” while still having an active private life with Fusun, a girl of a different “class” that he cannot live without. Pamuk clearly depicts the sexual mores of Istanbul in 1975, and emphasizes the differences from western life from the same era.

The ensuing action of the novel takes place over the next thirty-one years (The plot details mentioned here are at the very beginning of the book and do not constitute spoilers.) Kemal, weak, “entitled,” and selfish, cannot prevent his engagement to Sibel from being announced–Sibel would be an outcast if he chose to follow his heart for Fusun–and he is devastated when Fusun shows up at the engagement party with her family. What Kemal never expects, however, considering the depth of Fusun’s love for him, is that she will then vanish, not just from his lif e but, seemingly from all the neighborhoods in which she has lived. Absolutely obsessed with her, Kemal begins to exhibit signs of severe emotional problems as the wedding gets closer, and he and Sibel go off to a secluded, private “yali,” a beach house on the water, where they live for months trying to rekindle the love that they once had.

e but, seemingly from all the neighborhoods in which she has lived. Absolutely obsessed with her, Kemal begins to exhibit signs of severe emotional problems as the wedding gets closer, and he and Sibel go off to a secluded, private “yali,” a beach house on the water, where they live for months trying to rekindle the love that they once had.

Kemal continues to live out his obsession by befriending Fusun’s parents, becoming increasingly isolated from his “real” life as a wealthy businessman, and collecting every object, including 4213 cigarette butts, which Fusun has ever touched. His kleptomania at her parents’ house becomes worse as time progresses, and he soon has the beginnings of a museum to Fusun in an apartment that his mother uses for storage. He also becomes involved in movie production, another level of Pamuk’s exploration of fiction vs. reality, and though this section might have benefited from judicious pruning, it does add to the thematic development and effectively suggests elements similar to those in Plato’s Allegory of the Cave.

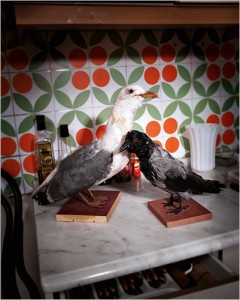

Birds which Pamuk is painting for display in the museum. See quotation from NYTimes in Photo notes below.

What gives the book its final power is the re-appearance of Orhan Pamuk as a character in the novel’s conclusion, as he explains his relationship with Kemal (he insists in interviews that he is not Kemal) and his decision to start a real Museum of Innocence in Fusun’s family house. This decision gives this novel a level of reality which is unique in fiction, one which I found thrilling to contemplate. Compelling to read, filled with unusual characters, and structured to achieve the maximum possible thematic effect, The Museum of Innocence is a breath-taking novel, the best I’ve read by Pamuk, and one he will have a hard time bettering.

ALSO by Pamuk: SNOW

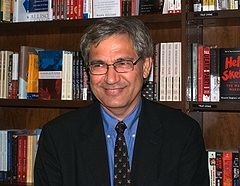

Photos, in order: The author’s photo appears on his Wiki page: http://en.wikipedia.org

The narrow house on the corner of Cucurcuma Cd, the location of Fusun’s home and the site of the future Museum of Innocence, which the author plans to open in the fall of 2010, is shown here: http://jb-passages.blogspot.com

The photo of the tricycle which once belonged to Kemal and was given to distant cousin Fusun is by Olaf Becker for an article in the NYTimes Magazine: www.nytimes.com

According to Pamuk in the New York Times: Fusun, the character with whom I strove to identify in this novel, passes time in her marriage by making paintings of birds. As it happens, I was a painter in my youth. In my museum, I will show the popular birds of Istanbul, which Fusun fastidiously paints one by one, but I will paint them myself. This is a stuffed seagull and crow I have in my office that help me as I prepare the paintings for the museum. Once in a while other crows come to my balcony to peer in at this one. http://www.nytimes.comslideshow_5.html