Note: Jerzy Pilch has been nominated for Poland’s highest literary award, the NIKE Literary Award (Nagroda Literacka NIKE) four times. He won it in 2001 for THE MIGHTY ANGEL.

“In those days I was never parted from my pencil and notebook. The desire, stronger than anything else, to record words and sentences that had just been uttered, or would be in a moment, directed my every step, waking and sleeping. I would place the notebook and pencil on the nightstand, and…[at] 2:00 or 3:00 in the morning, when the Antichrist himself touched my featherbed with a wet wing…I would reach for notebook and pencil and record the word or sentence that brought relief.”

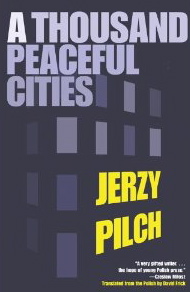

Set in 1963 in Wisla, the rural Polish town where author Jerzy Pilch himself grew up, A THOUSAND PEACEFUL CITIES feels as much like a real memoir as a satirical, fictional retelling of life in Poland in the years preceding the Student Revolt of 1968. In 1963, the Communist party is in power, and the country is under Soviet influence but not control. A strong, independent spirit and the residual respect of the populace for First Secretary Wladysaw Gomulka, who successfully challenged Nikita Khrushchev in 1956, has encouraged the populace to live as they have always lived, though economically they are becoming poorer. The churches, both Catholic and Protestant, are still open and are a major part of life, not just in terms of religion but in the communities’ regular social gatherings. Under the increasing influence of the Soviets, however, Gomulka has become more dictatorial, imposing further limits on his people.

in Wisla, the rural Polish town where author Jerzy Pilch himself grew up, A THOUSAND PEACEFUL CITIES feels as much like a real memoir as a satirical, fictional retelling of life in Poland in the years preceding the Student Revolt of 1968. In 1963, the Communist party is in power, and the country is under Soviet influence but not control. A strong, independent spirit and the residual respect of the populace for First Secretary Wladysaw Gomulka, who successfully challenged Nikita Khrushchev in 1956, has encouraged the populace to live as they have always lived, though economically they are becoming poorer. The churches, both Catholic and Protestant, are still open and are a major part of life, not just in terms of religion but in the communities’ regular social gatherings. Under the increasing influence of the Soviets, however, Gomulka has become more dictatorial, imposing further limits on his people.

By 1963 the Catholic Church has come under political fire, the press is being censored, and students and intellectuals are being persecuted. The residents of Wisla whom we meet in this novel, however, see the end of Communism as an inevitability–something that will certainly happen as a matter of course, despite Gomulka. As a result, they are unwilling to rebel to promote this “inevitability,” preferring to remain safely within their “thousand peaceful cities.”

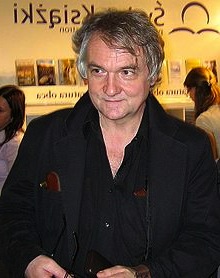

Regarded as “the hope of young Polish prose” in his own country, Jerzy Pilch is difficult to separate from the narrator of this novel—Jerzyk (“little Jerzy”), a teenager who has already made a lifelong commitment to writing—and to finding out more about the world, and especially the mysterious world of love. At the outset of the novel, the reader immediately discovers that Jerzyk’s father and his father’s friend, Mr. Traba, an alcoholic former clergyman, plan to kill First Secretary Wladysaw Gomulka in Warsaw. They had, at first, thought of killing Mao Tse-tung to make a statement but decided it was impractical: “Better a sparrow in the hand than Mao Tse-tung on the roof.” Traba has always wanted to do something for humanity, and he believes that this act will finally give meaning to his life, making it “definitively ordered.”

What follows is a wild ride through rural Poland in 1963—a novel that is, by turns, hilarious, thoughtful, filled with metaphysical and dialectical argument, and embellished with lyrical details from the natural world. Throughout the entire novel, irony and absurdity dominate, but these seem somehow “ordinary” here because they are couched in the reality of everyday details. For Jerzyk, the best part of the scheme to kill Gomulka is that he will have a part in it, a chance to escape his normal life in Wisla and perform an act of national significance. “For the first time in my life I understood that if I weren’t given wings, I would not be able to go a step further…” and he is desperate to gain his wings. Rejoicing in the fact that he is the one who will be entrusted to carry the Chinese crossbow with which they will kill Gomulka when they finally get to Warsaw, he prepares for the trip and its aftermath.

In a scene that resembles classical farce, the three conspirators go to the church and defend their plans against every possible moral, ethical, and religious argument the community can offer. The conspirators are Protestants—Lutherans—in a largely Catholic country, and “Not taking part is the chief characteristic of Protestants, especially in Poland.” In a classic example of twisted logic, Traba announces that “As a Protestant who doesn’t exist, I can kill without hesitation, since the act will remain in the realm of nothingness. If as some say, Poland is a Catholic country, then, there you have it! It follows clearly from this that, if lese-mageste is perpetrated in a Catholic country by a non-Catholic, that is by nobody, or by a foreigner, then the good name of our holy fatherland, the holy mother of all fatherlands, to whom the tradition of assassinating kings is foreign, will remain unsullied, and at the same time she will gain the name of one who, as the first of the oppressed, raised her hand against the usurper,” an argument Traba refers to as “the dialectic of my patriotism.”

In a scene that resembles classical farce, the three conspirators go to the church and defend their plans against every possible moral, ethical, and religious argument the community can offer. The conspirators are Protestants—Lutherans—in a largely Catholic country, and “Not taking part is the chief characteristic of Protestants, especially in Poland.” In a classic example of twisted logic, Traba announces that “As a Protestant who doesn’t exist, I can kill without hesitation, since the act will remain in the realm of nothingness. If as some say, Poland is a Catholic country, then, there you have it! It follows clearly from this that, if lese-mageste is perpetrated in a Catholic country by a non-Catholic, that is by nobody, or by a foreigner, then the good name of our holy fatherland, the holy mother of all fatherlands, to whom the tradition of assassinating kings is foreign, will remain unsullied, and at the same time she will gain the name of one who, as the first of the oppressed, raised her hand against the usurper,” an argument Traba refers to as “the dialectic of my patriotism.”

Pilch keeps his novel, however funny, on a high literary plane, his la nguage, even his dialogue, elegantly written and artful. A student of philology, the author fills his novel with biblical and historical argument, at the same time that he develops memorable characters. On the way to kill Gomulka, for example, Jerzyk’s father and Traba tell stories, which prompts Jerzyk to note that “The invention of stories about oneself is the duty and irresistible temptation of the true man. The made-up story is the song of his life and death. The story of the loser, the invented story of the loser, is the sign of the winner.” Challenging and intriguing, at the same time that it is often hilariously funny and crazily absurd, Pilch’s third novel to be translated into English is a memorable visit to 1960s Poland as the country and the author are about to reach a turning point.

nguage, even his dialogue, elegantly written and artful. A student of philology, the author fills his novel with biblical and historical argument, at the same time that he develops memorable characters. On the way to kill Gomulka, for example, Jerzyk’s father and Traba tell stories, which prompts Jerzyk to note that “The invention of stories about oneself is the duty and irresistible temptation of the true man. The made-up story is the song of his life and death. The story of the loser, the invented story of the loser, is the sign of the winner.” Challenging and intriguing, at the same time that it is often hilariously funny and crazily absurd, Pilch’s third novel to be translated into English is a memorable visit to 1960s Poland as the country and the author are about to reach a turning point.

Notes: The photo of the author appears on http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jerzy_Pilch

The charming photo of Wisla, in the southwest corner of Poland, is by Ania i Olek and appears here, with more photos from the area: http://my.opera.com. Perhaps the meeting at the church occurred in the town’s central church in the photo.

The photo of Gomulka and Khrushchev is from http://perspective.usherbrooke.ca. Jerzyk’s father’s job problems resulted from actions/nonactions by Khrushchev.