“These days the dead are more fortunate than the living. What are we to do? We’re on the eve of destruction. Men have lost all sense of honor. Power has become their faith instead of faith being their power. There are no longer any courageous men.”

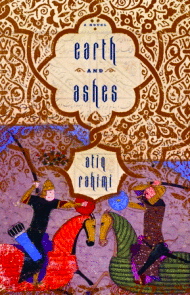

Earth and Ashes, a small novella, packs more feeling and more power into its few pages than most other books do in hundreds of pages, and few, if any, readers will emerge from it unscathed. Author Atiq Rahimi, an Afghan national now living in France, has recreated the Afghanistan he remembers when it was occupied by the Russians (1979 – 1989). He was seventeen at the time, and life has not improved much for the populace since then. Only the enemies have changed, and they now include many factions from within. Rahimi’s bleak picture of life in the farming village of Abqul includes the occupiers’ casual murder of individuals, the decimation of families, the annihilation of villages, and ultimately the obliteration of whole cultures going back to ancient times. Without preamble or any lengthy setting of the scene, the author introduces a main character who is faced with a family crisis from which he may never recover, then tells that story in plain, direct, and straightforward language which gains impact from its very simplicity.

Earth and Ashes, a small novella, packs more feeling and more power into its few pages than most other books do in hundreds of pages, and few, if any, readers will emerge from it unscathed. Author Atiq Rahimi, an Afghan national now living in France, has recreated the Afghanistan he remembers when it was occupied by the Russians (1979 – 1989). He was seventeen at the time, and life has not improved much for the populace since then. Only the enemies have changed, and they now include many factions from within. Rahimi’s bleak picture of life in the farming village of Abqul includes the occupiers’ casual murder of individuals, the decimation of families, the annihilation of villages, and ultimately the obliteration of whole cultures going back to ancient times. Without preamble or any lengthy setting of the scene, the author introduces a main character who is faced with a family crisis from which he may never recover, then tells that story in plain, direct, and straightforward language which gains impact from its very simplicity.

Dastaguir, a grandfather accompanied by his small grandson, is walking along a dusty road from his town of Abqul toward the coal mines of Karkar. The Russians, after looting his village one day, had returned the next day to burn it to the ground. “They didn’t spare a single life…I don’t understand why God saw fit to punish us.” Dastaguir, upon his return to his village has discovered that his wife, son, daughter-in-law, their children, and the mother of his grandson Yassin, the child, along with all the other villagers, are now dead. Though little Yassin has escaped the fires, he is now totally and suddenly deaf, and he is confused. He does not understand why jujube stones which used to click against each other when he played with them, are now silent, why Dastaguir will not answer him when he speaks to him, and why the world is suddenly so quiet.

The “action” takes place as Dastaguir and Yassin are walking on a mission to find Dastaguir’s surviving son Murad, Yassin’s father, who fled the village to work in the mines four years ago, and who has returned to the village only a few times since then. Dastaguir hopes Murad will reconnect with his son, especially now that the village and the rest of the family are gone. As they walk, Yassin demands help, begs for water, which is in short supply, and asks for and then does not eat apples or stale bread. Dastaguir himself seems to survive on naswar, a kind of moist snuff.

Talking to himself const antly through the miles, he takes a distanced view of himself, referring to himself always as “you.” “To whom are you speaking?” he asks himself. “To Yassin? He can’t even hear the sound of stones, let alone your feeble voice.” He imagines meeting with Murad at the mine and has nightmares which combine ancient stories with the events of his village. And when a shopkeeper tries to be friendly, Dastaguir has to remind himself to respond–“You wanted to talk to anyone about anything. Now, here is someone who’ll listen to what lies in your heart, whose look alone is a comfort. Say something!”

antly through the miles, he takes a distanced view of himself, referring to himself always as “you.” “To whom are you speaking?” he asks himself. “To Yassin? He can’t even hear the sound of stones, let alone your feeble voice.” He imagines meeting with Murad at the mine and has nightmares which combine ancient stories with the events of his village. And when a shopkeeper tries to be friendly, Dastaguir has to remind himself to respond–“You wanted to talk to anyone about anything. Now, here is someone who’ll listen to what lies in your heart, whose look alone is a comfort. Say something!”

As he contemplates his God, he decides in his desperation that “the reality is that God isn’t concerned with you,” and then realizes that he has blasphemed: “Damn the temptations of Satan. Damn you.” He continues on his walk.

Throughout the novella, the author mentions the Persian epic The Book of Kings by Ferdusi, which “interweaves Persian myths, legends, and historical events to tell the history of Iran and its neighbors from the creation of the world to the Arab conquest in the seventh century.” Three characters in that book loosely parallel characters and actions in this novella, and as Dastaguir begins to learn about the power of the occupiers to change the thinking and commitments of their young male subjects, the parallels become obvious here.

For a novel in which the “actions” that involve the reader are mostly “reactions to” past events, with very little new activity or plot, the author manages to inspire some powerful emotional moments. The reader cares for Dastaguir because he reacts with universal human feelings. Yassin, of course, is an innocent, but like all children, he wants what he wants and is willing to cry and manipulate to get it, something that Dastaguir tolerates because Yassin is still confused about his deafness and its permanence. The sympathy generated for the characters makes the bleak ending even more powerful. With its simplicity and its careful choice of the right detail at the right moment, Earth and Ashes resembles some of the very best short stories by Steinbeck, Hemingway, and Andre DuBus, all of whom compress, compress, and then compress some more the images and details with which the reader comes to a full understanding of the author’s purpose.

ALSO by Atiq Rahimi: A CURSE ON DOSTOEVSKY

Photos, in order: The photo of the author by Helene Bamberger/Editions Pol is posted here: http://www.independent.co.uk

The photo of the weeping boy and the man, by Joel Saget/AFP/Getty Images, is part of a pictorial essay essay on Afghanistan posted on http://www.boston.com

A coal miner from the Karkar coal mines, where Murad is working, is photographed by Ahmad Massood/REUTERS, as part of a photo essay here: http://www.boston.com