“There should be some way…to tell [this girl] what [she] has discovered. Which is what? That friendships end? That love dissipates? That people die? That there is nothing to trust in this uncertain life? Happiness, love, friendship, even one’s own body—all the enduring bonds finally cannot endure. Nothing is secure. Nothing keeps. What is the good of knowing that?”

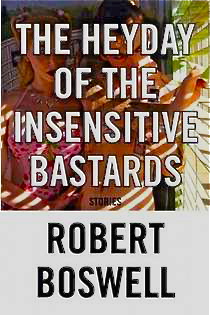

In this collection of s tories about life’s uncertainties, Robert Boswell picks up his characters like mechanical toys and winds them up tight, and just when they are at maximum tension, he twists the key one more turn, guaranteeing that they will unwind noisily, out of control. Virtually all his characters are losers. A woman, having lost her disabled husband, now finds that she has also lost her best friend. A housecleaner has been abandoned by her husband. An attention-seeking motel manager demands that a patron strip search her. A needy young man goes broke while in the thrall of a fortune teller. A priest tries to help a pathetic family by offering a “story to have faith in, even if he cannot entirely believe it.”

tories about life’s uncertainties, Robert Boswell picks up his characters like mechanical toys and winds them up tight, and just when they are at maximum tension, he twists the key one more turn, guaranteeing that they will unwind noisily, out of control. Virtually all his characters are losers. A woman, having lost her disabled husband, now finds that she has also lost her best friend. A housecleaner has been abandoned by her husband. An attention-seeking motel manager demands that a patron strip search her. A needy young man goes broke while in the thrall of a fortune teller. A priest tries to help a pathetic family by offering a “story to have faith in, even if he cannot entirely believe it.”

The stories are sometimes bleak, but they are always haunting. The characters are just one twist away from the normal, the safe, and the real, feeling instead to be “different,” irrational, sometimes dangerous, and even frightening. They have been buffeted by fate, often inspired by their own misdeeds, and they are, as a group, naïve, thoughtless, and sometimes ignorant. Most of them have memories from childhood which lurk to torment them, and they have done little to change their behavior and virtually nothing to improve their present situations. Lacking values and commitment to the larger world, most are self-indulgent, living empty lives.

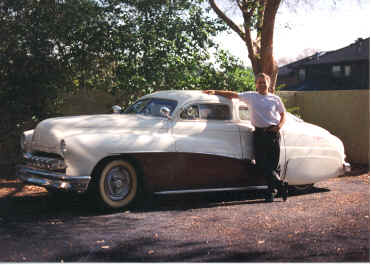

Startling stories grow from seemingly ordinary events. In “Lacunae,” Paul Lann has driven two hundred miles across the desert from Tucson to pick up his father, who is being released from the hospital after his ninth stroke, and drive him to his family’s home nearby. His father’s awareness of his surroundings comes and goes, “like a haunting,” and he speaks in two voices, his normal voice and his “bad voice.” Paul has had a miserable marriage, and the one constant in his life has been an old Mercury sedan. Faced with his father’s precarious health and a final chance to reunite with his wife and her child, Paul must choose whether to stay or go.

“A Walk in Winter” features a young man who has returned to Chapman, North Dakota, in the middle of winter. Riding with the sheriff, he is on his way to identify his mother’s frozen remains. His mother had disappeared following an argument with her husband when the boy was ten, and he has been brought up by his aunt. When he sees the detached jawbone, he remembers the last time he saw his parents, suddenly shocked into understanding all the missing pieces of his early life. He remembers an accident he had five years earlier, with his girlfriend’s child in the car, wondering whether he, himself, will be “one of the stones on which [this small boy’s] character was built.”

“A Walk in Winter” features a young man who has returned to Chapman, North Dakota, in the middle of winter. Riding with the sheriff, he is on his way to identify his mother’s frozen remains. His mother had disappeared following an argument with her husband when the boy was ten, and he has been brought up by his aunt. When he sees the detached jawbone, he remembers the last time he saw his parents, suddenly shocked into understanding all the missing pieces of his early life. He remembers an accident he had five years earlier, with his girlfriend’s child in the car, wondering whether he, himself, will be “one of the stones on which [this small boy’s] character was built.”

In the title story, a novella, main character Keen begins his story: “I was in that drifting age between the end of college (sophomore year) and the beginning of settling down (the penitentiary)…” He and his friend Clete, both addicted to mushrooms and almost any other illegal substance they can get, move in with a friend who is house-sitting for the summer and watching a family’s two dogs. Several other freeloaders, both male and female also move in, and to support their habits, they sell, one by one, the entire contents of the house. Dividing the story into an ironic ten-step program, the novella begins with a “Happier Time,” and progresses through “Considering Others,” and “Accepting Responsibility,” to “Understanding Mistakes,” “Mental Health,” and “What I’ve Learned.” The ironies of these titles become obvious as two members of the household die and two others get married.

Boswell makes every word count here, choosing his descriptors of people and objects so carefully that the reader can instantly see the pictures the author creates—“His [car] window held a cornea of ice,” and on a cold day, “The oak limbs creaked their wooden misery.” “Her husband…had about him the ordinariness often ascribed to serial killers. Sort of a bland Regis Philbin…” and “The bus driver slumps behind the steering wheel, his head bulging beneath his city cap as if it were screwed on too tight.” His characters, just one notch beyond normal and one notch more disturbed, are familiar and understandable, regardless of how strange they may be, and the intensity of the stories keep the reader’s interest at high pitch.

Ultimately, t hese unforgettable characters with their haunted and damaged lives, leave the reader uncomfortable with their ironies. Damaged as many characters are, they are close enough to ourselves and those we know to feel familiar to us. Here in this outstanding collection, Boswell creates a variety of personalities in a variety of tension-filled situations, speaking with a variety of voices about the dilemma of being alive.

hese unforgettable characters with their haunted and damaged lives, leave the reader uncomfortable with their ironies. Damaged as many characters are, they are close enough to ourselves and those we know to feel familiar to us. Here in this outstanding collection, Boswell creates a variety of personalities in a variety of tension-filled situations, speaking with a variety of voices about the dilemma of being alive.

ALSO by Robert Boswell: Tumbledown

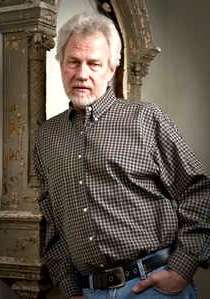

Photos, in order: The author’s photo is from his website: www.robertboswell.com

An old Mercury, one character’s prized possession, is here: www.acmeron.com

The desert road from Tucson is from www.homeaway.com

The incredible snows of North Dakota, photographed by a county emergency manager in Minot, North Dakota, may be found here: http://www.endofthenet.org/archives/5506