“The Merchant Clerk,” a photographic portrait by famed German photographer August Sander in 1912, shows a young man dressed in his best formal clothes, looking out innocently at the world he is facing and the world war that may soon take his life. Contemporary poet Adam Kirsch, imagining this man’s life, asks,

“How to explain the living radiance

That flashes forth from this dead man, who seems

Not to believe in insignificance,

As if he knew we all will be redeemed?”

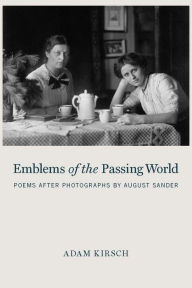

The same question may be asked of all forty-five other photographic portraits by Sander, a world-renowned photographic artist (1876 – 1964). Upon contemplating Sander’s portraits from 1910 through the 1940s, poet Adam Kirsch has invented lives for the real people behind these portraits, none of whom are named, and all of whom are identified in Sander’s work by only a few words regarding their places in society. In Part I, they are all working class people identified by their jobs; in Part II, they are people of the middle and professional classes, educated and often talented; in Part III, they are wives and working women; and in Part IV, they are people who represent the future and its terrible uncertainties. The cover photo here, identified as “Small-Town Women,” imagines two women thinking about “Business and law the church and government,/Making a living, having a career–/Things that their brothers and their husbands spent /Their lives on seem unnecessary here,/ In this small parlor where the window’s shut/Airtight, and only beams of light convey/News of the world beyond the haven that/They are condemned to occupy all day.”

The same question may be asked of all forty-five other photographic portraits by Sander, a world-renowned photographic artist (1876 – 1964). Upon contemplating Sander’s portraits from 1910 through the 1940s, poet Adam Kirsch has invented lives for the real people behind these portraits, none of whom are named, and all of whom are identified in Sander’s work by only a few words regarding their places in society. In Part I, they are all working class people identified by their jobs; in Part II, they are people of the middle and professional classes, educated and often talented; in Part III, they are wives and working women; and in Part IV, they are people who represent the future and its terrible uncertainties. The cover photo here, identified as “Small-Town Women,” imagines two women thinking about “Business and law the church and government,/Making a living, having a career–/Things that their brothers and their husbands spent /Their lives on seem unnecessary here,/ In this small parlor where the window’s shut/Airtight, and only beams of light convey/News of the world beyond the haven that/They are condemned to occupy all day.”

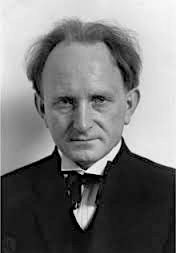

Author photo by Don Pollard, W.W.Norton

In his revelatory introduction, poet Kirsch discusses the differences between snapshots and portraits like Sander’s – composed, austere, and independent of time. Snapshots, he emphasizes, are “meant to preserve not just an image but the moment of its taking; its intention is not documentary so much as memorial, and when we look at it we are remembering more than we are actually seeing.” A snapshot encourages remembering on the part of the viewer, who brings his memories to everything he knows about the snapshot. “Unlike a work of art, [a snapshot]” Kirsch says, “is mortal and private.” In Sander’s photographic portraits, where the subjects have no names, one cannot help trying to incorporate them into our own memories and what we have come to know within our own lives. In a wonderful tribute to Sander, Kirsch comments that “In [his photographs] we see what is ordinarily hidden from us – the way we ourselves appear, and will appear to posterity, as types, when we stubbornly insist on experiencing ourselves as individuals—as both subjects and objects.”

Of photographer Sander himself, Kirsch writes:

Of photographer Sander himself, Kirsch writes:

“The photograph of the photographer

Does not resort to posing him with tools,

The flashbulb or the lens that might declare

He is his job, like everybody else

Who passed before the categorical,

Silent Tribunal of his black and white

Whose verdict is as unappealable

And little to be argued with as sight:

What you appear to be is what you are,

Despite the pleas of subjectivity

Whispering there is more to you by far

Than the mere object you’re compelled to be

As soon as his remorseless shutter clicks—

Unless, perhaps, he secretly agrees

A man cannot be known by how he looks,

Only by the infinity he sees.”

Widow with her Sons c.1921, printed 1990 August Sander 1876-1964 ARTIST ROOMS Tate and National Galleries of Scotland. Lent by Anthony d’Offay 2010 http://www.tate.org.uk/art/work/AL00018. Click to enlarge.

Focused as they are within Germany between 1910 and 1950, Sander’s photographs illustrate a succession of real people who survived World War I, Germany’s defeat, the Weimar Republic, the Third Reich, World War II, and/or Germany’s defeat, “a succession of traumas and horrors that defined Germany in the twentieth century.” As the reader views each of these photographs and then studies the poems with which Adam Kirsch has tried to bring them all alive, we begin to see these people as more than the physical presences which Sander recorded, and more as real people who have much in common with all of us. Instead of spending more time here “talking about” the photographs and poems, I am posting some photographs and the poems Kirsch has written for them so that the reader is in a position to see just how engaging and even hypnotic this combination of the visual and the imagined is for the reader.

One of the most powerful portraits and poems is for “The Butcher’s Apprentice,” 1911 – 1914, photographed during the time just before World War I destroyed the peace. Kirsch describes him in a different role from his occupation here.

“The Butcher’s Apprentice.” Both the photograph and the poem have been printed by the Poetry Foundation through Poetry Magazine. Click to enlarge.

The Butcher’s Apprentice, 1911–1914 by August Sander

The high white collar and the bowler hat,

The black coat of respectability,

The starched cuff and the brandished cigarette

Are what he has decided we will see,

Though in the closet hangs an apron flecked

With bits of brain beside the rubber boots

Stained brown from wading through the bloody slick

That by the end of every workday coats

The killing floor he stands on. He declines

To illustrate as in a children’s book

The work he does, although it will define

Him every time the photograph he took

Is shown and captioned for posterity —

Even as his proud eyes and carriage say

That what he is is not what he would be,

In a just world where no one had to slay.

And reflecting a completely different subject, that of a “Middle-Class Child,” Kirsch says,

The rain of gifts in which the child has grown

Can be deduced from her small bright medallion,

Her brand-new shoes, her black dress gay with braid,

But most from the instinctive way she’s laid

Her hands contentedly across her lap,

Confident she won’t need to hit or grab

To get the good things life has promised her.

How could she know it’s dangerous to wear

A smile so merry and self-satisfied,

When all her life has been arranged to hide

The possibility of nemesis

And put off the discovery of loss?

Who could rebuke her when she acts as if

She thought she were herself the greatest gift?

Kirsch’s poetry seems to blend with Sander’s photographs almost seamlessly, adding a kind of depth to them which provides hints of higher meaning and which gives the reader new ways of seeing the portraits. People who are not fond of modern poetry may find that if they read these poems twice, paying attention to the flow of the language from one line to the next, that they may love these poem/photograph combinations as much as I do. This is an unusual combination of photography, poetry, and the stories Kirsch creates within the poems which suggest new ways to view the photographs, some of them ineffably sad, many ironic, and a few sentimental, and I am thrilled to have had this introduction to a world-class photographer of immense talent and reputation and the poems by Adam Kirsch which makes many of them come alive in new ways.

Credits: The author’s photo by Don Pollard/W.W. Norton appears on http://www.nytimes.com/

August Sander’s portrait is from https://en.wikipedia.org/

The photograph of the Widow and Her Sons, 1921, belongs to http://www.tate.org.uk

Both the photograph and the poem of “The Butcher’s Apprentice” have been printed by the Poetry Foundation through Poetry Magazine: http://www.poetryfoundation.org

The poem of “The Middle-Class Child” is from http://www.otherpress.com and the photograph of “The Middle-Class Child” is from http://www.moma.org/

ARC: Other Press