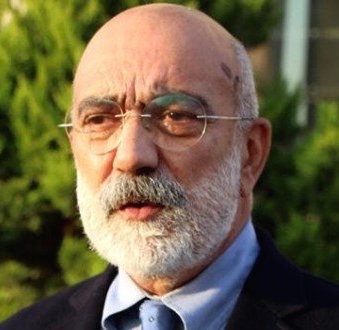

Note: Ahmet Altan, Turkish journalist and author of nine novels, was WINNER of the Prize for the Freedom and Future of the Media from the Sparkasse Leipzig in 2009. In 2011, he was AWARDED the international Hrant Dink Award. He is currently jailed for criticizing the government of Turkey.

“God has a savage sense of humour. And coincidence is his favourite joke. And life is nothing but a string of coincidences. You see, I was a stranger in town. I came from a big city, far away. I stayed there to write a book about murder. And so what if I turned out to be the killer? I’ll simply put it down as God’s work, another one of his cruel coincidences, taunting his own creation.”

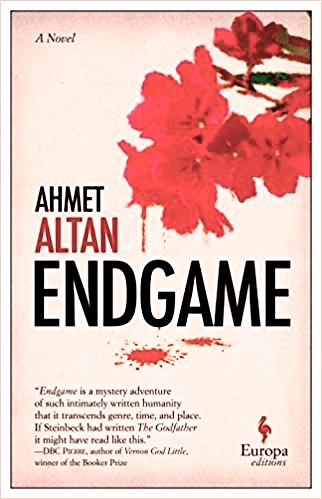

In his first novel to be translated into English, author/journalist Ahmet Altan sets his novel in a small, unnamed town in rural Turkey to which an unnamed Turkish author has gone to retire and work on a new book. In the first two pages of this book, however, the reader learns that that author has committed a murder, though the victim is also unnamed. What follows is a novel which is both clever and exasperating, as the main character inserts himself into the life of a small town with long-standing rivalries and intrigues and becomes, himself, a part of the frenzied action and reaction to slights and betrayals, both real and imagined. As the novel opens, the author is sitting outside, apparently in the final hours of his life, waiting to be apprehended for murdering a resident and contemplating the meaning of life and his responsibility for his own actions – an irony, since he also believes his predicament to be “God’s work.” God, after all, “has a savage sense of humour. And coincidence is his favorite joke.”

In his first novel to be translated into English, author/journalist Ahmet Altan sets his novel in a small, unnamed town in rural Turkey to which an unnamed Turkish author has gone to retire and work on a new book. In the first two pages of this book, however, the reader learns that that author has committed a murder, though the victim is also unnamed. What follows is a novel which is both clever and exasperating, as the main character inserts himself into the life of a small town with long-standing rivalries and intrigues and becomes, himself, a part of the frenzied action and reaction to slights and betrayals, both real and imagined. As the novel opens, the author is sitting outside, apparently in the final hours of his life, waiting to be apprehended for murdering a resident and contemplating the meaning of life and his responsibility for his own actions – an irony, since he also believes his predicament to be “God’s work.” God, after all, “has a savage sense of humour. And coincidence is his favorite joke.”

The town itself, located in the Turkish mountains, is dominated by the remains of an ancient church at the top of a hill, and much of the action of the town over the generations has been related to the belief that a fabulous treasure is buried in the ruins there. Gradually, through flashbacks, the town’s characters and their roles in the action become clearer. The men control the life of the town, but they are divided into two groups, competing with each other for influence over the rest of the male population and using murder as a favorite – and very casual – weapon whenever one or another of the leaders becomes frustrated with the pace or direction of life. Mustafa Gurz, the corrupt mayor, allied with the violent Oleander Ramiz, becomes a friend, of sorts, with the speaker. The mayor’s rival, Raci Bey, a man with a monopoly on wine production and owner of several olive oil companies, has allied himself with the equally violent Nazmi Bey, better known as Muhacir, and is also friendly with the speaker. Exactly what they are fighting about boils down, much of the time, to the grievances, petty and otherwise, which people with too little to do pursue in their quest for power.

The town itself, located in the Turkish mountains, is dominated by the remains of an ancient church at the top of a hill, and much of the action of the town over the generations has been related to the belief that a fabulous treasure is buried in the ruins there. Gradually, through flashbacks, the town’s characters and their roles in the action become clearer. The men control the life of the town, but they are divided into two groups, competing with each other for influence over the rest of the male population and using murder as a favorite – and very casual – weapon whenever one or another of the leaders becomes frustrated with the pace or direction of life. Mustafa Gurz, the corrupt mayor, allied with the violent Oleander Ramiz, becomes a friend, of sorts, with the speaker. The mayor’s rival, Raci Bey, a man with a monopoly on wine production and owner of several olive oil companies, has allied himself with the equally violent Nazmi Bey, better known as Muhacir, and is also friendly with the speaker. Exactly what they are fighting about boils down, much of the time, to the grievances, petty and otherwise, which people with too little to do pursue in their quest for power.

Some of these grievances are exacerbated by the women in the town, women who seem to have only one real talent or, it seems, interest, which they practice without restraint, and although the narrator seems reliable, he is new to town and has little knowledge of past history. In addition, he could challenge Casanova over his success with the women of the town. The author/speaker is obsessed with Zuhal, the long-time love and former lover of Mustafa, and as he lives totally in the moment, he does not recognize the concept of self-control in his own life. Zuhal continues to see Mustafa, and sometimes even says she loves Mustafa (when she is not saying that she does not love Mustafa), but she, too, returns to the narrator for comfort and loves him, too, sometimes talking of marrying him. She is not alone in sharing her passion with him. He also has erotic liaisons with Kamile Hanim, wife of Mustafa’s rival, Raci Bey, and though Kamile keeps her relationship with him secret, secrets in small towns sometimes leak. Since the speaker is often in bed with the lovers or ex-lovers of the leaders of both sides of the town’s murderous rivalry, it is only a matter of time before disaster strikes.

The speaker does not limit himself to just these two relationships, either, as passionate as they may seem. When he has time, he also visits his favorite prostitute, flirts with his housekeeper, and makes overt overtures toward her. The narrator himself observes that “Above ground, the men were engaged in disputes over land, power struggles and murder while women ruled the town with their urgent, uncontrollable sexual desires.” It is difficult to know if the speaker is being an ironic observer or if he is guilty of transference.

Long passages of self-analysis permeate the novel. The speaker himself has conversations with God, in which he compares the book he is writing with the one that God has written, daring to offer commentary on God’s book and on the future. He shares his many tweets to Zuhal with the reader, none of which seem to advance the action or the wandering plot. The many long conversations are not always pertinent. In short, though this book is described as “existentialist noir,” it lacks the terse, abbreviated dialogue, the fast action, and the carefully chosen detail which make noir novels, especially murder mysteries, so attractive. The foreshadowing throughout the novel keeps the reader looking for clues toward the future, but these are difficult to find in a novel as filled with personal, philosophical, and fantasy-filled commentary as this one. As the speaker’s flashbacks get closer to the situation which opens the novel, with the speaker awaiting some sort of final showdown following his murder of an unknown person, this reader, at least, became impatient with the pace of the novel. I had hoped it would provide more insight into the current, political climate in Turkey, even if that insight were limited to the tone and mood of the country. Instead, it seems so filled with distractions that the end result feels personalized, limited to the insights provided by a speaker/author who never really sees himself as part of a larger world in which he might have played a larger role if he had learned from a life of mistakes.

ALSO by Ahmet Altan: I WILL NEVER SEE THE WORLD AGAIN: The Memoir of an Imprisoned Writer

Photos: The author’s photo appears on https://bianet.org/

This rural Turkish vineyard, which might have been similar to the one owned by Raci Bey, is from http://www.alamy.com

An ancient church, which might have been similar to the one in this novel, with its secret treasure, is found on https://www.pinterest.com/

Kalamata olives on the tree: http://factsanddetails.com/