“It’s no longer any use begging for our rights by appealing to the regime, because it will not listen. But if a million Egyptians went out to the streets in protest or announced a general strike, if that happened, even once, the regime would immediately heed the people’s demands. Change, as far as it goes, is possible and imminent, but there is a price we have to pay for it.”—Alaa Al Aswany, in an article published by the opposition press in Egypt, a year before the revolution.

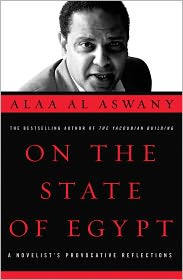

Alaa Al Aswany made his literary mark in 2002 when he wrote The Yacoubian Building, a novel set in one apartment building in central Cairo which illustrates virtually all the pressures within Egypt. It was “the best-selling novel in the Middle East for two years and the inspiration for the biggest budget movie ever produced in Egypt,” according to National Geographic. Now Al Aswany may become even more famous for a series of articles he wrote for the Egyptian opposition press from 2005 to the present. Always a promoter of human rights, which he believed were being trampled under the thirty-year rule of Hosni Mubarak, who also appeared to be preparing the country for a handover of power to his son Gamal, the author was a vocal supporter of those who began to challenge Mubarak publicly.

Alaa Al Aswany made his literary mark in 2002 when he wrote The Yacoubian Building, a novel set in one apartment building in central Cairo which illustrates virtually all the pressures within Egypt. It was “the best-selling novel in the Middle East for two years and the inspiration for the biggest budget movie ever produced in Egypt,” according to National Geographic. Now Al Aswany may become even more famous for a series of articles he wrote for the Egyptian opposition press from 2005 to the present. Always a promoter of human rights, which he believed were being trampled under the thirty-year rule of Hosni Mubarak, who also appeared to be preparing the country for a handover of power to his son Gamal, the author was a vocal supporter of those who began to challenge Mubarak publicly.

In a series of regular articles and columns that he wrote for an Egyptian audience, beginning in 2005, Al Aswany uses his literary power and popularity to try to reach all elements of Egyptian society, examining some of the issues which have separated Egyptians from each other, in an effort to show the importance of cooperation for the larger purpose of bringing about democracy in a country which has known only despotism, poverty, and corruption for decades. This book, published by the American University in Cairo Press, is a collection of these articles, concentrated primarily between the summer of 2009 and October, 2010. Explaining complex issues in language which all can understand, Al Aswany works toward a new beginning in Egypt. Few who read these articles now will doubt their impact on the populace, leading eventually to the demonstrations in Tahrir Square and the far-reaching revolution which took place between January 25, 2011 and February 11, 2011.

Tahrir Square

At the beginning of the book, Al Aswany ponders why Egypt has not had a revolution, despite the fact that “the level of corruption in government circles was unprecedented in the history of Egypt.” Among the many reasons he gives is the fact that repression was so all-pervasive that the populace, over two or three generations, had learned to submit to it. Though he regards this as cowardice, he understands the forces at work, and also recognizes that no organized system has existed to provide a way for the masses to rebel. Everyone has to work, if they are lucky enough to have jobs, and all have stayed alive by seeking individual solutions to the economic and personal crises they have faced. Many talented and educated people have left the country because they cannot get jobs if they do not know people in government who will hire them, and Egyptians have traditionally looked for compromises to avoid confrontation. The poor starve. More recently, Saudi oil money, with the blessing of the Mubarak regime, has led to the promotion of Wahhabi Islam within Egypt, a very conservative and fundamental interpretation of Islam which requires obeying the ruler (no matter how corrupt he may be).

Hosni Mubarak and son Gamal

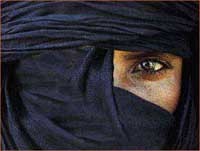

Many of the local television stations, owned by Saudis, continually feature uneducated “Islamic” preachers who represent “the worst of Islam” and appeal specifically to the poor, uneducated, and often illiterate in an effort to sway them to the extremely conservative Wahhabi point of view. As the author points out, these uneducated preachers earn huge salaries, while the dedicated Islamic preachers that he knew when he was growing up often had no money, ministering to the poor without recompense. Wahhabi wives and daughters are required to wear the niqab, as they do in Saudi Arabia. As recently as the 1970s, however, Egyptian women were treated as real human beings, not as sex objects, despite the fact that they wore modern clothing that revealed their arms and legs. Ironically, sexual harassment was much less common then than in the present. A recent ruling in Wahhabist Saudi Arabia has gone so far as to say that women with particularly beautiful eyes are a distraction that leads to men’s sexual excitement, and some groups have responded by now requiring women to wear niqabs that reveal only one eye. (See photo in photo credits.) For Mubarak, the more women who were taken out of the equation as human beings, the more secure the regime could feel.

Mohamed ElBaradei on his return to Egypt

Comprehensive examples of the Mubarak regime’s many long-standing economic and social abuses, too numerous to mention here, are cited in these articles, which cover just about every issue in Egyptian life, including religion. Of particular significance to the author is the fact that President Mubarak has not defended Egypt even when Egyptians have been detained and flogged in Saudi Arabia. Nor has he defended them when they have been tortured in Kuwait. Or when Egyptian soldiers were killed by Israelis on the Egyptian border. Or when Egyptians were attacked by Algerians during a World Cup soccer match. Young Egyptian men were detained while trying to greet Nobel Peace Prize winner Mohamed ElBaradei when he returned home from Austria, where he has been living. ElBaradei represented such a threat to the Mubarak government—and the succession of Gamal to the presidency—that he was escorted out of the airport via another gate to avoid the enthusiastic crowd that had gathered.

On January 25, 2011, when a call went out on the internet to demonstrate in Tahrir Square, about 200 – 300 people were expected. Over a million showed up. The revolution began. The author was there giving speeches for eighteen straight days, returning home only briefly during that time, because, he says over and over again, “Democracy is the solution.” An eye-opening and important book for everyone who cares about justice.

Photos, in order: The author’s photo appears on http://www.buecher.at

Tahrir Square during the revolution is from: http://en.wikipedia.org

Hosni and Gamal Mubarak at the World Economic Forum in 2009: http://www.georgeweyman.com

Mohamed ElBaradei, Nobel Prize Peace Prize winner in 2005, is the former head of the International Atomic Energy Commission. Often thought to be a possible successor to President Mubarak, he prefers to remain in private life. Here he returns to Egypt from his home in Vienna on January, 27, 2011, two days after the Tahrir Square demonstration began. http://kiaoragaza.wordpress.com

Mubarak’s exit as President was announced by his hand-picked vice president, Omar Suleiman, in a terse, one-sentence statement: ‘My fellow citizens,’ Suleiman said. ‘President Mubarak has decided to waive the office of president.’ The celebration is seen here: http://www.rferl.org

the office of president.’ The celebration is seen here: http://www.rferl.org

The one-eyed niqab, advocated by some Wahhabists may be seen here: http://doctorbulldog.wordpress.com

Also by Al Aswany: THE YACOUBIAN BUILDING