“Today, in 1865, in the twenty-eighth year of Her Majesty Queen Victoria’s reign, human understanding of nature and society was surely nearing completion. Economic science showed the inexorable law by which wealth was generated by the poor and flowed to the rich. Social science revealed the inevitability that a sizeable segment of the poor would sink towards crime and depravity. Statistical science showed the precise extent to which this would happen.”

Lovers of Victorian Gothic mysteries will have loads of fun with this one, quite different in tone from the norm, and lovers of literary fiction will admire the author’s ability to describe and bring the period to life while also conveying important sociological and religious issues. Written by Alastair Sim, great-nephew of the famed actor of the same name, while he was still a student at the University of Glasgow, the novel takes the Victorian police procedural in new directions. Inspector Archibald Allerdyce, an emotionally damaged man who no longer believes in God, and Sergeant Hector McGillivray, even more damaged from his army experiences during the colonial rebellion in India and the Crimean War, have been ordered by the highest levels of government to solve the disappearance of William Bothwell-Scott, the Duke of Dornoch, wealthiest man in Scotland.

Lovers of Victorian Gothic mysteries will have loads of fun with this one, quite different in tone from the norm, and lovers of literary fiction will admire the author’s ability to describe and bring the period to life while also conveying important sociological and religious issues. Written by Alastair Sim, great-nephew of the famed actor of the same name, while he was still a student at the University of Glasgow, the novel takes the Victorian police procedural in new directions. Inspector Archibald Allerdyce, an emotionally damaged man who no longer believes in God, and Sergeant Hector McGillivray, even more damaged from his army experiences during the colonial rebellion in India and the Crimean War, have been ordered by the highest levels of government to solve the disappearance of William Bothwell-Scott, the Duke of Dornoch, wealthiest man in Scotland.

The Duke has amassed a ten thousand-acre estate by having his thugs clear the land of long-time poor residents, also demolishing a small village near the coast which interfered with his view. Just as cavalierly, the Duke has drastically cut the wages of the workers in his five mines. When he is discovered shot dead and pitched into a well, formerly a mine, on his estate, the number of potential suspects is so long that the government decides, for political reasons, to announce his death as accidental. His brother Frederick becomes the eighth Duke or Dornoch, not an improvement, as Frederick, a drunk and a bully, has no conscience at all. “I’m sorry for William,” he says at William’s funeral, “but it’s an upturn in my own fortunes.”

Allerdyce’s investigation of William’s death takes him into the lower depths of the city, described in terms that “out-Dickens” Dickens—houses of prostitution; bars where the Duke, known to them as Willie Burns, can indulge his desires for young men; gambling dens and dog pits where ratters vie to kill fifty brown rats in five minutes—places so dangerous that Allerdyce needs two men to watch his back. Despite the information that Allerdyce and McGillivray discover, the police powers-that-be, tied to the government, insist that the murderer must be the head of the Scottish mines or the foreman who cleared the Duke’s lands. True justice is unimportant—just the appearance of justice, the quicker the better. Eventually, in true gothic tradition, several other murders occur, innocent people are jailed and quickly subjected to summary trials, an illegitimate child threatens the succession to the estate, coincidences resolve a number of plot issues, and complicated love stories unfold.

As one might expect from the  title, the socio-religious changes in Victorian society can be seen in the conflicts faced by some of the main characters here, especially Allerdyce. Darwin’s Origin of the Species, published in 1859, has challenged the traditional church beliefs in Separate Creation and the Chain of Being, with man at the top of the chain and rich men at the very top. Spiritualism, a new movement, is becoming popular. Trade unions are beginning to form, and communism, also new, is gaining followers among the poor. Colonial wars, and the country’s involvement in the Crimea, in which the poor have been used as cannon fodder by their aristocratic officers, have further exacerbated class divisions. Allerdyce, despite his agnosticism and awareness of the social inequities, still sees the world in black and white, however: The law is the law, and no compromises are possible, even if the results make no sense on a grander scale. “Sometimes,” he says grandly, “your duty to the law doesn’t seem to do justice to the people you encounter,” but he does his duty anyway.

title, the socio-religious changes in Victorian society can be seen in the conflicts faced by some of the main characters here, especially Allerdyce. Darwin’s Origin of the Species, published in 1859, has challenged the traditional church beliefs in Separate Creation and the Chain of Being, with man at the top of the chain and rich men at the very top. Spiritualism, a new movement, is becoming popular. Trade unions are beginning to form, and communism, also new, is gaining followers among the poor. Colonial wars, and the country’s involvement in the Crimea, in which the poor have been used as cannon fodder by their aristocratic officers, have further exacerbated class divisions. Allerdyce, despite his agnosticism and awareness of the social inequities, still sees the world in black and white, however: The law is the law, and no compromises are possible, even if the results make no sense on a grander scale. “Sometimes,” he says grandly, “your duty to the law doesn’t seem to do justice to the people you encounter,” but he does his duty anyway.

In the second half of the book, deliberate religious symbols and parallels appear, causing the mystery to veer off in unexpected directions. Patrick Slater is seen as a Christ figure, living in the wilderness and doing good deeds, Allerdyce is declared to be a Judas by someone he wants to help, Easter images describe someone who “rises to a better life,” and a character on trial is asked if he believes in the Bible as God’s perfect word for man, his answer determining his fate.

The author’s brilliant imagery makes the setting and atmosphere come alive, while the complexities of the plot reveal the author’s comprehensive vision of society. The characters, with the exception of Allerdyce, tend to be stereotypes, in the fashion of typical Victorian Gothic novels. Where this novel differs from most other novels of its genre is in its mood—the customary happy ending, with all details resolved, is omitted. Instead, the reader is left to ponder the social and religious issues that the author has raised. Though his primary purpose is not completely clear and the themes, introduced and developed late, are sometimes fuzzy, the author’s vibrant depiction of a fragmented, class-based society with its equally class-based system of justice is absorbing and memorable.

Photos, in order: The author’s photo and announcement as recently appointed director of Universities Scotland are here: www.timeshighereducation.co.uk

Skibo Castle in Dornoch may have been a model for the estate of the Duke of Dornoch. Skibo was restored as the home of Andrew Carnegie in 1898 and remained in his family until 1982. The Duke of Dornoch’s castle was described as having 10,000 acres in 1865; Skibo has 7,500 acres now. Photo by Heather Swinton: http://travel.webshots.com

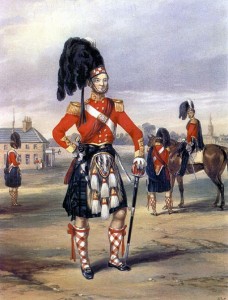

Sgt. Hector McGillivray’s younger brother was a member of the 93rd Highlanders and died in the Crimea, an event for which McGillivray still blames Brig. Frederick Bothwell-Scott. The officers of that regiment (dressed as in the attached drawing) were part of the “Thin Red Line” and The Charge of the Light Brigade: www.britishbattles.com .