Note: This novel is WINNER of the Commonwealth Writers Prize for 2011.

“Sometimes I think this country is like a garden. Only it is a garden where somebody has pulled out all the flowers and trees, and the birds and insects have all left, everything of beauty. Instead the weeds and poisonous plants have taken over.”

Set primarily in the late 1990s in Sierra Leone, a time in which a brutal Civil War is being waged and over fifty thousand people killed, this novel comes as a surprise. Telling two tales of love in two different generations, the author is mightily challenged to be true to her setting and time periods while also allowing the love stories to develop naturally within this fraught environment. She accomplishes this, largely, by referring to the war only obliquely for most of the novel, with flashbacks by individual speakers providing details of the war and explaining how the memories of war have affected the behavior of characters whom the reader has come to know. A flash-forward which takes place in 2003, after the end of the war, occurs at the end to reconcile elements of the plot and themes.

Set primarily in the late 1990s in Sierra Leone, a time in which a brutal Civil War is being waged and over fifty thousand people killed, this novel comes as a surprise. Telling two tales of love in two different generations, the author is mightily challenged to be true to her setting and time periods while also allowing the love stories to develop naturally within this fraught environment. She accomplishes this, largely, by referring to the war only obliquely for most of the novel, with flashbacks by individual speakers providing details of the war and explaining how the memories of war have affected the behavior of characters whom the reader has come to know. A flash-forward which takes place in 2003, after the end of the war, occurs at the end to reconcile elements of the plot and themes.

As the novel opens, Elias Cole, a former professor and Dean of the university in Freetown, is now an elderly hospital patient, dying from pulmonary fibrosis, a slow disease which robs him of his breath. Tended by his own servant, Babagaleh, for much of the day, he is a patient of Adrian Lockheart, a British psychiatrist who has left his wife and daughter behind in England while he works for six months in the hospital near the university. Adrian quickly discovers that the dying Elias has memories that he is impelled to share about his life in the 1970s, many of these involving Saffia, the wife of Julius Kamara, a young professor. Old-fashioned story-telling conveys episodes from Elias’s memories of his much younger life, and the author emphasizes from the beginning that it is with these three characters that the entire story really begins—Elias Cole, Julius Kamara, and Saffia. “Perhaps we three would each put the beginning in a different place, like blindfolded players trying to pin the tail on a donkey,” Elias notes. But just as there are three different beginnings, so, too, will there be “three different endings, one for each of us.”

Babagaleh, for much of the day, he is a patient of Adrian Lockheart, a British psychiatrist who has left his wife and daughter behind in England while he works for six months in the hospital near the university. Adrian quickly discovers that the dying Elias has memories that he is impelled to share about his life in the 1970s, many of these involving Saffia, the wife of Julius Kamara, a young professor. Old-fashioned story-telling conveys episodes from Elias’s memories of his much younger life, and the author emphasizes from the beginning that it is with these three characters that the entire story really begins—Elias Cole, Julius Kamara, and Saffia. “Perhaps we three would each put the beginning in a different place, like blindfolded players trying to pin the tail on a donkey,” Elias notes. But just as there are three different beginnings, so, too, will there be “three different endings, one for each of us.”

A parallel narrative, with different main characters, takes place sometime around 2001, near the end of the war, with flashbacks to events of the late 1990s. Kai Mansaray, a brilliant surgeon who lives a significant distance from the hospital, sometimes “crashes” for a few hours in Adrian’s apartment, and the two become friends. Kai is single but has family, including a young nephew who adores him. These relatives live outside the city. On one trip to visit them, Kai brings Adrian, whose life is changed dramatically by an event which happens when he recognizes a former patient who has left the hospital without being fully treated. When the war stories which have dramatically affected this patient’s life—and that of Kai’s family—are revealed, along with the lives of those who have had to spend two years or more in refugee camps, the brutality of the attacking soldiers is almost beyond belief. As Kai says, “[We are] a nation devouring itself.”

A parallel narrative, with different main characters, takes place sometime around 2001, near the end of the war, with flashbacks to events of the late 1990s. Kai Mansaray, a brilliant surgeon who lives a significant distance from the hospital, sometimes “crashes” for a few hours in Adrian’s apartment, and the two become friends. Kai is single but has family, including a young nephew who adores him. These relatives live outside the city. On one trip to visit them, Kai brings Adrian, whose life is changed dramatically by an event which happens when he recognizes a former patient who has left the hospital without being fully treated. When the war stories which have dramatically affected this patient’s life—and that of Kai’s family—are revealed, along with the lives of those who have had to spend two years or more in refugee camps, the brutality of the attacking soldiers is almost beyond belief. As Kai says, “[We are] a nation devouring itself.”

Refugees walking to Guinea, carrying everything they can

There are no “good guys” here—the two sides are equally brutal. The army is relentless in trying to root out the rebels and those thought to support them, and will do anything to prevent them from gaining a foothold. The rebels are equally determined to eliminate those they believe to be corrupt, which seems to include most of the “advantaged” population of the country. Soon Adrian becomes more intimate with the horrors, as Elias reveals some of the events which occurred in the years leading up to this civil war. Adrian himself becomes more familiar with the stories of his mental patients (almost all of whom have some form of post-traumatic stress disorder, if not worse), and he falls desperately in love with an African woman. The last chapter, which takes place in 2003, brings the parallel love stories up to date and provides surprises.

Diamond miners

The author’s descriptions of the war relate to events specific to individual characters, but they are generalized in terms of motivations and settings, and the author never really goes into the kind of detail which would distinguish this war from those of other African countries, including neighboring Liberia, under Charles Taylor, who is said to have provided immense support to the rebels. Nor does she mention the issue of Sierra Leone’s “blood diamonds,” which are said to have financed the rebel movement, both in Sierra Leone and in Liberia. No names of real historical characters surface here at all, but whether this may have been to keep the emphasis on the fictional love story remains unclear. I often found myself wondering what the author’s overall purpose was: A love story in the midst of war? A war story and its effects on lovers? Or a more fully developed examination of the overall power of love and its loss on a universal scale? The author seems to be aiming for all of these with the novel’s length but not quite reaching her thematic goals, not quite integrating her many episodes and her large cast of characters with an over-arching structure.

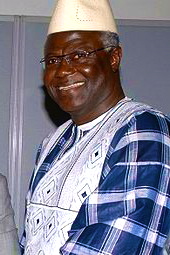

Elected President in 2007, Ernest Bai Koroma has continued and expanded the reforms of his predecessor

The parallel narratives are often very effective, but there was extraneous detail, and I found myself wishing that Forna and her editor had tightened the narrative by cutting a hundred pages. As the war stories intrude more and more near the end of the novel, I wondered why the author waited so long to include them: Drawing out the suspense about the characters’ backgrounds does not seem to benefit this novel which has so many characters, all with different stories to tell. Ultimately, the characters themselves may not be completely reliable. As one character says, “People are blotting out what happened, fiddling with the truth, creating their own version of events to fill in the blanks. A version of the truth which puts them in a good light, that wipes out whatever they did or failed to do and makes certain none of them will be blamed.” Certainly, that is the case with the love stories here, as much as it is with the history.

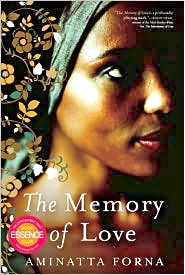

Photos, in order: The author’s photo comes from http://www.ft.com.

The map of Sierra Leone appears on http://www.yourchildlearns.com.

Refugees walking to Guinea, carrying everything they can, are seen on http://www.sierra-leone.org, a site which also bears witness to the atrocities.

Diamond miners in Sierra Leone are from http://en.wikipedia.org

Elected President in 2007, Ernest Bai Koroma has continued and expanded the reforms of his predecessor, enacted a law which requires elected officials to declare all their assets every year, and put in place strong laws against drug trafficking, even allowing for the extradition of drug traffickers to other countries. He is one of the few African heads of state to have condemned Robert Mugabe of Zimbabwe, and he has stated repeatedly that he wants his country to be run like a business, enlisting the aid of the British to help make it so. http://en.wikipedia.org