“If it is God’s will that opium be used as an instrument to open China to his teachings, then so be it. For myself, I confess I see no reason why any Englishman should abet the Manchu tyrant in depriving the people of China of this miraculous substance.”

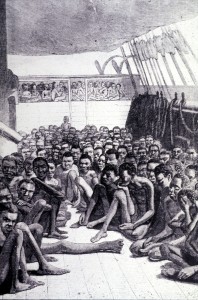

When the Ibi s, a “blackbirder” leaves Calcutta and sets out across the Bay of Bengal, carrying “indentured migrants,” many of whom will become the equivalent of slaves, the seas darken and become stormy. As the ship tosses and conditions deteriorate, the ship soon becomes a microcosm for life on land, full of tumult and unexpected twists of fate, and each person’s heart is laid bare. Everybody aboard is escaping from something, so anxious to put their problems behind them that they see no choice but to submit to the atrocious living conditions and sometimes sadistic overseers aboard the Ibis. Life aboard the ship is as stratified and as subject to both cruelty and courage as the occupants have experienced on land, but as the ship heads for new ports in foreign lands, its occupants still see it as the only possible escape from their past and its problems.

s, a “blackbirder” leaves Calcutta and sets out across the Bay of Bengal, carrying “indentured migrants,” many of whom will become the equivalent of slaves, the seas darken and become stormy. As the ship tosses and conditions deteriorate, the ship soon becomes a microcosm for life on land, full of tumult and unexpected twists of fate, and each person’s heart is laid bare. Everybody aboard is escaping from something, so anxious to put their problems behind them that they see no choice but to submit to the atrocious living conditions and sometimes sadistic overseers aboard the Ibis. Life aboard the ship is as stratified and as subject to both cruelty and courage as the occupants have experienced on land, but as the ship heads for new ports in foreign lands, its occupants still see it as the only possible escape from their past and its problems.

Set in India in 1838, at the outset of the three-year Opium War between the British and the Chinese, this epic novel follows several characters from different levels of society, who become united through their personal lives aboard the ship and, more generally, through their connections to the opium and slave trades. Deeti Singh, married as a young teenager to a man whose dependence on opium makes him an inadequate husband and provider, is forced to work on the family’s opium field outside Ghazipur by herself, though she fears her sadistic brother-in-law. When she has no options left that make sense to her, she escapes, eventually joining the migrants aboard the Ibis.

The Ibis, owned by Burnham Brothers, carries as one of its mates a young sailor from Baltimore, Zachary Reid, who has left America because his status as an octoroon has led to constant harassment by other American sailors. These two characters, Deeti and Reid, see life as it is, recognizing all its cruelty but also seeing its potential, and their clear-eyed observations of life around them vividly convey their cultures and the roles open to them.

At the opposite end of the scale from Deeti and Reid, is Benjamin Burnham, who owns the Ibis and engages in the opium trade, which his family controls in Ghazipur, fifty miles east of Benares. Since the slave trade has been officially ended, Burnham has kept the Ibis intact and simply switched to the transport of exiled prisoners and coolies. Though Burnham is the son of a Liverpool tradesman, his willingness to finance and manage these exploitative trades has led to enormous wealth and a lavish lifestyle impossible for him in England. Among his acquaintances is Raja Neel Rattan Halder, the zemindar of Raskali, whose life epitomizes the unimaginable opulence that upper caste Brahmins assume is their right by birth. Never questioning his high caste existence, Neel has paid little attention to his dwindling resources, and he has now accumulated debts.

Ghosh de picts the lives of these characters and their acquaintances in extravagant and thoroughly researched detail, bringing to life Deeti’s misery, the expectations for her within her husband’s family, the customs which she must honor, and the life which her six-year-old daughter must expect (including marriage within three or four years). Zachary Reid, aboard the Ibis, becomes the protégé of Serang Ali, the leader of the lascars, those native seamen who perform the hard manual labor aboard ships. Though Reid’s own background is not so different from that of the lascars, he is a foreigner, a man who has no known caste within Indian society, and Serang Ali treats him as a superior to the lascars, all of whom are either low-caste or caste-less. With the support of the lascars and Serang Ali, Zachary Reid has the potential to progress to officer status, something impossible for him at home, and as he shares his thoughts about his own life, he is also commenting on the human condition in general.

picts the lives of these characters and their acquaintances in extravagant and thoroughly researched detail, bringing to life Deeti’s misery, the expectations for her within her husband’s family, the customs which she must honor, and the life which her six-year-old daughter must expect (including marriage within three or four years). Zachary Reid, aboard the Ibis, becomes the protégé of Serang Ali, the leader of the lascars, those native seamen who perform the hard manual labor aboard ships. Though Reid’s own background is not so different from that of the lascars, he is a foreigner, a man who has no known caste within Indian society, and Serang Ali treats him as a superior to the lascars, all of whom are either low-caste or caste-less. With the support of the lascars and Serang Ali, Zachary Reid has the potential to progress to officer status, something impossible for him at home, and as he shares his thoughts about his own life, he is also commenting on the human condition in general.

Filled with local patois, in which most of the meanings are clear from context (though the book contains a helpful glossary), Ghosh creates a rich and colorful atmosphere. He fully describes buildings, their contents, bath facilities, dining customs, religious practices, the inside of a slave ship, and even the importance of omens, but he never forgets his obligation as a story-teller, continuously presenting one highly dramatic moment after another. Stories of piracy and cruelty, often growing out of the opium trade, exist side by side with more personal stories of love and nobility, and as the characters grow and make decisions, their actions grow directly from their experiences. Episodes of humor live side by side with episodes of terror.

The first book in a projected “Ibis trilogy,” this historical novel pulses with life, filled with details of everyday existence and the cultures of the characters, which make the actions of its characters understandable. A monument to the desire for a better life and the willingness of people to take chances in order to attain it, the novel is also a vibrant and textured depiction of the historical moment—at the time when China declared it would prohibit the importation of opium, which was decimating its addicted citizens. British traders, who had been forcing Indian laborers to turn over their fields to the growing of poppies, were willing to declare war to save their profits, despite the fact that the British government did not know that the traders were about to declare war.

As the novel comes to a satisfying close, Ghosh leaves several doors open suggesting the direction he will take with this novel’s sequel, which will undoubtedly continue into the Opium War itself with many of the same characters. On the short list of nominations for the Man Booker Prize for 2008, this rich and exciting historical epic has something for everyone.

Notes: Also reviewed here: Amitav Ghosh’s THE GLASS PALACE

The author’s photo appears on http://www.mahamediaonline.com

Image of the Slave Deck of the Bark “Wildfire” (1860), from the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division (LC-USZ62-41678). For many more drawings and prints, see http://hitchcock.itc.virginia.edu

The painting of an Opium War battle between the British and Chinese (by an unnamed artist) appears on http://theformofmoney.blogharbor.com