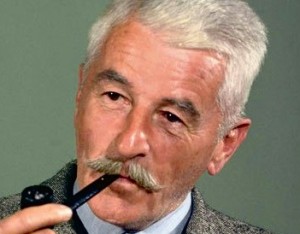

As [William] Faulkner’s daughter, Jill, wrote, “Pappy was getting ready to start on one of these bouts. I went to him and said, ‘Please don’t start drinking.’ And he was already well on his way, and he turned to me and said, ‘You know, no one remembers Shakespeare’s child.’ ”

In his brief biographies of approximately forty “literary rogues,” from the Marquis de Sade (1740 – 1814) to James Frey (1969 – ), author Andrew Shaffer enumerates the many addictions of each author – virtually all of them associated with alcohol and drugs and/or their frequent carryover into sexual obsession. In fact, if one were to regard these authors as typical of the period, one might conclude that, until the last couple of decades, addictions of all kinds were practically mandatory for successful writers. How else, these authors seemed to think, could a writer tap into his creativity and release his “inner story-teller” with all its attendant angels or demons?

In his brief biographies of approximately forty “literary rogues,” from the Marquis de Sade (1740 – 1814) to James Frey (1969 – ), author Andrew Shaffer enumerates the many addictions of each author – virtually all of them associated with alcohol and drugs and/or their frequent carryover into sexual obsession. In fact, if one were to regard these authors as typical of the period, one might conclude that, until the last couple of decades, addictions of all kinds were practically mandatory for successful writers. How else, these authors seemed to think, could a writer tap into his creativity and release his “inner story-teller” with all its attendant angels or demons?

While there was plenty of addiction to go around among authors over the years, these authors probably are not the norm, the non-addicted simply not being scandalous enough to have been included in a book of this type. It is significant, too, and reflective of the role of women writers during the times about which Shaffer writes, that of the approximately forty authors Shaffer describes, only six women receive more than a sentence of recognition: Mary Shelley; Zelda Fitzgerald, Edna St. Vincent Millay, and Dorothy Parker, who were all contemporaries; Anne Sexton; and Elizabeth Wurtzel. While these women could hold their own with the literary male alcoholics and addicts of their times, they seem to be a small percentage of the relatively small number of women who succeeded as authors during this period.

While there was plenty of addiction to go around among authors over the years, these authors probably are not the norm, the non-addicted simply not being scandalous enough to have been included in a book of this type. It is significant, too, and reflective of the role of women writers during the times about which Shaffer writes, that of the approximately forty authors Shaffer describes, only six women receive more than a sentence of recognition: Mary Shelley; Zelda Fitzgerald, Edna St. Vincent Millay, and Dorothy Parker, who were all contemporaries; Anne Sexton; and Elizabeth Wurtzel. While these women could hold their own with the literary male alcoholics and addicts of their times, they seem to be a small percentage of the relatively small number of women who succeeded as authors during this period.

The first half of Shaffer’s book deals with European authors, beginning with the Marquis de Sade, the source of the word “sadism.” Sade was a sick man who spent the last part of his life in prison after his mother-in-law turned him in to authorities for serious crimes ranging from prostitution to attempted murder by poisoning. Coleridge, as we all know, was an opium addict; Robert Burns was a hopeless alcoholic; and Thomas De Quincey was addicted to daily laudanum (mentioned in a chapter which also refers briefly to Louisa May Alcott’s addiction to laudanum). The English Romantics, including Lord Byron (who may have impregnated his half-sister); Percy Bysshe Shelley; and Mary Shelley, author of Frankenstein, were hypersensitive, uninhibited, and prone to suicide. Poe, an American who married his thirteen-year-old cousin, used drink and drugs to escape his “torturing memories,” and he was also a gambler, though he was supposedly never addicted to laudanum.

The first half of Shaffer’s book deals with European authors, beginning with the Marquis de Sade, the source of the word “sadism.” Sade was a sick man who spent the last part of his life in prison after his mother-in-law turned him in to authorities for serious crimes ranging from prostitution to attempted murder by poisoning. Coleridge, as we all know, was an opium addict; Robert Burns was a hopeless alcoholic; and Thomas De Quincey was addicted to daily laudanum (mentioned in a chapter which also refers briefly to Louisa May Alcott’s addiction to laudanum). The English Romantics, including Lord Byron (who may have impregnated his half-sister); Percy Bysshe Shelley; and Mary Shelley, author of Frankenstein, were hypersensitive, uninhibited, and prone to suicide. Poe, an American who married his thirteen-year-old cousin, used drink and drugs to escape his “torturing memories,” and he was also a gambler, though he was supposedly never addicted to laudanum.

Baudelaire, Rimbaud, and Verlaine added absinthe to the French drug culture of which they were part. Oscar Wilde, back in England, claimed to be “the high priest of decadence,” while Ernest Dowson, claimed to be “as decadent as one could get without actually being French.”

Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald

With the Lost Generation, however, the novel begins its focus on authors from the United States, including, first, Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald, who moved back and forth between the US and Europe, and whom Dorothy Parker found “too ostentatious for words, their behavior calculated to shock.” Despite this, Parker managed to have an affair with Fitzgerald. He died at the age of forty-four, though he “died inside himself at around the age of thirty or thirty-five, and his creative powers died somewhat later.”

Dorothy Parker

Dorothy Parker, Edna St. Vincent Millay, Robert Benchley, Robert Sherwood and several other members of the Algonquin Round Table, were alcoholics, with Parker addicted to Scotch and also to cigarettes (smoking three or four packs a day). Of all the Round Table authors, however, it is Parker whose “literary celebrity has stood the test of time.”

Ernest Hemingway’s alcoholism did not keep him from winning the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1954, but it probably did contribute to his paranoia. Even while he was retired in Cuba, he “saw FBI agents everywhere,” and it was only after his death that his publisher discovered that J. Edgar Hoover actually did have him under surveillance for his activities in Cuba, and that his hospital room, where he underwent eleven electroshock treatments in 1960, probably was bugged. Faulkner, also an alcoholic, once walked the halls of a New York City hotel nude, and was known to average twenty-three martinis a day. He, too, won the Nobel Prize for Literature (in 1949), despite his alcoholism.

William Faulkner

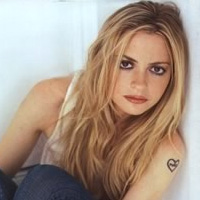

Jack Kerouac, William Burroughs, Alan Ginsburg, John Berryman, Anne Sexton, Ken Kesey, Truman Capote, Norman Mailer, Hunter S. Thompson, John Cheever, Raymond Carver, Jay McInerney, Bret Easton Ellis, Elizabeth Wurtzel, and James Frey bring the list of “wayward authors” up to date, their drugs of choice ranging from alcohol to LSD, mescaline, and cocaine. It is in this final section that the author introduces ideas and observations which are different from the stories we already know. Beginning in the 1980s, authors began to lose their influence on popular culture – there were many other ways, many of them electronic and/or cinematic, through which those with something to say could find an audience. In addition, writers like Wurtzel had sought and received help from the medical profession for their depression, something that writers had avoided in the past. As Wurtzel says, however, “The question of whether the ‘real you’ is the person on lithium or the person on illegal drugs doesn’t matter…What matters is whether you function or not. We don’t know that the medication isn’t helping you become the real you.”

Elizabeth Wurtzel, now a practicing attorney

Joyce Carol Oates once pointed out that “nobody tells anecdotes about the quiet people who just do their work,” and the author himself observes that if you “Take a look at any list of the top hundred novels of all time…you’ll see plenty of quiet, sober names…As memoirists have known for years, the more [messed] up your life, the more compelling your life story.” Here some of the “wayward authors” get more of the attention they obviously sought, but the fact that they are here, and known to the reader at all, attests to the fact that they somehow managed to achieve fame, if not respect, despite their various addictions and problems. For them the pen was mightier than the weakness.

Photos, in order: The author’s photo by Sally Ryan may be found at http://www.nytimes.com

Mary Shelley’s portrait appears on http://www.underthegoldenappletree.com

Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald are from http://www.thelmagazine.com

Dorothy Parker’s photo is from http://behindthecurtaincincy.com

The William Faulkner photo may be found on http://jthorsson.com

Elizabeth Wurtzel’s portrait appears on http://www.thesecretlanguage.com

ARC: Harper Perennial