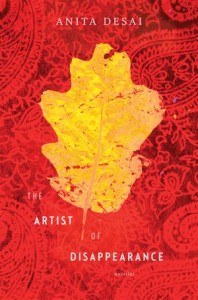

Always an astute observer and subtle writer about human nature, Anita Desai is at her best here, creating a group of three novellas, each of which reveals the interplay between a main character dealing with universal issues and a second character (sometimes more) who sees the world and its values quite differently. The result is a book that feels almost sacred, in the sense that it is morally serious and filled with thematically weighty stories. The themes in these stories, however, are often subtle – revealing unspoken lessons on many levels – neither moralistic, obvious, nor absolute. In all the novellas, the main character, approaching the end of a problem, might well conclude that what s/he wants, “[is] dead, a dead loss, a waste of time,” a statement actually made in the final novella, “The Artist of Disappearance.” For the involved reader, however, “the loss” is not the point. What the reader gains is a new appreciation of the small joys and great sorrows which fill the lives of plain people in rural India trying to find beauty and, perhaps, the fulfillment of dreams within

Always an astute observer and subtle writer about human nature, Anita Desai is at her best here, creating a group of three novellas, each of which reveals the interplay between a main character dealing with universal issues and a second character (sometimes more) who sees the world and its values quite differently. The result is a book that feels almost sacred, in the sense that it is morally serious and filled with thematically weighty stories. The themes in these stories, however, are often subtle – revealing unspoken lessons on many levels – neither moralistic, obvious, nor absolute. In all the novellas, the main character, approaching the end of a problem, might well conclude that what s/he wants, “[is] dead, a dead loss, a waste of time,” a statement actually made in the final novella, “The Artist of Disappearance.” For the involved reader, however, “the loss” is not the point. What the reader gains is a new appreciation of the small joys and great sorrows which fill the lives of plain people in rural India trying to find beauty and, perhaps, the fulfillment of dreams within an overwhelming reality. All the characters want to preserve something beautiful and important to them, but all must persevere against forces which consider their own goals to be more important than those of the people with whom they are dealing. Ultimately, each main character becomes an “artist of disappearance,” either physically, emotionally, or spiritually.

an overwhelming reality. All the characters want to preserve something beautiful and important to them, but all must persevere against forces which consider their own goals to be more important than those of the people with whom they are dealing. Ultimately, each main character becomes an “artist of disappearance,” either physically, emotionally, or spiritually.

In “The Museum of Final Journeys,” an old man from the remote countryside travels to the residence of a new county official begging for help.

“Sir, please help us. Please appeal on our behalf to the government, the sarkar, to take the museum from us into its custody and provide for us, and for this last gift we were sent. I am ashamed, sir…Forgive me for begging you”

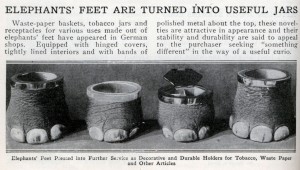

The old man has been working for almost all of his life for the same family, but they are all either dead or missing now. The family’s only son, educated abroad, has traveled the world, collecting objects which he sends to his mother for her enjoyment. After her death, the objects continue to arrive, and the old servant and his assistant, create a house-museum for these “obsolescent” objects—stuffed animals and birds, miniature paintings from Persia and the Mughal Empire, and antique weapons of war, among other things. The final gift from the son is the one which the old man loves most, but it requires a great deal of maintenance, and he wants the government official to accept the other valuable museum objects as a gift to the country and allow him to preserve this one final gift, which has “provided him with the purpose of his life.” The servant and the official live in different worlds and have difficulties communicating.

The old man has been working for almost all of his life for the same family, but they are all either dead or missing now. The family’s only son, educated abroad, has traveled the world, collecting objects which he sends to his mother for her enjoyment. After her death, the objects continue to arrive, and the old servant and his assistant, create a house-museum for these “obsolescent” objects—stuffed animals and birds, miniature paintings from Persia and the Mughal Empire, and antique weapons of war, among other things. The final gift from the son is the one which the old man loves most, but it requires a great deal of maintenance, and he wants the government official to accept the other valuable museum objects as a gift to the country and allow him to preserve this one final gift, which has “provided him with the purpose of his life.” The servant and the official live in different worlds and have difficulties communicating.

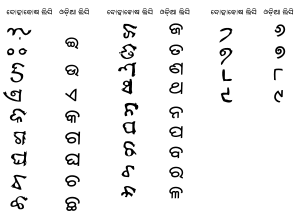

“Translator Translated” is quite a different story. Meek little Prema Joshi returns for her high school Founder’s Day and meets Tara, who had been the brightest and most popular student at the school. Prema, now teaching the work of authors like Jane Austen and George Eliot, has been studying Oriya, her mother’s language, and she is particularly fond of the work of Suvarna Devi, unknown beyond the hillside village where she lives. Tara, a publisher of the work of previously unknown female writers, asks Prema to translate Suvarna Devi’s first work, the answer to Prema Joshi’s prayers. As a result of this project, every aspect of Prema’s life changes, and as she translates Suvarna Devi’s work, “[It is] as if we were sisters – or even as if we were one, two compatible halves of one writer.” The second work by Devi is disappointing in its triteness and its clichés, however.

“A faithful translation would clearly make for a flat, boring read. I saw that what was needed was for me to be inventive, take things into my own hands and create a style for the book”

The results are predictable, and the effects on Prema Joshi’s modest life are significant.

The results are predictable, and the effects on Prema Joshi’s modest life are significant.

The final novella, “The Artist of Disappearance,” tells the story of Ravi, a boy whose wealthy parents ignored him. Living for the summers when they left to travel, he remained at home exploring the countryside. As the novella opens, he is an adult, living in the burned remains of the family home at the top of a hill. As Ravi’s story evolves, his sensitivity to the world around him becomes clear, and his understanding of aesthetics regarding the natural world in all its glories is particularly sophisticated.

“Outdoors was freedom. Outdoors was the life to which he chose to belong – the life of the crickets springing out of the grass, the birds wheeling hundreds of feet below the valley or soaring upwards above the mountains, and the animals invisible in the undergrowth, giving themselves away by an occasional rustle or eruption of cries or flurried calls…One had only to be silent, aware, observe and perceive – and this was Ravi’s one talent as far as anyone could see.”

Ravi has been creating a hidden garden which represents the essence of beauty for him, as long as it remains private.

Ravi has been creating a hidden garden which represents the essence of beauty for him, as long as it remains private.

The importance of beauty and the problem of how (and whether) to save it for future generations permeate this collection. Who should determine its value? How much beauty should be personal, local? Is there a role for the sensitive artist in Indian society today? As Desai explores these ideas in prose of almost crystalline purity and concision, her sensitivity to the idea of “less is more” prevails. She never tells too much, leaving the reader to draw from each story what is personally meaningful. One of my favorite books of the year.

Photos, in order: The author’s photo is from http://www.outlookindia.com

The display of objects made from elephant feet, like the umbrella stand in the “museum,” is from 1924: http://blog.modernmechanix.com

A miniature painting from India, reminiscent of the ones in the “museum”: http://www.craftsinindia.com

The Oriya “alphabet” may be found here: http://en.wikipedia.org

Ravi lives in Mussorie in the northernmost area of India, northeast of Delhi. This beautiful scene is found on http://www.dehraduntravelguide.com